Os antigos maias eram um conto de advertência agrícola? Talvez não, sugere um novo estudo

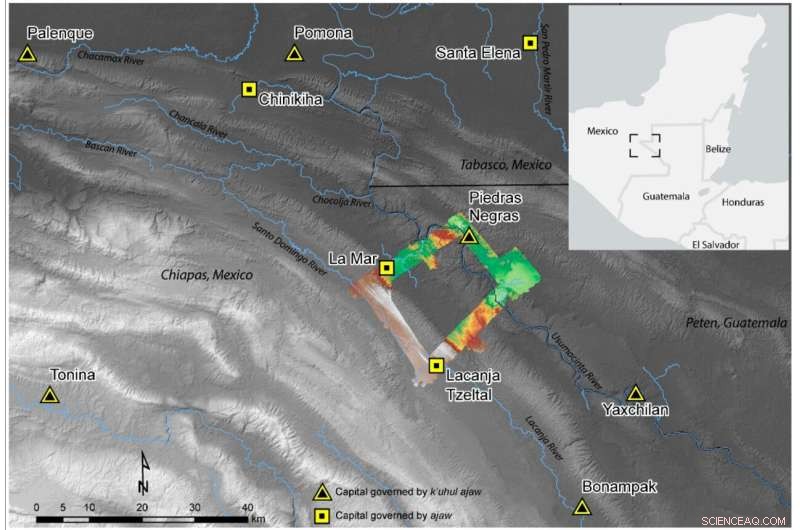

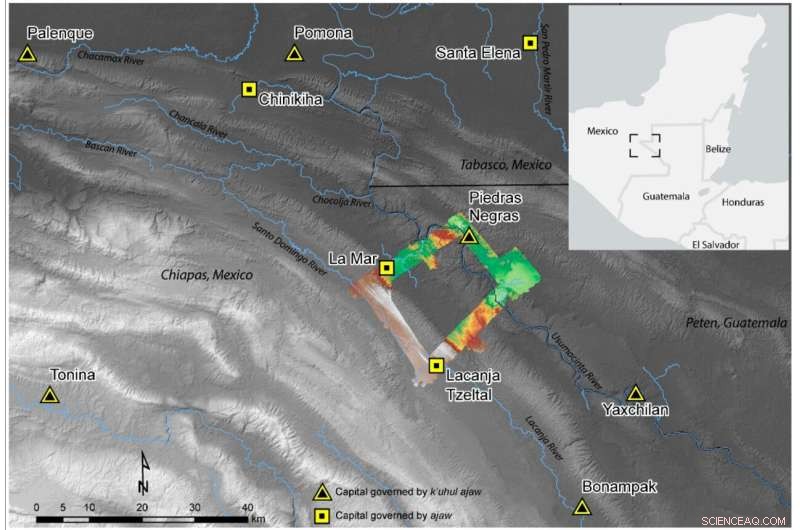

A equipe de pesquisa pesquisou uma pequena área nas planícies maias ocidentais situadas na fronteira de hoje entre o México e a Guatemala, mostrada no contexto aqui. Crédito:Andrew Scherer/Brown University

Muitos acreditam que as mudanças climáticas e a degradação ambiental causaram a queda da civilização maia, mas uma nova pesquisa mostra que alguns reinos maias tiveram práticas agrícolas sustentáveis e alta produção de alimentos por séculos.

Durante anos, especialistas em ciência do clima e ecologia sustentaram as práticas agrícolas dos antigos maias como os principais exemplos do que não fazer.

“Há uma narrativa que retrata os maias como pessoas que se engajaram no desenvolvimento agrícola descontrolado”, disse Andrew Scherer, professor associado de antropologia da Brown University. "A narrativa é:a população cresceu muito, a agricultura cresceu e então tudo desmoronou."

Mas um novo estudo, de autoria de Scherer, alunos da Brown e acadêmicos de outras instituições, sugere que essa narrativa não conta a história completa.

