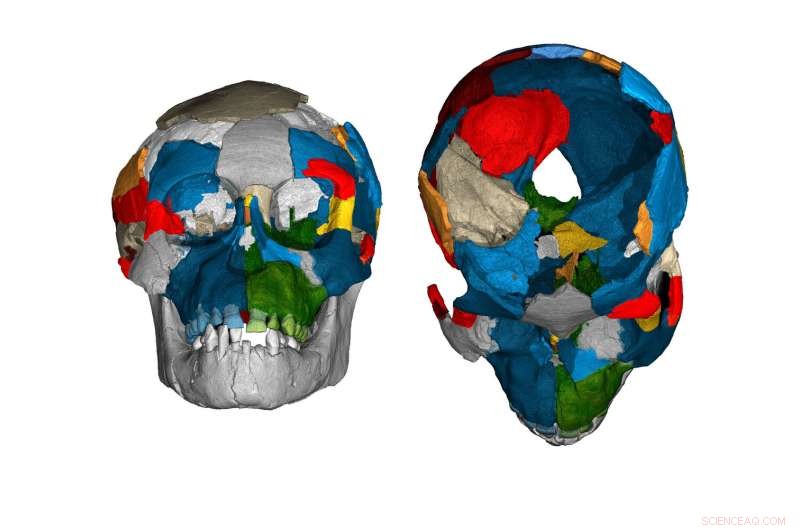

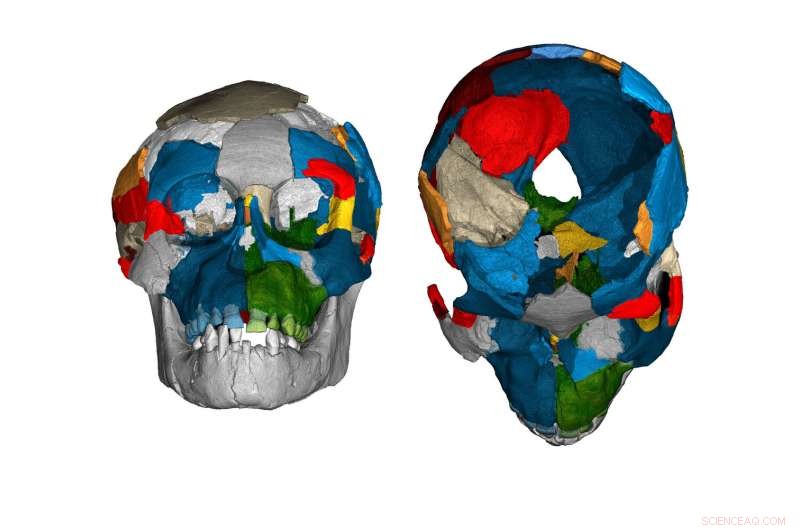

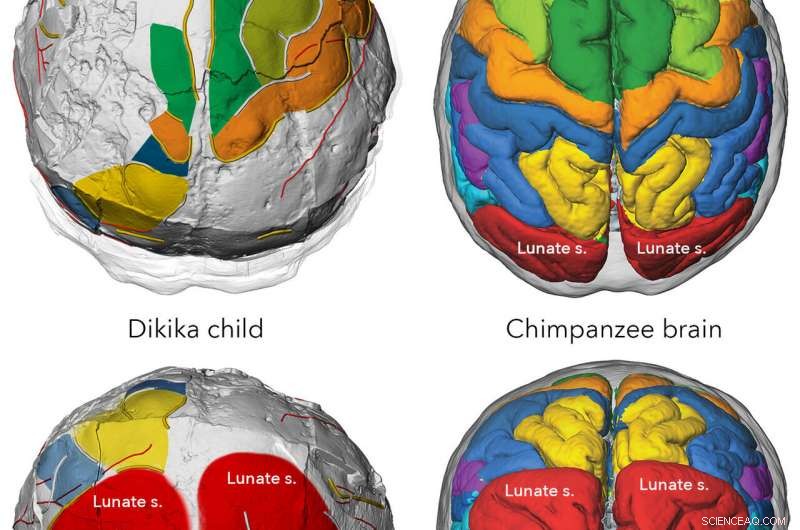

p Impressões cerebrais em crânios fósseis da espécie Australopithecus afarensis (famoso por "Lucy" e a "criança Dikika" da Etiópia retratada aqui) lançou uma nova luz sobre a evolução do crescimento e da organização do cérebro. A marca endocraniana excepcionalmente preservada da criança Dikika revela uma organização cerebral semelhante a um macaco, e nenhuma característica derivada para humanos. Crédito:Philipp Gunz, MPI EVA Leipzig.

