Como podemos distinguir melhor a desinformação de um consenso confiável de especialistas?

O presidente dos EUA, Donald Trump, fez falsas alegações de fraude eleitoral generalizada durante as eleições presidenciais de 2020. Pesquisadores da UNSW Psychology descobriram agora uma maneira de as pessoas não serem enganadas com as chamadas “notícias falsas” de uma única fonte. Crédito:Shutterstock

Se mais pessoas lhe dissessem que algo era verdade, você pensaria que tenderia a acreditar.

Não de acordo com um estudo de 2019 da Universidade de Yale, que descobriu que as pessoas acreditam em uma única fonte de informação que é repetida em muitos canais (um 'falso consenso'), tão prontamente quanto várias pessoas dizendo algo baseado em muitas fontes originais independentes (um 'verdadeiro consenso').

A descoberta mostrou como a desinformação pode ser reforçada e teve ramificações para decisões importantes que tomamos com base em conselhos que recebemos de lugares como governos e mídia sobre informações como vacinas, uso de máscaras durante a pandemia ou até em quem votamos em uma eleição .

A descoberta da 'ilusão de consenso' de 2019 fascinou o pesquisador de pós-doutorado da Escola de Psicologia da UNSW Science, Saoirse Connor Desai, que testou a descoberta da ilusão e encontrou uma maneira de as pessoas não serem enganadas com as chamadas 'notícias falsas' de um Fonte única.

O estudo de sua equipe foi publicado em

Cognition .

"Descobrimos que a ilusão pode ser reduzida quando damos às pessoas informações sobre como as fontes originais usaram evidências para chegar a suas conclusões", diz o Dr. Connor Desai.

Ela diz que a descoberta é particularmente relevante para as melhores práticas de comunicação científica – por exemplo. como os formuladores de políticas ou a mídia apresentam às pessoas evidências científicas ou pesquisas especializadas.

Por exemplo, mais de 80% dos blogs de negação da mudança climática repetem afirmações de uma única pessoa que afirma ser um 'especialista em ursos polares'.

"Você pode ter uma situação em que uma proposta de saúde enganosa é repetida por vários canais, o que pode influenciar as pessoas a confiar nessa informação mais do que deveriam, porque acham que há evidências disso ou acham que há um consenso", disse. Dr. Connor Desai diz.

"Mas nossa descoberta mostra que, se você puder explicar às pessoas de onde vem sua informação e como as fontes originais chegaram às suas conclusões, isso fortalece sua capacidade de identificar um 'consenso verdadeiro'."

Dr. Connor Desai diz que a descoberta do estudo de Yale foi surpreendente para ela, "porque parecia ser uma acusação da capacidade humana de distinguir entre o verdadeiro consenso e o falso consenso".

"O estudo original mostrou que as pessoas são rotineiramente ruins nisso. Houve muitas situações em que elas nunca são capazes de dizer a diferença entre o verdadeiro e o falso consenso", diz ela.

“É problemático porque se as pessoas ouvirem as declarações falsas ou enganosas de uma única pessoa repetidas por diferentes canais, elas podem sentir que a declaração é mais válida do que é”.

Dr. Connor Desai says an example of this is multiple independent experts agreeing that Ivermectin should not be used to treat COVID-19 (true consensus), versus a single group or individual saying that people should use it as an anti-viral drug (false consensus).

How the study was conducted The aim of the UNSW study was to understand why people believe false information when it's repeated.

"Our main goal was to establish whether one reason that people are equally convinced by true and false consensus is that they assume that different sources share data or methodologies," Dr. Connor Desai says.

"Do they understand there is potentially more evidence when you have multiple experts saying the same thing?"

The UNSW researchers conducted several experiments.

The first experiment replicated the 2019 Yale study, which saw participants given a variety of articles about a fictional tax policy which took positive, negative, or neutral stances, and then asked to what extent they agreed the proposal would improve the economy.

It replicated the "illusion of consensus" where people are equally convinced by one piece of evidence as they are by many pieces of evidence but added a new condition where they told people who saw a "true consensus" that the sources had used different data and methods to arrive at their conclusions.

