Fique bem para trás. Crédito:RHJPhtotoandilustração

Faz um ano desde que a Horizon Nuclear Power, uma empresa de propriedade da Hitachi, confirmou que estava abandonando a construção da usina nuclear Wylfa de £ 20 bilhões em Anglesey, no norte do País de Gales. O conglomerado industrial japonês citou o fracasso em chegar a um acordo de financiamento com o governo do Reino Unido devido aos custos crescentes, e o governo ainda está em negociações com outros players para tentar levar o projeto adiante.

O preço das ações da Hitachi subiu 10% quando anunciou sua retirada, refletindo o sentimento negativo dos investidores em relação à construção de grandes usinas nucleares complexas e altamente regulamentadas. Com os governos relutantes em subsidiar a energia nuclear por causa dos altos custos, principalmente desde o desastre de Fukushima em 2011, o mercado subvalorizou o potencial dessa tecnologia para enfrentar a emergência climática, fornecendo eletricidade de baixo carbono abundante e confiável.

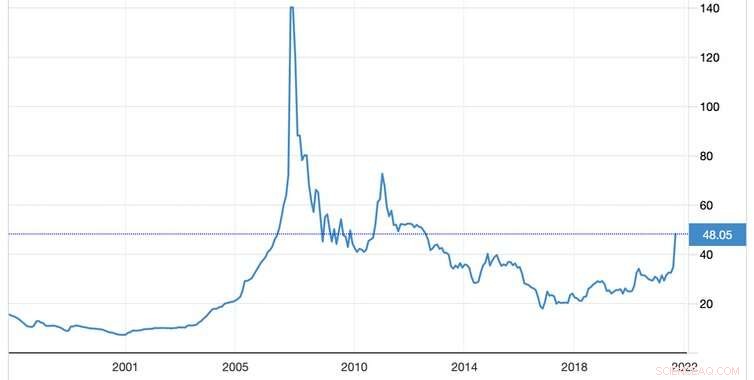

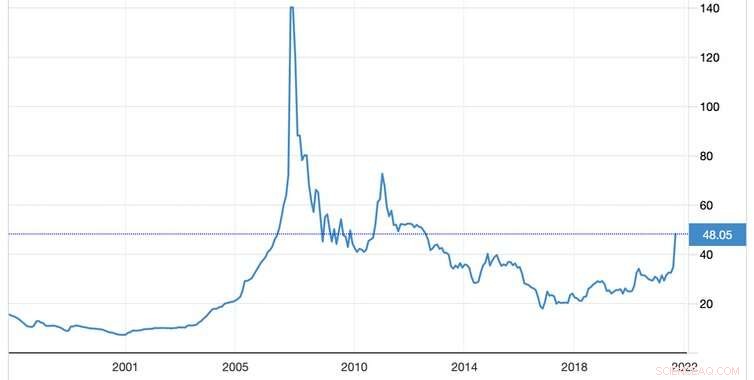

Os preços do urânio refletiram por muito tempo essa realidade. O combustível primário para usinas nucleares estava caindo durante grande parte da década de 2010, sem sinais de uma grande reviravolta. No entanto, desde meados de agosto, os preços subiram cerca de 60% à medida que investidores e especuladores lutam para comprar a commodity. O preço está em torno de US$ 48 por libra (453g), tendo sido tão barato quanto US$ 28,99 em 16 de agosto. Então, o que está por trás desse rali e o que isso significa para a energia nuclear?

Preço do urânio O mercado de urânio A demanda por urânio é limitada à produção de energia nuclear e equipamentos médicos. A demanda global anual é de 150 milhões de libras, com usinas de energia nuclear procurando garantir contratos cerca de dois anos antes do uso.

Embora a demanda de urânio não seja imune a crises econômicas, está menos exposta do que outros metais e commodities industriais. A maior parte da demanda está distribuída em cerca de 445 usinas nucleares operando em 32 países, com oferta concentrada em algumas minas. O Cazaquistão é facilmente o maior produtor com mais de 40% da produção, seguido pela Austrália (13%) e Namíbia (11%).

Como a maior parte do urânio extraído é usado como combustível por usinas nucleares, seu valor intrínseco está intimamente ligado à demanda atual e ao potencial futuro dessa indústria. O mercado inclui não apenas consumidores de urânio, mas também especuladores, que compram quando acham que o preço está barato, potencialmente aumentando o preço. Um desses especuladores de longo prazo é o Sprott Physical Uranium Trust, com sede em Toronto, que comprou quase 6 milhões de libras (ou US$ 240 milhões) de urânio nas últimas semanas.

Por que o otimismo dos investidores pode estar aumentando Embora se acredite amplamente que a energia nuclear deva desempenhar um papel fundamental na transição para a energia limpa, os altos custos tornaram-na pouco competitiva em comparação com outras fontes de energia. Mas graças aos fortes aumentos nos preços da energia, a competitividade da energia nuclear está melhorando. Também estamos vendo um maior compromisso com novas usinas nucleares da China e de outros lugares. Enquanto isso, tecnologias nucleares inovadoras, como pequenos reatores modulares (SMRs), que estão sendo desenvolvidos em países como China, EUA, Reino Unido e Polônia, prometem reduzir os custos iniciais de capital.

Crédito:Economia Comercial

Combined with recent optimistic releases about nuclear power from the World Nuclear Association and the International Atomic Energy Agency (the IAEA upped its projections for future nuclear-power use for the first time since Fukushima) this is all making investors more bullish about future uranium demand.

The effect on the price has also been multiplied by issues on the supply side. Due to the previously low prices, uranium mines around the world have been mothballed for several years. For example, Cameco, the world's largest listed uranium company, suspended production at its McArthur River mine in Canada in 2018.

Global supply was further hit by COVID-19, with production falling by 9.2% in 2020 as mining was disrupted. At the same time, since uranium has no direct substitute, and is involved with national security, several countries including China, India and the US have amassed large stockpiles—further limiting available supply.

Hang on tight When you compare the cost of producing electricity over the lifetime of a power station, the cost of uranium has a much smaller impact on a nuclear plant than the equivalent effect of, say, gas or biomass:it's 5% compared to around 80% in the others. As such, a big rise in the price of uranium will not massively affect the economics of nuclear power.

Yet there is certainly a risk of turbulence in this market over the months ahead. In 2021, markets for the likes of Gamestop and NFTs have become iconic examples of speculative interest and irrational exuberance—optimism driven by mania rather than a sober evaluation of the economic fundamentals.

The uranium price surge also appears to be catching the attention of transient investors. There are indications that shares in companies and funds (like Sprott) exposed to uranium are becoming meme stocks for the r/WallStreetBets community on Reddit. Irrational exuberance may not have explained the initial surge in uranium prices, but it may mean more volatility to come.

We could therefore see a bubble in the uranium market, and don't be surprised if it is followed by an over-correction to the downside. Because of the growing view that the world will need significantly more uranium for more nuclear power, this will likely incentivise increased mining and the release of existing reserves to the market. In the same way as supply issues have exacerbated the effect of heightened demand on the price, the same thing could happen in the opposite direction when more supply becomes available.

You can think of all this as symptomatic of the current stage in the uranium production cycle:a glut of reserves has suppressed prices too low to justify extensive mining, and this is being followed by a price surge which will incentivise more mining. The current rally may therefore act as a vital step to ensuring the next phase of the nuclear power industry is adequately fuelled.

Amateur traders should be careful not to get caught on the wrong side of this shift. But for a metal with a half life of 700 million years, serious investors can perhaps afford to wait it out.