p Impressões cerebrais em crânios fósseis da espécie Australopithecus afarensis (famoso por "Lucy" e a "criança Dikika" da Etiópia retratada aqui) lançou uma nova luz sobre a evolução do crescimento e da organização do cérebro. A marca endocraniana excepcionalmente preservada da criança Dikika revela uma organização cerebral semelhante a um macaco, e nenhuma característica derivada para humanos. Crédito:Philipp Gunz, MPI EVA Leipzig.

p Os cientistas há muito tempo medem e analisam os crânios fósseis de nossos ancestrais para estimar o volume e o crescimento do cérebro. A questão de como esses cérebros antigos se comparam aos cérebros humanos modernos e aos cérebros de nosso primo primata mais próximo, o chimpanzé, continua a ser um dos principais alvos de investigação. p Um novo estudo publicado em

Avanços da Ciência usou a tecnologia de tomografia computadorizada para visualizar impressões cerebrais de três milhões de anos dentro de crânios fósseis da espécie

Australopithecus afarensis (famoso por "Lucy" e "Selam" da região de Afar da Etiópia) para lançar uma nova luz sobre a evolução da organização e do crescimento do cérebro. A pesquisa revela que, embora a espécie de Lucy tivesse uma estrutura cerebral semelhante à de um macaco, o cérebro demorou mais para atingir o tamanho adulto, sugerindo que os bebês podem ter tido uma dependência mais longa dos cuidadores, um traço semelhante ao humano.

p A tomografia computadorizada permitiu aos pesquisadores chegar a duas questões de longa data que não poderiam ser respondidas por observação visual e medição apenas:Há evidências de reorganização do cérebro humano em

Australopithecus afarensis , e o padrão de crescimento do cérebro nessa espécie era mais semelhante ao dos chimpanzés ou dos humanos?

p Para estudar o crescimento e a organização do cérebro em

A. afarensis , Os pesquisadores, incluindo o paleoantropólogo da ASU William Kimbel, digitalizou oito fósseis de crânios dos sítios etíopes de Dikika e Hadar usando tomografia computadorizada convencional e síncrotron de alta resolução. Kimbel, líder do trabalho de campo em Hadar, é diretora do Instituto de Origens Humanas e Professora Virginia M. Ullman de História Natural e Meio Ambiente na Escola de Evolução Humana e Mudança Social.

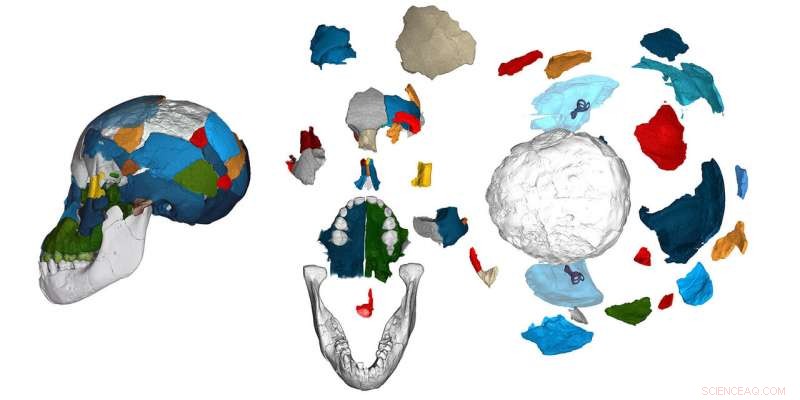

Impressões cerebrais de 3 milhões de anos em crânios fósseis da espécie Australopithecus afarensis (famosa por “Lucy” e a “criança Dikika” da Etiópia mostrada aqui) lançam uma nova luz sobre a evolução do crescimento e organização do cérebro. Crédito:Paul Tafforeau, ESRF Grenoble p A espécie de Lucy habitou a África oriental há mais de três milhões de anos - a própria "Lucy" tem 3,2 milhões de anos - e ocupa uma posição-chave na árvore genealógica dos hominídeos, como é amplamente aceito como ancestral de todos os hominídeos posteriores, incluindo a linhagem que conduz aos humanos modernos.

