Hoje as ondas de calor parecem muito mais quentes do que o índice de calor indica

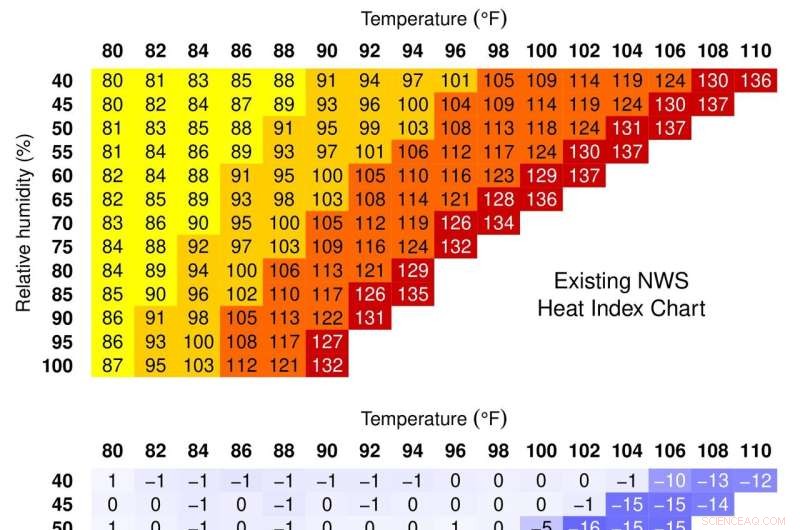

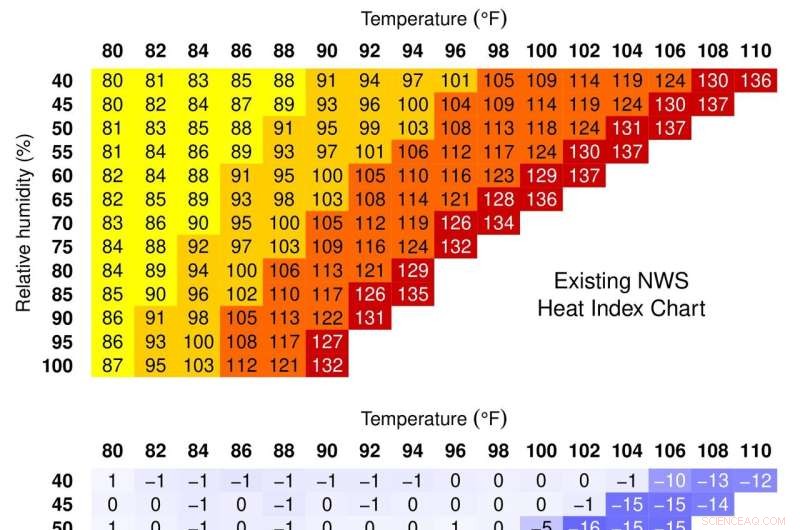

A tabela de Índice de Calor (topo) usada há muito tempo subestima a temperatura aparente para as condições mais extremas de calor e umidade que ocorrem hoje (centro). A versão corrigida (abaixo) é precisa em toda a faixa de temperaturas e umidades que os humanos encontrarão com as mudanças climáticas. Crédito:David Romps e Yi-Chuan Lu, UC Berkeley

Se você olhou para o índice de calor durante as ondas de calor pegajosas deste verão e pensou:"Com certeza está mais quente", você pode estar certo.

Uma análise feita por cientistas climáticos da Universidade da Califórnia, em Berkeley, descobriu que a temperatura aparente, ou índice de calor, calculado por meteorologistas e pelo Serviço Nacional de Meteorologia (NWS) para indicar a sensação de calor – levando em consideração a umidade – subestima a percepção temperatura para os dias mais sufocantes que estamos experimentando agora, às vezes em mais de 20 graus Fahrenheit.

A descoberta tem implicações para quem sofre com essas ondas de calor, já que o índice de calor é uma medida de como o corpo lida com o calor quando a umidade é alta, e a transpiração se torna menos eficaz para nos resfriar. Sudorese e rubor – onde o sangue é desviado para capilares próximos à pele para dissipar o calor – e trocar de roupa são as principais maneiras pelas quais os humanos se adaptam às temperaturas quentes.

Um índice de calor mais alto significa que o corpo humano fica mais estressado durante essas ondas de calor do que as autoridades de saúde pública podem perceber, dizem os pesquisadores. O NWS atualmente considera um índice de calor acima de 103 perigoso e acima de 125 extremamente perigoso.

"Na maioria das vezes, o índice de calor que o Serviço Nacional de Meteorologia está fornecendo é o valor certo. É apenas nesses casos extremos que eles estão obtendo o número errado", disse David Romps, professor de Terra e Planetas da UC Berkeley. Ciência. “O que importa é quando você começa a mapear o índice de calor de volta aos estados fisiológicos e percebe, oh, essas pessoas estão sendo estressadas com uma condição de fluxo sanguíneo da pele muito elevado, onde o corpo está quase ficando sem truques para compensar. para esse tipo de calor e umidade. Então, estamos mais perto desse limite do que pensávamos estar antes."

