Lutas de peixes:a Grã-Bretanha tem uma longa história de comércio de acesso às águas costeiras

p Uma traineira de Brixham do século 19 por William Adolphus Knell. Crédito:Museu Marítimo Nacional / Wikipedia

p Uma traineira de Brixham do século 19 por William Adolphus Knell. Crédito:Museu Marítimo Nacional / Wikipedia

p Os barcos britânicos foram superados em número por cerca de oito para um pelos franceses. Em pouco tempo, houve colisões e projéteis foram lançados. Os britânicos foram forçados a recuar, voltando ao porto com as janelas quebradas, mas felizmente sem feridos. p O conflito por trás dessa escaramuça entre pescadores britânicos e franceses na Baía de Seine no final de agosto de 2018 foi rapidamente apelidado de "guerra das vieiras" na imprensa. Os franceses vinham tentando impedir as dragas de vieiras britânicas de pescar legalmente os leitos em águas nacionais francesas. Mas o incidente expôs tensões que vêm crescendo há muitos anos.

p No âmbito da Política Comum das Pescas (PCP) da União Europeia, os pescadores britânicos tinham o direito legal de pescar nessas águas, assim como qualquer barco de um estado membro da UE. A complicação veio de uma regulamentação francesa que impedia os barcos locais de pescar nessas águas entre 16 de maio e 30 de setembro de cada ano, para permitir a recuperação dos estoques da safra anual. Mas sob o CFP, um país da UE não tem autoridade para impedir a frota de outro Estado-Membro de pescar nas suas águas.

p Esta peculiaridade do CFP deixou os pescadores franceses incapazes de dragar vieiras até 1 de outubro, e forçados a ficar parados e assistir enquanto frotas de outros países coletavam o que consideravam um recurso francês em águas francesas. Quando os barcos britânicos chegaram, os pescadores franceses assumiram o papel de guardiões de seus recursos, ações que eles acreditavam serem justificadas, mas vistas pela indústria pesqueira britânica como ilegais.

p Este incidente em um pequeno canto de um mar compartilhado da UE foi resolvido em poucas semanas, graças a um novo acordo sobre como os dois países compartilhariam a colheita de vieiras. Mas as tensões subjacentes que o CFP criou sobre a partilha dos recursos nacionais são muito mais profundas, com a sensação de que as regras não permitem o uso justo dos mares.

p Esse sentimento de injustiça foi obviamente expresso no papel que a pesca desempenhou na decisão da Grã-Bretanha de deixar a UE. Os ativistas prometeram que "retomar o controle" das águas britânicas permitiria ao país reviver sua indústria pesqueira há muito decadente e as comunidades que dependem dela.

p No entanto, independentemente do impacto que a PCP teve sobre os pescadores britânicos, seu futuro após o Brexit depende muito de qualquer futuro acordo comercial que o governo negocie com a UE. E a história de como a Grã-Bretanha respondeu aos conflitos sobre direitos de pesca muito maiores do que a guerra das vieiras não augura nada de bom para o setor.

p

O início do declínio

p Pesquisas sobre a atividade pesqueira mostram que o declínio da indústria pesqueira britânica começou muito antes da criação de qualquer política pesqueira europeia. Na verdade, suas origens finais podem ser rastreadas até uma fonte surpreendente:a expansão das ferrovias no final do século XIX.

p Arrasto, sob o poder da vela, já existia há mais de 500 anos. Mas sem refrigeração, o peixe só poderia ser entregue para venda em áreas próximas aos portos. A chegada da rede ferroviária significou que os peixes puderam ser transportados para o interior para grandes cidades e vilas.

p Para atender ainda mais a essa demanda crescente, os arrastões a vapor começaram a substituir os arrastões à vela a partir de 1880. A potência desses navios a vapor aumentou muito o escopo da pesca de arrasto e permitiu que eles navegassem por mais tempo e mais longe do porto, enquanto rebocavam redes maiores. Os arrastões a vapor britânicos aventuraram-se mais longe da Grã-Bretanha em busca de peixes, com os pesqueiros se expandindo para áreas tão distantes quanto a Groenlândia, norte da Noruega e Mar de Barent, Islândia e Ilhas Faroé.