p "Lucy e seus parentes fornecem evidências importantes sobre o comportamento dos primeiros hominídeos - eles andavam eretos, tinham cérebros que eram cerca de 20 por cento maiores do que os dos chimpanzés, e pode ter usado ferramentas de pedra afiadas, "explica o co-autor Zeresenay Alemseged (Universidade de Chicago), que dirige o projeto de campo Dikika na Etiópia e é um Afiliado de Pesquisa Internacional do Instituto de Origens Humanas.

p Cérebros não fossilizam, mas à medida que o cérebro cresce e se expande antes e depois do nascimento, os tecidos ao redor de sua camada externa deixam uma marca no interior da caixa craniana óssea. Os cérebros dos humanos modernos não são apenas muito maiores do que os de nossos parentes macacos vivos mais próximos, mas também são organizados de maneira diferente e levam mais tempo para crescer e amadurecer. Comparado com os chimpanzés, bebês humanos modernos aprendem mais e são inteiramente dependentes dos cuidados dos pais por longos períodos de tempo. Juntos, essas características são importantes para a cognição humana e o comportamento social, mas suas origens evolutivas permanecem obscuras.

p Cérebros não fossilizam, mas conforme o cérebro cresce, os tecidos ao redor de sua camada externa deixam uma marca na caixa craniana óssea. A impressão endocraniana da criança Dikika revela uma organização cerebral semelhante a um macaco, e nenhuma característica derivada para humanos. Crédito:Philipp Gunz, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

p Cérebros não fossilizam, mas conforme o cérebro cresce, os tecidos ao redor de sua camada externa deixam uma marca na caixa craniana óssea. A impressão endocraniana da criança Dikika revela uma organização cerebral semelhante a um macaco, e nenhuma característica derivada para humanos. Crédito:Philipp Gunz, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

p As tomografias computadorizadas resultaram em "endocasts" digitais de alta resolução do interior dos crânios, onde a estrutura anatômica do cérebro pode ser visualizada e analisada. Com base nessas endocasts, the researchers could measure brain volume and infer key aspects of cerebral organization from impressions of the brain's structure.

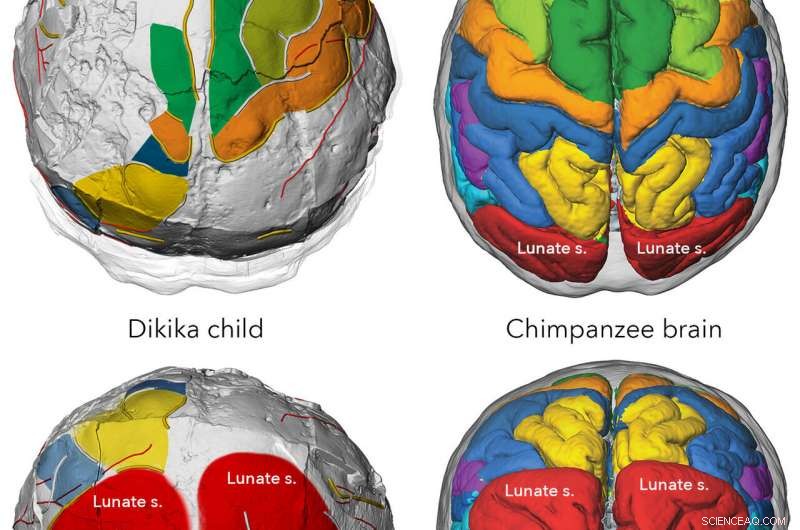

p A key difference between apes and humans involves the organization of the brain's parietal lobe—important in the integration and processing of sensory information—and occipital lobe in the visual center at the rear of the brain. The exceptionally preserved endocast of "Selam, " a skull and associated skeleton of an

Australopithecus afarensis infant found at Dikika in 2000, has an unambiguous impression of the lunate sulcus—a fissure in the occipital lobe marking the boundary of the visual area that is more prominent and located more forward in apes than in humans—in an ape-like position. The scan of the endocranial imprint of an adult

A. afarensis fossil from Hadar (A.L. 162-28) reveals a previously undetected impression of the lunate sulcus, which is also in an ape-like position.

p Some scientists had conjectured that human-like brain reorganization in australopiths was linked to behaviors that were more complex than those of their great ape relatives (e.g., stone-tool manufacture, mentalizing, and vocal communication). Infelizmente, the lunate sulcus typically does not reproduce well on endocasts, so there was unresolved controversy about its position in

Australopithecus .

