Joshi Festival na tribo Kalash no Paquistão, 14 de maio de 2011. Crédito:Shutterstock/Maharani afifah

Abro os olhos ao som de uma voz enquanto a aeronave bimotor a hélice da Pakistan Airlines voa pela cordilheira Hindu Kush, a oeste do poderoso Himalaia. Estamos navegando a 27.000 pés, mas as montanhas ao nosso redor parecem preocupantemente próximas e a turbulência me acordou durante uma viagem de 22 horas ao lugar mais remoto do Paquistão - os vales Kalash da região de Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.

À minha esquerda, uma passageira perturbada está orando em silêncio. À minha direita está meu guia, tradutor e amigo Taleem Khan, membro da tribo politeísta Kalash, que conta com cerca de 3.500 pessoas. Este era o homem que estava falando comigo quando eu estava acordando. Ele se inclina novamente e pergunta, desta vez em inglês:"Bom dia, irmão. Você está bem?"

"Prúst," (estou bem) respondo, à medida que me torno mais consciente do que me cerca.

Não parece que o avião está descendo; em vez disso, parece que o chão está vindo ao nosso encontro. E depois que o avião atingiu a pista e os passageiros desembarcaram, o chefe da Delegacia de Chitral está lá para nos cumprimentar. Temos uma escolta policial para nossa proteção (quatro policiais operando em dois turnos), pois há ameaças muito reais a pesquisadores e jornalistas nesta parte do mundo.

Só então podemos embarcar na segunda etapa de nossa viagem:um passeio de jipe de duas horas até os vales de Kalash em uma estrada de cascalho que tem altas montanhas de um lado e uma queda de 200 pés no rio Bumburet do outro. As cores intensas e a vivacidade do local devem ser vividas para serem compreendidas.

O objetivo desta viagem de pesquisa, conduzida pelo Laboratório de Música e Ciências da Universidade de Durham, é descobrir como a percepção emocional da música pode ser influenciada pela origem cultural dos ouvintes e examinar se existem aspectos universais nas emoções transmitidas pela música . Para nos ajudar a entender essa questão, queríamos encontrar pessoas que não tivessem sido expostas à cultura ocidental.

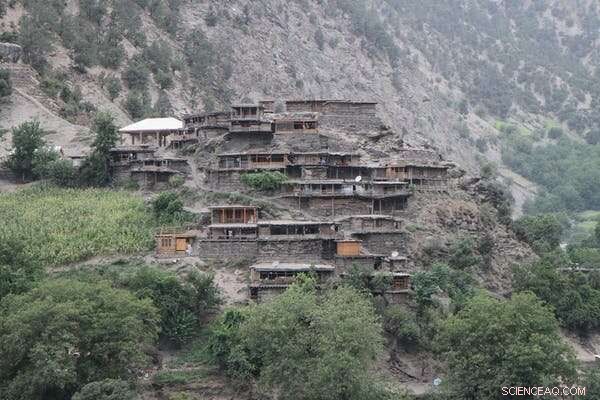

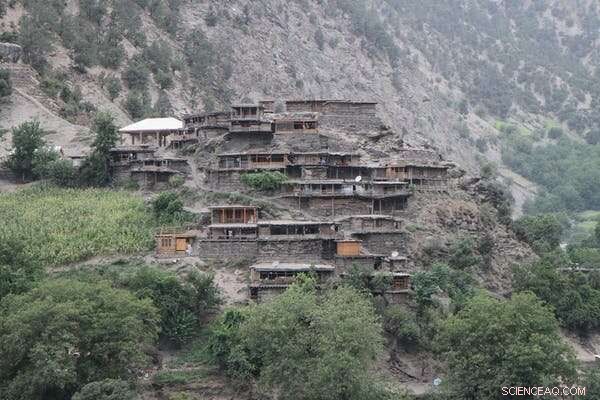

As aldeias que serão nossa base de operações estão espalhadas por três vales na fronteira entre o noroeste do Paquistão e o Afeganistão. Eles são o lar de várias tribos, embora nacional e internacionalmente sejam conhecidos como os vales Kalash (em homenagem à tribo Kalash). Apesar de sua população relativamente pequena, seus costumes únicos, religião politeísta, rituais e música os diferenciam de seus vizinhos.

A estrada de Chitral ao vale central de Kalash. Crédito:George Athanasopoulos, Autor fornecido

No campo Realizei pesquisas em locais como Papua Nova Guiné, Japão e Grécia. A verdade é que o trabalho de campo costuma ser caro, potencialmente perigoso e às vezes até fatal.