Usando drones e lidar, uma tecnologia de sensoriamento remoto, uma equipe liderada por Scherer e Charles Golden, da Brandeis University, pesquisou uma pequena área nas planícies maias ocidentais, situada na atual fronteira entre o México e a Guatemala. A pesquisa Lidar de Scherer – e, mais tarde, a pesquisa com botas no chão – revelou extensos sistemas de irrigação e terraços sofisticados dentro e fora das cidades da região, mas nenhum boom populacional enorme para igualar. As descobertas demonstram que entre 350 e 900 d.C., alguns reinos maias viviam confortavelmente, com sistemas agrícolas sustentáveis e nenhuma insegurança alimentar demonstrada.

“É emocionante falar sobre as populações realmente grandes que os maias mantinham em alguns lugares; sobreviver por tanto tempo com tal densidade foi uma prova de suas realizações tecnológicas”, disse Scherer. "Mas é importante entender que essa narrativa não se traduz em toda a região maia. As pessoas nem sempre viviam lado a lado. Algumas áreas que tinham potencial para o desenvolvimento agrícola nunca foram ocupadas."

As descobertas do grupo de pesquisa foram publicadas na revista

Remote Sensing .

Quando a equipe de Scherer embarcou na pesquisa lidar, eles não estavam necessariamente tentando desmascarar suposições de longa data sobre as práticas agrícolas maias. Em vez disso, sua principal motivação era aprender mais sobre a infraestrutura de uma região relativamente pouco estudada. Enquanto algumas partes da área maia ocidental são bem estudadas, como o conhecido local de Palenque, outras são menos compreendidas, devido ao denso dossel tropical que há muito esconde as comunidades antigas da vista. Não foi até 2019, de fato, que Scherer e seus colegas descobriram o reino de Sak T'zi", que os arqueólogos tentavam encontrar há décadas.