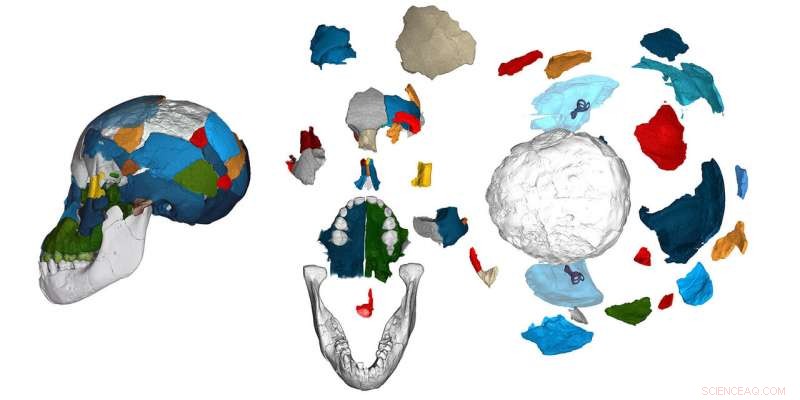

p Brain imprints (shown in white) in fossil skulls of the species Australopithecus afarensis shed new light on the evolution of brain growth and organization. Several years of painstaking fossil reconstruction, and counting of dental growth lines, yielded an exceptionally preserved brain imprint of the Dikika child, and a precise age at death. Credit:Philipp Gunz, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

p Brain imprints (shown in white) in fossil skulls of the species Australopithecus afarensis shed new light on the evolution of brain growth and organization. Several years of painstaking fossil reconstruction, and counting of dental growth lines, yielded an exceptionally preserved brain imprint of the Dikika child, and a precise age at death. Credit:Philipp Gunz, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

p "A highlight of our work is how cutting-edge technology can clear up long-standing debates about these three million-year-old fossils, " notes coauthor Kimbel. "Our ability to 'peer' into the hidden details of bone and tooth structure with CT scans has truly revolutionized the science of our origins."

p A comparison of infant and adult endocranial volumes also indicates more human-like protracted brain growth in

Australopithecus afarensis , likely critical for the evolution of a long period of childhood learning in hominins.

p In infants, CT scans of the dentition make it possible to determine an individual's age at death by counting dental growth lines. Similar to the growth rings of a tree, virtual sections of a tooth reveal incremental growth lines reflecting the body's internal rhythm. Studying the fossilized teeth of the Dikika infant, the team's dental experts calculated an age at death of 2.4 years.

Brain imprints in fossil skulls of the species Australopithecus afarensis (famous for “Lucy”, and the “Dikika child” from Ethiopia shown here) shed new light on the evolution of brain growth and organization. Several years of painstaking fossil reconstruction, and counting of dental growth lines, yielded an exceptionally preserved brain imprint of the Dikika child, and a precise age at death. These data suggest that Australopithecus afarensis had an ape-like brain and prolonged brain growth. Credit:Philipp Gunz, MPI EVA Leipzig p The pace of dental development of the Dikika infant was broadly comparable to that of chimpanzees and therefore faster than in modern humans. But given that the brains of

Australopithecus afarensis adults were roughly 20 percent larger than those of chimpanzees, the Dikika child's small endocranial volume suggests a prolonged period of brain development relative to chimpanzees.

p "The combination of apelike brain structure and humanlike protracted brain growth in Lucy's species was unexpected, " says Kimbel. "That finding supports the idea that human brain evolution was very much a piecemeal affair, with extended brain growth appearing before the origin of our own genus,

Homo . "

Brain imprints in fossil skulls of the species Australopithecus afarensis (famous for “Lucy”, and the “Dikika child” from Ethiopia pictured here) shed new light on the evolution of brain growth and organization. Several years of painstaking fossil reconstruction, and counting of dental growth lines, yielded an exceptionally preserved brain imprint of the Dikika child, and a precise age at death. These data suggest that Australopithecus afarensis had an ape-like brain and prolonged brain growth. Credit:Philipp Gunz, MPI EVA Leipzig p Among primates, different rates of growth and maturation are associated with different infant-care strategies, suggesting that the extended period of brain growth in

Australopithecus afarensis may have been linked to a long dependence on caregivers. Alternativamente, slow brain growth could also primarily represent a way to spread the energetic requirements of dependent offspring over many years in environments where food is not always abundant. Em ambos os casos, protracted brain growth in

Australopithecus afarensis provided the basis for subsequent evolution of the brain and social behavior in hominins and was likely critical for the evolution of a long period of childhood learning.