Mas, por mais difícil que seja realizar experimentos diante de barreiras linguísticas e culturais, a falta de um fornecimento estável de eletricidade para carregar nossas baterias estaria entre os obstáculos mais difíceis de superar nesta viagem. Os dados só podem ser coletados com a assistência e a vontade da população local. As pessoas que conhecemos literalmente se esforçaram mais por nós (na verdade, mais 16 milhas) para que pudéssemos recarregar nosso equipamento na cidade mais próxima com energia. Há pouca infra-estrutura nesta região do Paquistão. A usina hidrelétrica local fornece 200W para cada residência à noite, mas é propensa a mau funcionamento devido aos destroços após cada chuva, fazendo com que ela pare de operar a cada dois dias.

Uma vez superados os problemas técnicos, estávamos prontos para começar nossa investigação musical. Quando ouvimos música, confiamos muito em nossa memória da música que ouvimos ao longo de nossas vidas. Pessoas ao redor do mundo usam diferentes tipos de música para diferentes propósitos. E as culturas têm suas próprias formas estabelecidas de expressar temas e emoções através da música, assim como desenvolveram preferências por certas harmonias musicais. As tradições culturais moldam quais harmonias musicais transmitem felicidade e – até certo ponto – quanta dissonância harmônica é apreciada. Pense, por exemplo, no clima feliz de Here Comes the Sun, dos Beatles, e compare-o com a aspereza sinistra da trilha sonora de Bernard Herrmann para a infame cena do chuveiro em Psycho, de Hitchcock.

Assim, como nossa pesquisa teve como objetivo descobrir como a percepção emocional da música pode ser influenciada pela formação cultural dos ouvintes, nosso primeiro objetivo foi localizar participantes que não fossem predominantemente expostos à música ocidental. Isso é mais fácil dizer do que fazer, devido ao efeito abrangente da globalização e à influência que os estilos musicais ocidentais têm na cultura mundial. Um bom ponto de partida foi procurar lugares sem fornecimento estável de eletricidade e com poucas estações de rádio. Isso geralmente significaria uma conexão de internet ruim ou inexistente com acesso limitado a plataformas de música online – ou, de fato, qualquer outro meio de acesso à música global.

Um benefício da nossa localização escolhida foi que a cultura circundante não era orientada para o oeste, mas sim em uma esfera cultural completamente diferente. A cultura punjabi é a principal no Paquistão, pois os punjabi são o maior grupo étnico. Mas a cultura Khowari domina nos vales de Kalash. Menos de 2% falam urdu, a língua franca do Paquistão, como língua materna. O povo Kho (uma tribo vizinha ao Kalash), soma cerca de 300.000 e fazia parte do Reino de Chitral, um estado principesco que foi primeiro parte do Raj britânico e depois da República Islâmica do Paquistão até 1969. O mundo ocidental é visto pelas comunidades de lá como algo "diferente", "estrangeiro" e "não nosso".

O segundo objetivo foi localizar pessoas cuja própria música consiste em uma tradição de performance nativa estabelecida, na qual a expressão da emoção através da música é feita de maneira comparável ao ocidente. Isso porque, embora estivéssemos tentando escapar da influência da música ocidental nas práticas musicais locais, era importante que nossos participantes entendessem que a música poderia transmitir emoções diferentes.

Habitações de madeira no vale de Rumbur, um dos três vales habitados pelo povo Kalash no distrito de Chitral, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Paquistão. Crédito:Shutterstock/knovakov

Finalmente, precisávamos de um local onde nossas perguntas pudessem ser colocadas de uma maneira que permitisse aos participantes de diferentes culturas avaliar a expressão emocional na música ocidental e não ocidental.

Para o Kalash, a música não é um passatempo; é um identificador cultural. É um aspecto inseparável da prática ritual e não ritual, do nascimento e da vida. Quando alguém morre, eles são enviados ao som de música e dança, enquanto sua história de vida e seus feitos são recontados.

Enquanto isso, o povo Kho vê a música como uma das artes "educadas" e refinadas. Eles o usam para destacar os melhores aspectos de sua poesia. Their evening gatherings, typically held after dark in the homes of prominent members of the community, are comparable to salon gatherings in Enlightenment Europe, in which music, poetry and even the nature of the act and experience of thought are discussed. I was often left to marvel at how regularly men, who seemingly could bend steel with their piercing gaze, were moved to tears by a simple melody, a verse, or the silence which followed when a particular piece of music had just ended.