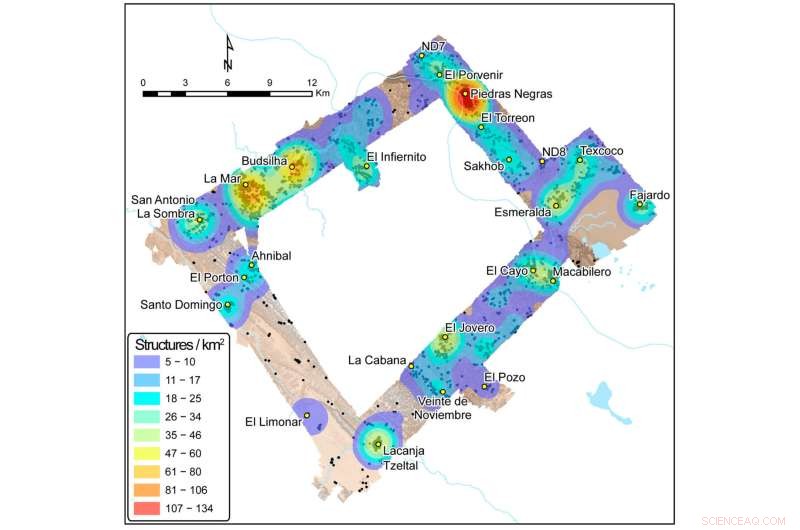

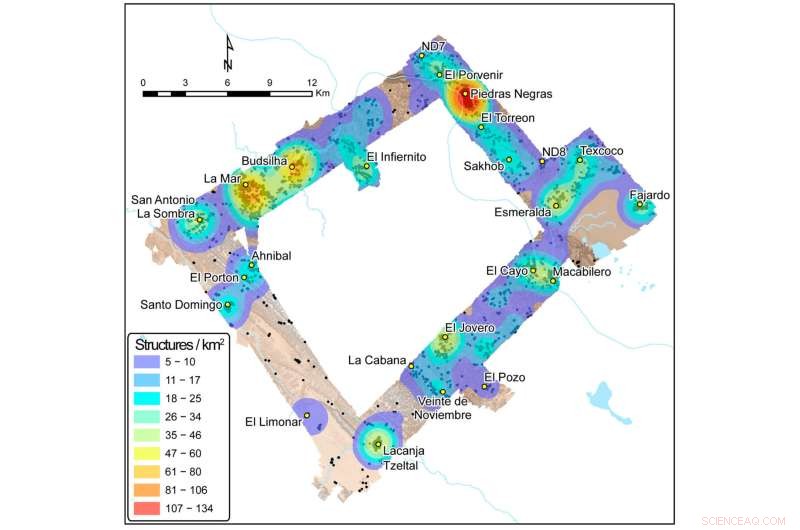

As varreduras do Lidar da área de pesquisa revelaram a densidade relativa de estruturas em Piedras Negras, La Mar e Lacanjá Tzeltal, fornecendo dicas sobre as respectivas populações e necessidades alimentares dessas cidades. Crédito:Brown University

A equipe escolheu pesquisar um retângulo de terra que liga três reinos maias:Piedras Negras, La Mar e Sak Tz'i", cuja capital política estava centrada no sítio arqueológico de Lacanjá Tzeltal. Em moscas de corvo, esses três centros urbanos tinham tamanhos populacionais e poder de governo muito diferentes, disse Scherer.

"Hoje, o mundo tem centenas de estados-nação diferentes, mas eles não são realmente iguais uns aos outros em termos de influência que têm no cenário geopolítico", disse Scherer. "Isso é o que vemos no império maia também."

Scherer explicou que todos os três reinos eram governados por um ajaw, ou um senhor – posicionando-os como iguais, em teoria. But Piedras Negras, the largest kingdom, was led by a k'uhul ajaw, a "holy lord," a special honorific not claimed by the lords of La Mar and Sak Tz'i." La Mar and Sak Tz'i' weren't exactly equal peers, either:While La Mar was much more populous than the Sak T'zi' capital Lacanjá Tzeltal, the latter was more independent, often switching alliances and never appearing to be subordinate to other kingdoms, suggesting it had greater political autonomy.

The lidar survey showed that despite their differences, these three kingdoms boasted one major similarity:Agriculture that yielded a food surplus.

"What we found in the lidar survey points to strategic thinking on the Maya's part in this area," Scherer said. "We saw evidence of long-term agricultural infrastructure in an area with relatively low population density—suggesting that they didn't create some crop fields late in the game as a last-ditch attempt to increase yields, but rather that they thought a few steps ahead."

In all three kingdoms, the lidar revealed signs of what the researchers call "agricultural intensification"—the modification of land to increase the volume and predictability of crop yields. Agricultural intensification methods in these Maya kingdoms, where the primary crop was maize, included building terraces and creating water management systems with dams and channeled fields. Penetrating through the often-dense jungle, the lidar showed evidence of extensive terracing and expansive irrigation channels across the region, suggesting that these kingdoms were not only prepared for population growth but also likely saw food surpluses every year.

"It suggests that by the late Classic Period, around 600 to 800 A.D., the area's farmers were producing more food than they were consuming," Scherer said. "It's likely that much of the surplus food was sold at urban marketplaces, both as produce and as part of prepared foods like tamales and gruel, and used to pay tribute, a tax of sorts, to local lords."

Scherer said he hopes the study provides scholars with a more nuanced view of the ancient Maya—and perhaps even offers inspiration for members of the modern-day agricultural sector who are looking for sustainable ways to grow food for an ever-growing global population. Today, he said, significant parts of the region are being cleared for cattle ranching and palm oil plantations. But in areas where people still raise corn and other crops, they report that they have three harvests a year—and it's likely that those high yields may be due in part to the channeling and other modifications that the ancient Maya made to the landscape.

"In conversations about contemporary climate or ecological crises, the Maya are often brought up as a cautionary tale:"They screwed up; we don't want to repeat their mistakes,'" Scherer said. "But maybe the Maya were more forward-thinking than we give them credit for. Our survey shows there's a good argument to be made that their agricultural practices were very much sustainable."