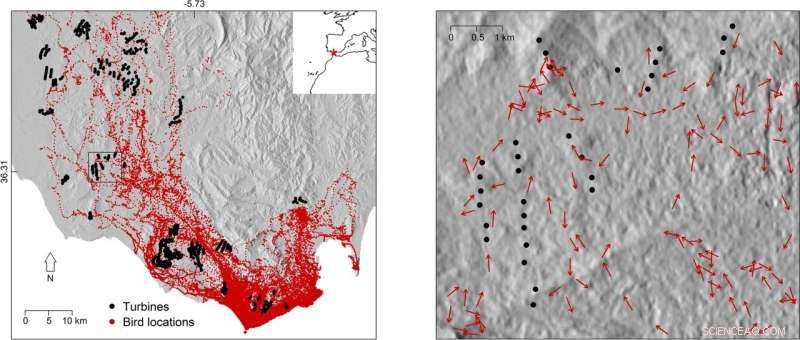

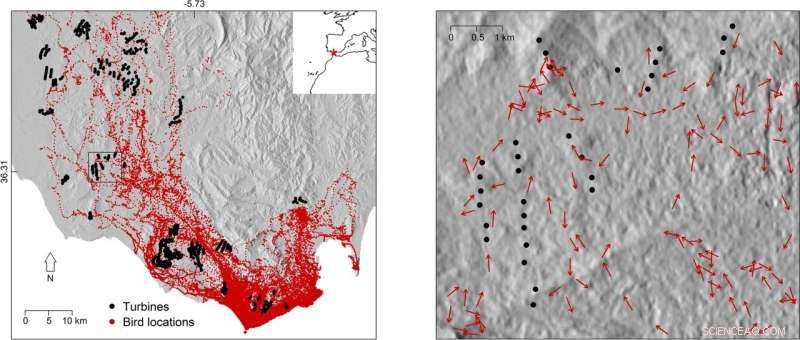

O painel esquerdo mostra a distribuição espacial das localizações de aves e turbinas na área de estudo entre Cádiz e Tarifa (sul da Espanha). O asterisco vermelho no canto superior direito marca a localização da área de estudo. O painel direito mostra os rumos do voo dos pássaros em comparação com os locais das turbinas em uma pequena seção da área de estudo (quadrado no painel esquerdo). O sombreamento das colinas foi adicionado como pano de fundo para ilustrar a interação entre o uso do espaço das aves e a topografia. Os dados usados para ilustrar o sombreamento de colinas foram recuperados de um modelo de elevação digital disponível publicamente (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov). Crédito:Relatórios Científicos (2022). DOI:10.1038/s41598-022-10295-9

Na corrida para evitar a mudança climática descontrolada, duas tecnologias de energia renovável estão sendo promovidas como a solução para alimentar as sociedades humanas:a eólica e a solar. Mas por muitos anos, as turbinas eólicas estiveram em rota de colisão com a conservação da vida selvagem. Aves e outros animais voadores correm o risco de morrer por impacto com as pás do rotor das turbinas, levantando questões sobre a viabilidade do vento como pedra angular de uma política global de energia limpa. Agora, um par de estudos de rastreamento de animais do Instituto Max Planck de Comportamento Animal e da Universidade de East Anglia, no Reino Unido, forneceu dados detalhados de GPS sobre o comportamento de voo de pássaros suscetíveis à colisão com a infraestrutura de energia. O primeiro, um estudo em larga escala de 1.454 aves de 27 espécies, identificou pontos críticos na Europa onde as aves estão particularmente em risco devido a turbinas eólicas e linhas de energia. A segunda abordou como os pássaros se comportam ao voar perto de turbinas, revelando que os indivíduos evitarão ativamente as turbinas se estiverem a menos de um quilômetro. Ao rastrear o movimento das aves com dispositivos GPS de alta precisão, ambos os estudos fornecem os dados biológicos detalhados necessários para expandir a infraestrutura de energia renovável com impactos mínimos à vida selvagem.