It was also important to find people who understood the concept of harmonic consonance and dissonance—that is, the relative attractiveness and unattractiveness of harmonies. This is something which can be easily done by observing whether local musical practices include multiple, simultaneous voices singing together one or more melodic lines. After running our experiments with British participants, we came to the Kalash and Kho communities to see how non-western populations perceive these same harmonies.

Our task was simple:expose our participants from these remote tribes to voice and music recordings which varied in emotional intensity and context, as well as some artificial music samples we had put together.

Major and minor A mode is the language or vocabulary that a piece of music is written in, while a chord is a set of pitches which sound together. The two most common modes in western music are major and minor. Here Comes the Sun by The Beatles is a song in a major scale, using only major chords, while Call Out My Name by the Weeknd is a song in a minor scale, which uses only minor chords. In western music, the major scale is usually associated with joy and happiness, while the minor scale is often associated with sadness.

Right away we found that people from the two tribes were reacting to major and minor modes in a completely different manner to our UK participants. Our voice recordings, in Urdu and German (a language very few here would be familiar with), were perfectly understood in terms of their emotional context and were rated accordingly. But it was less than clear cut when we started introducing the musical stimuli, as major and minor chords did not seem to get the same type of emotional reaction from the tribes in northwest Pakistan as they do in the west.

We began by playing them music from their own culture and asked them to rate it in terms of its emotional context; a task which they performed excellently. Then we exposed them to music which they had never heard before, ranging from West Coast Jazz and classical music to Moroccan Tuareg music and Eurovision pop songs.

While commonalities certainly exist—after all, no army marches to war singing softly, and no parent screams their children to sleep—the differences were astounding. How could it be that Rossini's humorous comic operas, which have been bringing laughter and joy to western audiences for almost 200 years, were seen by our Kho and Kalash participants to convey less happiness than 1980s speed metal?

We were always aware that the information our participants provided us with had to be placed in context. We needed to get an insider perspective on their train of thought regarding the perceived emotions.

Essentially, we were trying to understand the reasons behind their choices and ratings. After countless repetitions of our experiments and procedures and making sure that our participants had understood the tasks that we were asking them to do, the possibility started to emerge that they simply did not prefer the consonance of the most common western harmonies.

Not only that, but they would go so far as to dismiss it as sounding "foreign." Indeed, a recurring trope when responding to the major chord was that it was "strange" and "unnatural," like "European music." That it was "not our music."

Melody harmonised in the style of a J.S. Bach chorale. What is natural and what is cultural? Once back from the field, our research team met up and together with my colleagues Dr. Imre Lahdelma and Professor Tuomas Eerola we started interpreting the data and double checking the preliminary results by putting them through extensive quality checks and number crunching with rigorous statistical tests. Our report on the perception of single chords shows how the Khalash and Kho tribes perceived the major chord as unpleasant and negative, and the minor chord as pleasant and positive.

To our astonishment, the only thing the western and the non-western responses had in common was the universal aversion to highly dissonant chords. The finding of a lack of preference for consonant harmonies is in line with previous cross-cultural research investigating how consonance and dissonance are perceived among the Tsimané, an indigenous population living in the Amazon rainforest of Bolivia with limited exposure to western culture. Notably, however, the experiment conducted on the Tsimané did not include highly dissonant harmonies in the stimuli. So the study's conclusion of an indifference to both consonance and dissonance might have been premature in the light of our own findings.

When it comes to emotional perception in music, it is apparent that a large amount of human emotions can be communicated across cultures at least on a basic level of recognition. Listeners who are familiar with a specific musical culture have a clear advantage over those unfamiliar with it—especially when it comes to understanding the emotional connotations of the music.

But our results demonstrated that the harmonic background of a melody also plays a very important role in how it is emotionally perceived. See, for example, Victor Borge's Beethoven variation on the melody of Happy Birthday, which on its own is associated with joy, but when the harmonic background and mode changes the piece is given an entirely different mood.

Then there is something we call "acoustic roughness," which also seems to play an important role in harmony perception—even across cultures. Roughness denotes the sound quality that arises when musical pitches are so close together that the ear cannot fully resolve them. This unpleasant sound sensation is what Bernard Herrmann so masterfully uses in the aforementioned shower scene in Psycho. This acoustic roughness phenomenon has a biologically determined cause in how the inner ear functions and its perception is likely to be common to all humans.