p Mas já em 1885, foram levantadas preocupações de que esse avanço na tecnologia estava tendo um impacto negativo sobre os estoques pesqueiros e seu habitat. As evidências dos registros da atividade pesqueira mostram que essa melhoria na tecnologia e o aumento do tamanho da frota pesqueira foram diretamente responsáveis pelo aumento dos desembarques.

p O boom da pesca que as ferrovias desencadearam se mostrou insustentável, e a sobrepesca resultante acabaria por enviar a indústria a uma desaceleração de longo prazo. Depois de décadas de mais e mais pesca, os desembarques começaram a diminuir após a Segunda Guerra Mundial, uma tendência que continuou ao longo da segunda metade do século 20 e no novo milênio.

p Para compensar, o tamanho e a força da frota continuaram a aumentar à medida que mais esforço era necessário para capturar peixes cada vez mais escassos. Desde o final dos anos 1950, a quantidade de peixes desembarcados por unidade de potência diminuiu a uma taxa mais rápida do que os desembarques de peixes, como a frota continuou a despender mais e mais esforços para manter o tamanho das capturas. Contudo, esse esforço foi em vão e, em 1980, as capturas haviam caído ao ponto mais baixo em um século.

p Odinn da Islândia e HMS Scylla se enfrentam no Atlântico Norte durante a ‘Terceira Guerra do Bacalhau’ na década de 1970. Crédito:Isaac Newton / www.hmsbacchante.co.uk

p Odinn da Islândia e HMS Scylla se enfrentam no Atlântico Norte durante a ‘Terceira Guerra do Bacalhau’ na década de 1970. Crédito:Isaac Newton / www.hmsbacchante.co.uk

p

Guerra do bacalhau

p A sobrepesca não foi a única razão para o declínio, Contudo. A queda dos estoques de peixes, combinada com as melhorias no alcance e na potência da frota nos anos do pós-guerra, levou os pescadores britânicos a buscarem novas águas, com mais barcos se afastando do Reino Unido para capturar peixes suficientes para atender à demanda doméstica. E essa pesca de arrasto de longo alcance colocou a frota do Reino Unido em conflito com a Islândia.

p Os pescadores britânicos pescavam nessas águas desde o século 15. Contudo, A indústria pesqueira da Islândia começou a se ressentir disso quando os arrastões a vapor começaram a pescar ao largo da Islândia no final do século XIX. Isso levou a acusações de que os arrastões britânicos estavam danificando as áreas de pesca e esgotando os estoques. Em 1952, A Islândia declarou uma zona de seis quilômetros ao redor de seu país para impedir a pesca estrangeira excessiva, embora os peixes não se fixem nas fronteiras criadas pelo homem e os estoques ainda possam ser esgotados fora desta zona. A decisão da Islândia atraiu uma resposta do Reino Unido, que proibiu a importação de peixes islandeses. Como um importante mercado de exportação para a indústria mais importante da Islândia, eles esperavam que isso os levasse à mesa de negociações.

p Em 1958, contra um pano de fundo de diplomacia fracassada, A Islândia expandiu esta zona para 12 milhas e proibiu as frotas estrangeiras de pescar nessas águas, em desafio ao direito internacional. Isso levou ao primeiro do que ficou conhecido como a Guerra do Bacalhau - um ato em três fases que durou quase 20 anos.

p Durante a primeira Guerra do Bacalhau, As fragatas da Marinha Real acompanharam a frota do Reino Unido na zona de exclusão da Islândia para continuar a pesca. Seguiu-se um jogo de gato e rato entre os navios da Guarda Costeira islandesa e os arrastões britânicos. Em resposta às tentativas de apreendê-los, os arrastões colidiram com os navios da guarda costeira e a guarda costeira ameaçou abrir fogo, embora grandes incidentes tenham sido evitados.

p Em 1961, os dois países finalmente chegaram a um acordo que permitiu à Islândia manter sua zona de 12 milhas. Em troca, o Reino Unido obteve acesso condicional a essas águas.

p Em 1972, Contudo, a sobrepesca fora deste limite piorou e a Islândia estendeu sua zona exclusiva para 50 milhas e, três anos depois, a 200 milhas. Ambos os movimentos levaram a mais confrontos entre os arrastões islandeses e os navios de escolta da Marinha Real, respectivamente apelidado de segundo e terceiro Cod Wars.