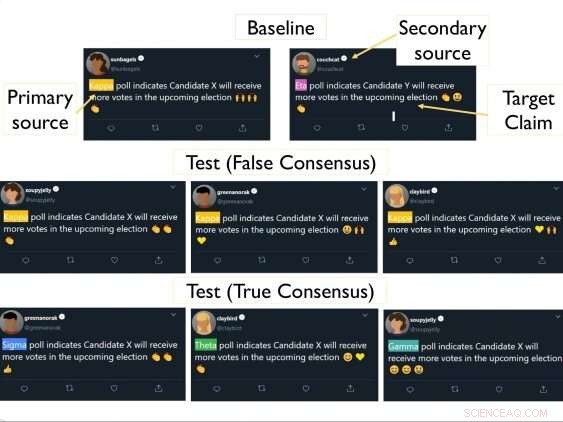

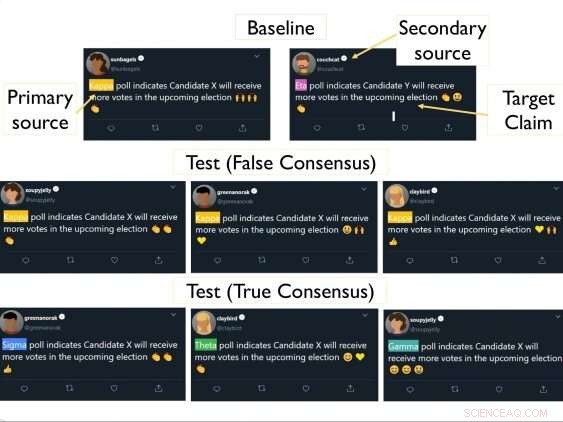

An example of the made up Twitter posts used in the study.

The result was a reduction in the illusion of consensus.

"People were more convinced by true consensus than false consensus."

In another experiment, 200 participants were given information about an election in a fictional foreign democratic country.

They were shown fictional Twitter posts from news outlets that said which candidates would get more votes in the election:some sourced the same or different pollsters to predict a candidate would win, while another tweet said a different contender would win.

But in the true consensus Twitter posts, they gave people a scenario in which it was clear that different primary sources worked independently and used different data to arrive at their conclusions.

"We expected that many people would be more familiar with such polls and would realize that looking at multiple different polls would be a better way of predicting the election result than just seeing a single poll multiple times," Dr. Connor Desai says.

After reading the tweets, participants rated which candidate would win based on the polling predictions.

"It seemed that people were more convinced by a true consensus than a false consensus when they understood the pollsters had gathered evidence independently of one another," Professor of Cognitive Psychology in the School of Psychology, Brett Hayes says.

"Our results suggest that people do see claims endorsed by multiple sources as stronger when they believe these sources really are independent of one another."

The researchers later replicated and extended the tweet study with 365 more participants.

"This time we had a condition where the tweets came from individual people who showed their endorsement of the polls using emojis," Dr. Connor Desai says.

"Regardless of whether the tweets came from news outlets, or individual tweeters, people were more convinced by true than false consensus when the relationship between sources was unambiguous."

False consensus not completely discounted But the researchers also found the participants didn't completely discount false consensus.

"There are at least two possible explanations for this effect," Dr. Connor Desai said.

"The first is that such repetition simply increases the familiarity of the claim—enhancing its memory representation, and this is sufficient to increase confidence.

"The second is that people may make inferences about why a claim is repeated because the source believed it was the most reputable or provided the strongest evidence.

"For instance, if different news channels all cite the same expert you might think that they're citing the same person because they are the most qualified to talk about whatever it is they're talking about."

Dr. Connor Desai plans to next look at why some communication strategies are more effective than others, and if repeating information is always effective.

"Is there a point where there's too much consensus, and people become suspicious?" she says.

"Can you correct a 'false consensus' by pointing out that it's often better to get information from multiple independent sources? These are the kinds of strategies we wish to look into."