Romps e o estudante de pós-graduação Yi-Chuan Lu detalharam sua análise em um artigo aceito pela revista

Environmental Research Letters e postado on-line em 12 de agosto.

O índice de calor foi criado em 1979 por um físico têxtil, Robert Steadman, que criou equações simples para calcular o que ele chamou de "sensação" relativa de condições quentes e úmidas, bem como quentes e áridas durante o verão. Ele viu isso como um complemento ao fator de resfriamento do vento comumente usado no inverno para estimar a sensação de frio.

Seu modelo levou em consideração como os humanos regulam sua temperatura interna para obter conforto térmico sob diferentes condições externas de temperatura e umidade – alterando conscientemente a espessura das roupas ou ajustando inconscientemente a respiração, a transpiração e o fluxo sanguíneo do núcleo do corpo para a pele.

Em seu modelo, a temperatura aparente sob condições ideais - uma pessoa de tamanho médio na sombra com água ilimitada - é o quão quente alguém sentiria se a umidade relativa estivesse em um nível confortável, que Steadman considerou uma pressão de vapor de 1.600 pascal .

Por exemplo, a 70% de umidade relativa e 68 F - que geralmente é tomada como umidade e temperatura médias - uma pessoa sentiria 68 F. Mas na mesma umidade e 86 F, pareceria 94 F.

The heat index has since been adopted widely in the United States, including by the NWS, as a useful indicator of people's comfort. But Steadman left the index undefined for many conditions that are now becoming increasingly common. For example, for a relative humidity of 80%, the heat index is not defined for temperatures above 88 F or below 59 F. Today, temperatures routinely rise above 90 F for weeks at a time in some areas, including the Midwest and Southeast.

To account for these gaps in Steadman's chart, meteorologists extrapolated into these areas to get numbers, Romps said, that are correct most of the time, but not based on any understanding of human physiology.

"There's no scientific basis for these numbers," Romps said.

He and Lu set out to extend Steadman's work so that the heat index is accurate at all temperatures and all humidities between zero and 100%.

"The original table had a very short range of temperature and humidity and then a blank region where Steadman said the human model failed," Lu said. "Steadman had the right physics. Our aim was to extend it to all temperatures so that we have a more accurate formula."

One condition under which Steadman's model breaks down is when people perspire so much that sweat pools on the skin. At that point, his model incorrectly had the relative humidity at the skin surface exceeding 100%, which is physically impossible.

"It was at that point where this model seems to break, but it's just the model telling him, hey, let sweat drip off the skin. That's all it was," Romps said. "Just let the sweat drop off the skin."

That and a few other tweaks to Steadman's equations yielded an extended heat index that agrees with the old heat index 99.99% of the time, Romps said, but also accurately represents the apparent temperature for regimes outside those Steadman originally calculated. When he originally published his apparent temperature scale, he considered these regimes too rare to worry about, but high temperatures and humidities are becoming increasingly common because of climate change.

Romps and Lu had published the revised heat index equation earlier this year. In the most recent paper, they apply the extended heat index to the top 100 heat waves that occurred between 1984 and 2020. The researchers find mostly minor disagreements with what the NWS reported at the time, but also some extreme situations where the NWS heat index was way off.

One surprise was that seven of the 10 most physiologically stressful heat waves over that time period were in the Midwest—mostly in Illinois, Iowa and Missouri—not the Southeast, as meteorologists assumed. The largest discrepancies between the NWS heat index and the extended heat index were seen in a wide swath, from the Great Lakes south to Louisiana.

During the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago, for example, which killed at least 465 people, the maximum heat index reported by the NWS was 135 F, when it actually felt like 154 F. The revised heat index at Midway Airport, 141 F, implies that people in the shade would have experienced blood flow to the skin that was 170% above normal. The heat index reported at the time, 124 F, implied only a 90% increase in skin blood flow. At some places during the heat wave, the extended heat index implies that people would have experienced an increase of 820% above normal skin blood flow.

"I'm no physiologist, but a lot of things happen to the body when it gets really hot," Romps said. "Diverting blood to the skin stresses the system because you're pulling blood that would otherwise be sent to internal organs and sending it to the skin to try to bring up the skin's temperature. The approximate calculation used by the NWS, and widely adopted, inadvertently downplays the health risks of severe heat waves."

Physiologically, the body starts going haywire when the skin temperature rises to equal the body's core temperature, typically taken as 98.6 F. After that, the core temperature begins to increase. The maximum sustainable core temperature is thought to be 107 F—the threshold for heat death. For the healthiest of individuals, that threshold is reached at a heat index of 200 F.

Luckily, humidity tends to decrease as temperature increases, so Earth is unlikely to reach those conditions in the next few decades. Less extreme—though still deadly—conditions are nevertheless becoming common around the globe.

"A 200 F heat index is an upper bound of what is survivable," Romps said. "But now that we've got this model of human thermoregulation that works out at these conditions, what does it actually mean for the future habitability of the United States and the planet as a whole? There are some frightening things we are looking at."

+ Explorar mais Hot and getting hotter:Five essential reads on high temps and human bodies