p Os navios da Guarda Costeira islandesa rebocaram dispositivos projetados para cortar os fios de aço da rede de arrasto (amarras) dos arrastões britânicos - e os navios de todos os lados estavam envolvidos em colisões deliberadas. Embora esses confrontos fossem principalmente sem sangue, a British fisher was seriously injured when he was hit by a severed hawser and an Icelandic engineer died while repairing damage to a trawler that had clashed with a Royal Navy frigate.

p In January 1976, British naval frigate HMS Andromeda collided with Thor, an Icelandic gunboat, which also sustained a hole in its hull. While British officials called the collision a "deliberate attack", the Icelandic Coastguard accused the Andomeda of ramming Thor by overtaking and then changing course. Eventually NATO intervened and another agreement was reached in May 1976 over UK access and catch limits. This agreement gave 30 vessels access to Iceland's waters for six months.

p NATO's involvement in the dispute had little to do with fisheries and a large amount to do with the Cold War. Iceland was a member of NATO, and therefore aligned to the US, with a substantial US military presence in Iceland at the time. Iceland believed that NATO should intervene in the dispute but it had up until that point resisted. Popular feeling against NATO grew in Iceland and the US became concerned that this strategically important island nation – which allowed control of the Greenland Iceland UK (GIUK) gap, an anti-submarine choke point – could leave NATO and worse, align itself with the Soviets.

p Amid protests at the US military base in Iceland demanding the expulsion of the Americans, and growing calls from Icelandic politicians that they should leave NATO, the US put pressure on the British to concede in order to protect the NATO alliance. The agreement brought to an end more than 500 years of unrestricted British fishing in these waters.

p The loss of these Atlantic fishing grounds cost 1, 500 jobs in the home ports of the UK's distant water fleet, concentrated around Scotland and the north-east of England, with many more jobs lost in shore-based support industries. This had a significant negative impact on the fishing communities in these areas.

p The UK also established its own 200-mile limit in response to Iceland's exclusion zone. These limits were eventually incorporated in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, giving similar rights to every sovereign nation. The creation of these "exclusive economic zones" (EEZ) was the first time that the international community had recognised that nations could own all of the resources that existed within the seas that surrounded them and exclude other nations from exploiting these resources.

p The UK now owned the rights to the 200-mile zone around its islands, which contained some of the richest fishing grounds in Europe but up until this point the principle of "open seas" had existed, with Britain its most vocal champion. Fishing nations, had fished the high seas within 200 miles of their own and others coasts for centuries and now were restricted to their own.

p British trawler Coventry City passes Icelandic Coastguard patrol vessel Albert off the Westfjords in 1958 during the first Cod War. Credit:Kjallakr/Wikipedia

p British trawler Coventry City passes Icelandic Coastguard patrol vessel Albert off the Westfjords in 1958 during the first Cod War. Credit:Kjallakr/Wikipedia

p

Economic trade offs

p Britain's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), Contudo, wasn't that exclusive.

p On joining the European Economic Community (the forerunner to the EU) in 1972, the UK had agreed to a policy of sharing access to its waters with all member states, and gaining access to the waters of other countries in return. The UN convention effectively gave the EEC one giant EEZ.

p The UK government was willing to enter into the agreement as fisheries were one part of overall negotiations that would allow the UK to export goods and services to the European continent with significantly reduced trade barriers.

p Although the fishing industry is of high local importance to fishing communities, it is relatively unimportant to the UK economy as a whole. Em 2016, the UK fishing industry (which includes the catching sector and all associated industries) was valued at £1.6 billion, against £1.76 trillion for the UK economy as a whole – or just under 1%. The UK's trade with the EU, both import and export, stands at £615 billion a year in comparison.

p

Enter the Common Fisheries Policy

p Em 1983, the Common Fisheries Policy was adopted, introducing management of European waters by giving each state a quota for what it could catch, based on a pre-determined percentage of total fishing opportunities. This was known as "relative stability" and was based on each country's historic fishing activity before 1983, which still determines how quotas are allocated today.

p The formula that the EEC adopted, based on historic catches, is one of most contentious parts of the CFP for the UK. Many fishers have stories of the years running up to 1983, where foreign vessels increased their fishing activity in UK waters in order to secure a larger share of these fish in perpetuity. Although there is little evidence to support these views, it demonstrates the level of distrust in both the system, and foreign fishers, from the outset.