A geração de energia eólica vem aumentando nas últimas duas décadas com o compromisso global de transição para energia renovável a partir de combustíveis fósseis emissores de carbono. A capacidade de energia eólica terrestre europeia deverá crescer quase quatro vezes até 2050, e países do Oriente Médio e Norte da África, como Marrocos e Tunísia, também têm metas para aumentar a participação no fornecimento de eletricidade a partir do vento onshore.

"Sabemos de pesquisas anteriores que existem muito mais locais adequados para construir turbinas eólicas do que precisamos para cumprir nossas metas de energia limpa até 2050", disse o principal autor Jethro Gauld, Ph.D. researcher in the School of Environmental Sciences at University of East Anglia. "If we can do a better job of assessing risks to biodiversity, such as collision risk for birds, into the planning process at an early stage we can help limit the impact of these developments on wildlife while still achieving our climate targets."

Pinpointing collision hotspots in Europe An international team of 51 researchers from 15 countries, including the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior in Germany, collaborated to identify the areas where these birds would be more sensitive to onshore wind turbine or power line development. The study, published in

Journal of Applied Ecology , used GPS location data from 65 bird tracking studies to understand where they fly more frequently at danger height—defined as 10 to 60 meters above ground for power lines and 15 to 135 meters for wind turbines. "GPS tracking provides very accurate data on location and flight height, which cannot be obtained from direct observation, particularly from large distances," says Martin Wikelski, director at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior and co-author on the study. "This study represents the first time GPS data from so many species has been pooled to create a comprehensive picture of where birds are at risk.

The resulting vulnerability maps reveal that the collision hotspots are particularly concentrated within important migration routes, along coastlines and near breeding locations. These include the Western Mediterranean coast of France, Southern Spain and the Moroccan Coast—such as around the Strait of Gibraltar—Eastern Romania, the Sinai Peninsula and the Baltic coast of Germany. The GPS data collected related to 1,454 birds from 27 species, mostly large soaring ones such as white storks. Exposure to risk varied across the species, with the Eurasian spoonbill, European eagle owl, whooper swan, Iberian imperial eagle and white stork among those flying consistently at heights where they risk collision. The authors say development of new wind turbines and transmission power lines should be minimized in these high sensitivity areas, and any developments which do occur will likely need to be accompanied by measures to reduce the risk to birds.

How birds behave near turbines As well as providing location and flight height, GPS loggers open up an additional frontier in efforts to better plan energy infrastructure. "With GPS tracking we are able to understand exactly how birds behave as they fly close to the turbines," says Carlos Santos, an Affiliated Scientist of the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior and an Assistant Professor at the Federal University of Pará, in Brazil. "Knowing how close they fly, and whether or not wind or other factors influence their flight behavior, is very important to mitigate collision rates as it can help better planning of wind farms."

A team of scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior and the University of East Anglia focused their attention on the black kite, a very common soaring bird that migrates through the Strait of Gibraltar, the narrow straight between southern Spain and North Africa. "The Strait of Gibraltar is the main migratory bottleneck for birds in western Europe but it's also a hotspot for wind farms," says Santos. "We wanted to see how soaring birds behave in this area, which represent a serious threat during their migration to Africa."

This study, published in

Scientific Reports , looked at GPS information from 126 black kites as the birds approached wind turbines. The data showed that birds avoided flight paths straight to turbines as they flew closer to them. The birds started to deviate from turbines one kilometer away, but this effect was even more pronounced within 750 meters and when the wind was blowing towards the turbines. "This means that they recognize the risk of the turbines and keep a safe distance from them," says Santos.

The authors say collecting GPS data from the interaction between birds and turbines is extremely difficult. Says Santos:"You need to tag many animals to increase the chances of recording their behavior near the turbines. This is why our dataset is so uncommon. Fortunately, GPS tracking studies are becoming more common and hopefully in the near future we will be able to gather data of this sort for other soaring bird species." The authors stress that understanding how the birds perceive wind turbines and which factors attenuate or exacerbate their perception is critical to learn where to place turbines and to develop effective deterrents.