According to our findings, harmonisations of melodies that are high in roughness are perceived to convey more energy and dominance—even when listeners have never heard similar music before. This attribute has an affect on how music is emotionally perceived, particularly when listeners lack any western associations between specific music genres and their connotations.

The same melody harmonised in a wholetone style. For example, the Bach chorale harmonization in major mode of the simple melody below was perceived as conveying happiness only to our British participants. Our Kalash and Kho participants did not perceive this particular style to convey happiness to a greater degree than other harmonisations.

The wholetone harmonization below, on the other hand, was perceived by all listeners—western and non-western alike—to be highly energetic and dominant in relation to the other styles. Energy, in this context, refers to how music may be perceived to be active and "awake," while dominance relates to how powerful and imposing a piece of music is perceived to be.

Carl Orff's O Fortuna is a good example of a highly energetic and dominant piece of music for a western listener, while a soft lullaby by Johannes Brahms would not be ranked high in terms of dominance or energy. At the same time, we noted that anger correlated particularly well with high levels of roughness across all groups and for all types of real (for example, the Heavy Metal stimuli we used) or artificial music (such as the wholetone harmonization below) that the participants were exposed to.

So, our results show both with single, isolated chords and with longer harmonisations that the preference for consonance and the major-happy, minor-sad distinction seems to be culturally dependent. These results are striking in the light of tradition handed down from generation to generation in music theory and research. Western music theory has assumed that because we perceive certain harmonies as pleasant or cheerful this mode of perception must be governed by some universal law of nature, and this line of thinking persists even in contemporary scholarship.

Indeed, the prominent 18th century music theorist and composer Jean-Philippe Rameau advocated that the major chord is the "perfect" chord, while the later music theorist and critic Heinrich Schenker concluded that the major is "natural" as opposed to the "artificial" minor.

But years of research evidence now shows that it is safe to assume that the previous conclusions of the "naturalness" of harmony perception were uninformed assumptions, and failed even to attempt to take into account how non-western populations perceive western music and harmony.

Just as in language we have letters that build up words and sentences, so in music we have modes. The mode is the vocabulary of a particular melody. One erroneous assumption is that music consists of only the major and minor mode, as these are largely prevalent in western mainstream pop music.

In the music of the region where we conducted our research, there are a number of different, additional modes which provide a wide range of shades and grades of emotion, whose connotation may change not only by core musical parameters such as tempo or loudness, but also by a variety of extra-musical parameters (performance setting, identity, age and gender of the musicians).

For example, a video of the late Dr. Lloyd Miller playing a piano tuned in the Persian Segah dastgah mode shows how so many other modes are available to express emotion. The major and minor mode conventions that we consider as established in western tonal music are but one possibility in a specific cultural framework. They are not a universal norm.

Why is this important? Research has the potential to uncover how we live and interact with music, and what it does to us and for us. It is one of the elements that makes the human experience more whole. Whatever exceptions exist, they are enforced and not spontaneous, and music, in some form, is present in all human cultures. The more we investigate music around the world and how it affects people, the more we learn about ourselves as a species and what makes us

feel .

Our findings provide insights, not only into intriguing cultural variations regarding how music is perceived across cultures, but also how we respond to music from cultures which are not our own. Can we not appreciate the beauty of a melody from a different culture, even if we are ignorant to the meaning of its lyrics? There are more things that connect us through music than set us apart.

When it comes to musical practices, cultural norms can appear strange when viewed from an outsider's perspective. For example, we observed a Kalash funeral where there was lots of fast-paced music and highly-energetic dancing. A western listener might wonder how it is possible to dance with such vivacity to music which is fast, rough and atonal—at a funeral.

But at the same time, a Kalash observer might marvel at the sombreness and quietness of a western funeral:was the deceased a person of so little importance that no sacrifices, honorary poems, praise songs and loud music and dancing were performed in their memory? As we assess the data captured in the field a world away from our own, we become more aware of the way music shapes the stories of the people who make it, and how it is shaped by culture itself.

After we had said our goodbyes to our Kalash and Kho hosts, we boarded a truck, drove over the dangerous Lowari Pass from Chitral to Dir, and then traveled to Islamabad and on to Europe. And throughout the trip, I had the words of a Khowari song in my mind:"The old path, I burn it, it is warm like my hands. In the young world, you will find me."