p Como resultado, only 32% of fish caught in the UK EEZ today is caught by UK boats, with most of the remainder taken by vessels from other EU states, Norway and the Faroe Islands (who have also joined the CFP). Portanto, non-UK vessels catch the remaining 68%, cerca de 700, 000 tonnes, of fish a year in the UK EEZ.In return, the UK fleet lands about 92, 000 tonnes a year from other EU countries' waters.

p Joining the CFP did not cause a decline in UK fish landings. Contudo, in its early days, it did nothing to stop it. Fish landings continued to decline – and along with this, the industry itself contracted, using improved technology to offset the decline in stocks. Through the 1980s and into the early part of this century the imbalance – enshrined in the relative stability measure of the CFP – has led to the view that the CFP doesn't work in the UK's interests. Rather it allows the rest of the EU to take advantage of the country's fish stocks.

p The CFP's quota system, while credited for helping the industry survive (and even reverse the collapse in fish stocks), is now seen as burdensome and preventing further growth.

p A recent academic analysis of the current performance of the CFP showed it was not improving the management of the fish stock resources in any of its 17 criteria and was actually making things worse in seven areas.

p Por exemplo, a 2013 reform of the CFP introduced the landing obligation, the so-called "discard ban", that was designed to stop vessels discarding fish (bycatch) caught alongside the species they were targeting. Environmentalists, and campaigns backed by celebrities such as Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, have long voiced concerns over incidents of bycatch being dumped by fishers operating under the quota system.

p This policy is now seen as potentially disastrous by some representatives of Britain's North Sea fishing fleet, as so many different types of fish live in the waters and bycatch is common and often unavoidable. They are concerned that boats would be forced to fill their holds with commercially worthless fish and return to port early. Or by exhausting their quota for some species early in the season, they would be forced to stay in port for the rest of the year, despite having quotas available for other species. Evidence given to the House of Lords suggests that this situation has not arisen as non-compliance and a lack of enforcement has undermined the discard ban.

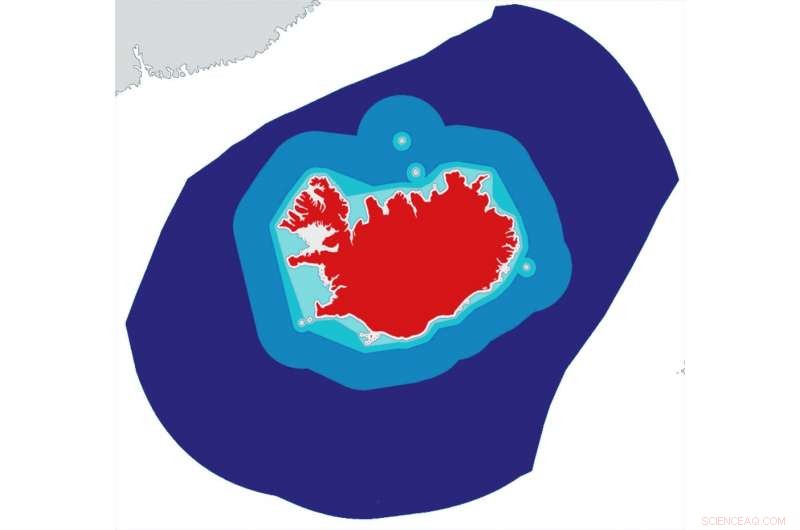

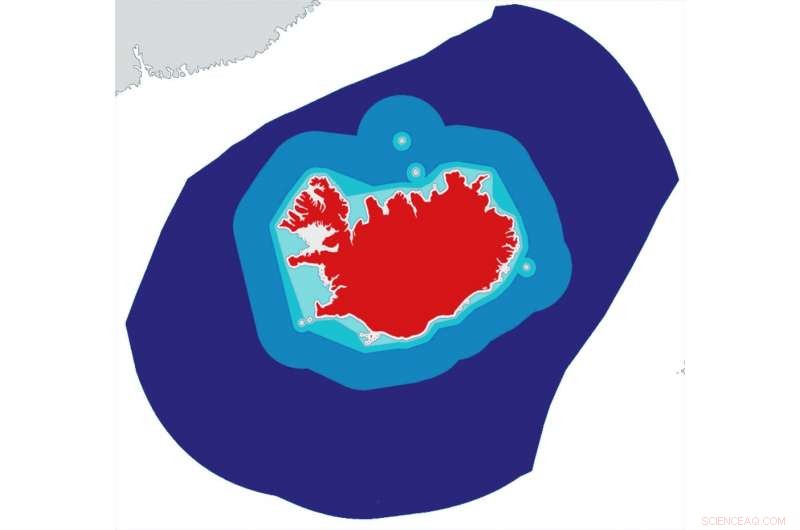

p Map of the Icelandic EEZ, and its expansion. Red =Iceland. White =internal waters. Light turquoise =four-mile expansion, 1952. Dark turquoise =12-mile expansion (current extent of territorial waters), 1958. Blue =50-mile expansion, 1972. Dark blue =200-mile expansion (current extent of EEZ), 1975. Credit:Kjallakr/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

p Map of the Icelandic EEZ, and its expansion. Red =Iceland. White =internal waters. Light turquoise =four-mile expansion, 1952. Dark turquoise =12-mile expansion (current extent of territorial waters), 1958. Blue =50-mile expansion, 1972. Dark blue =200-mile expansion (current extent of EEZ), 1975. Credit:Kjallakr/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

p When we interviewed fishers in north-east Scotland in 2018, we found many feared such blanket management across the entire EU would continue to damage their industry because it simply does not take into account the local environment that they work in.

p

Brexit

p The depth of feeling among the UK fishing community was illustrated by the voting figures for the EU referendum in June 2016.

p In Banff and Buchan, the constituency in Scotland containing Peterhead and Fraserburgh – the largest and third largest fishing ports in the UK respectively – 54% of people voted to leave the EU, with the size of the fishing industry given as the reason for this result. The result compared to 52% for the whole of the UK and just 38% for Scotland. A survey of members of the UK fishing industry before the vote indicated that 92.8% of correspondents believed that doing so would improve the UK fishing industry by some measure.

p But will Brexit really bring the fishing revival so many have promised and hoped for? British politicians have promised a renaissance in UK fishing after leaving the EU. A Fisheries Bill was launched by the environment secretary, Michael Gove, with an aim to "take back control of UK waters". Contudo, no definitive plan to remove the UK from the CFP in a transition deal has been made, nor has the industry been given any answers on future access for EU vessels, the apportionment of any new quota – if indeed the quota system remains as it is – the rules that they will be operating under, or even a date on which this will come into effect.

p The UK government is seen by many in the fishing industry to be acting against their interests in pursuit of wider goals, for example by using the industry as a bargaining chip in wider UK trade negotiations with the EU.

p The fishing industry's distrust of the government has a long tail:many believe they were sacrificed in 1973 by the then prime minister, Edward Heath, in order to secure access to the single market.

p

A soured relationship

p Ironicamente, despite the fishing industry's support for Brexit and the popular campaign promises, our research suggests fishers don't simply want to close British waters to European fleets. We interviewed people who were sympathetic to their fellow fishers from abroad and did not wish to see businesses and livelihoods lost. They favour a re-balancing of quotas over time to allow EU vessels to adapt to the change, with all vessels having to adhere to UK rules. This would avoid any situations similar to the Scallop War by ensuring that all vessels with a quota have to abide by local restrictions.

p The EU is the main export market for UK fish and fisheries products accounting for 70% of UK fisheries exports by value. Valued at £1.3 billion, this trade far exceeds the £980m value of fish landed in the UK, due to the added value from the processing sector. Some of the remaining 30% of exports that go to countries outside of the EU are governed by trade agreements negotiated by the EU that reduce trade barriers. So the single market, and additional trade agreements, are crucial to the success of the UK fishing industry.

p This reliance on trade into the EU puts the industry in a position where unilaterally preventing access to UK waters would likely be met by reciprocal trade barriers and tariffs. This would increase the cost of their product, while reducing access to their biggest market. The question for the government, então, is how to balance a political issue against an economic one?

p The issue centres on the word "control". If the UK has control of its waters that would simply mean that its government has the power to decide on anything from keeping fishing within UK waters purely for UK vessels, to remaining in or re-entering the CFP, or all points in between. Until the deals are negotiated and signed, the industry will remain in a limbo that has reopened old wounds and reignited distrust in the UK government. p Este artigo foi republicado de The Conversation sob uma licença Creative Commons. Leia o artigo original.