Quando os fósseis ganham vida:pico de SARS-CoV-2, sincitina-1 e outras proteínas de fusão curiosas

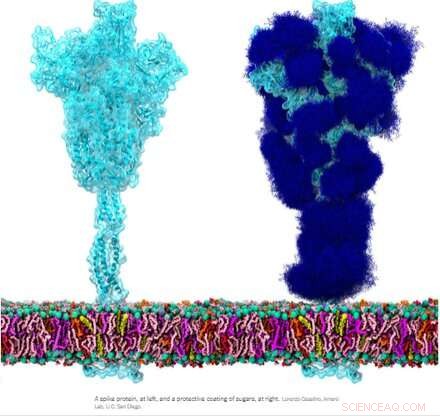

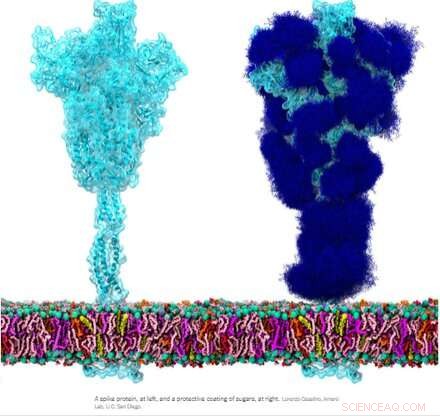

Crédito:Wikipédia

A glicoproteína de pico homotrimérica (S) do SARS-CoV-2, particularmente sua subunidade S2, é uma proteína de fusão extraordinária. Ele pode fundir partículas virais a células e também fundir células a células para criar vários sincícios entre diferentes fenótipos celulares. Dependendo de quais versões exatas estão sendo consideradas, o spike pode realizar essas façanhas por meio de vários mecanismos que atuam nos lados intracelular e extracelular das membranas celulares.

Essas funções de fusão são um tanto análogas às proteínas ENV (envelope) homotriméricas típicas, como nossa proteína ENV retroviral endógena sincitina-1 e a glicoproteína GP160 ENV do vírus HIV. GP160, a proteína 'spike' do HIV, é finalmente processada em seu próprio local de clivagem de furina (também encontrado na sincitina-1) em uma proteína GP120 e GP41, ambas as quais podem adotar configurações pré e pós-fusão distintas. O genoma do SARS-CoV-2, no entanto, já especifica uma pequena proteína ENV separada (convenientemente designada como E), que se monta em um canal de cátions presumido com um poro de fusão central.

Não há genes env, pol, gag ou pro definidos como tal para o genoma do SARS-CoV-2, como é o caso dos retrovírus, que devem se integrar ao nosso DNA como parte de seu ciclo de vida. Curiosamente, os pesquisadores descobriram que a proteína spike SARS-CoV-2, se comportando por conta própria, participa diretamente da ativação de retrovírus endógenos em nossas células, o que contribui para a patologia observada. O que exatamente está acontecendo aqui?

À luz de algumas dessas semelhanças, foi sugerido que os anticorpos gerados contra a proteína spike poderiam potencialmente reagir de forma cruzada em qualquer tecido que pudesse expressar proteínas retrovirais endógenas. Em particular, durante a gravidez, quando os trofoblastos placentários expressam proteínas ENV muito úteis de muitos desses HERVs, incluindo ERVW1 (sincitina-1), ERVFRD-1 (sincitina-2), ERVV-1, ERVV-2, ERVH48-1, ERVMER34-1 , ERV3-1 e ERVK13-1. A expressão de sincitina-2 em citotrofoblastos vilosos, no entanto, está altamente correlacionada com o grau de gravidade de algumas patologias placentárias como a pré-eclâmpsia.

Felizmente, os pesquisadores descobriram que praticamente não há homologia de sequência direta entre spike e sincitina-1, e pouca chance de reatividade cruzada. Escrevendo na revista

Animal Cells and Systems , pesquisadores coreanos testaram um grande painel de anticorpos monoclonais e conseguiram concluir que, embora antigas relíquias genômicas como HERVs possam ser ativadas em vários tecidos pelo SARS-CoV-2, não há risco de reatividade cruzada ou mesmo infertilidade.

Mas se a proteína spike ainda é muito capaz de causar fusão celular indesejável, como podemos definir melhor essa atividade aparentemente aleatória e, além disso, o que podemos fazer a respeito? Talvez o primeiro passo seja ficar um pouco mais sofisticado com a terminologia de fusão celular. Escrevendo no jornal

Oncotarget , o autor Yuri Lazebnik oferece algumas reflexões. Um sincício produzido a partir de células do mesmo tipo, por exemplo, como na fusão de dois ou mais pneumócitos, é denominado homocário. Um heterocário, então, seria um sincício feito de, digamos, um pneumócito fundido a um progenitor epitelial, ou talvez um leucócito. Em geral, uma vez que as células se combinam, todas as apostas estão erradas – se elas podem se classificar mais tarde e seus núcleos para gerar descendentes mononucleares competentes para replicação ainda não é totalmente conhecido.

A formação de sincícios induzidos por picos nos pulmões de pacientes com COVID-10 foi encontrada em muitas formas, cada uma com suas próprias propriedades emergentes que podem contribuir para as sequelas da doença. For example, ciliated cells in the airway, alveolar type 2 pneumocytes, and epithelial progenitors have all been found to participate in the oft-observed multinucleated 'giant cells.' Throw in a spike-laden leukocyte or two and things rapidly get hard to predict. Perhaps an even more alarming situation would be formation of a syncytium in the cells lining our blood vessels that could contribute to thrombosis. The ensuing death and eventual sloughing off of a patch of inappropriately fused cells could expose a sizeable region of thrombogenic basement membrane. A 20-micron fiber of collagen, the main component of the basement membrane, is sufficient to trigger platelet-dependent clotting.

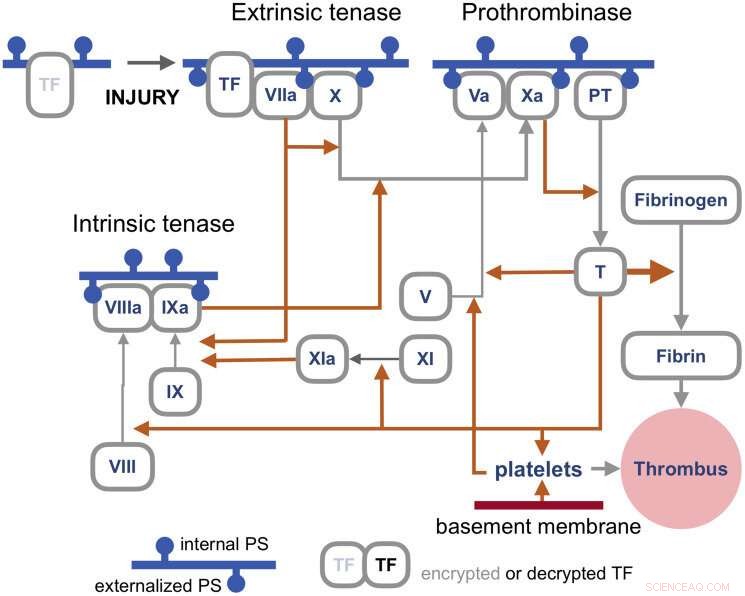

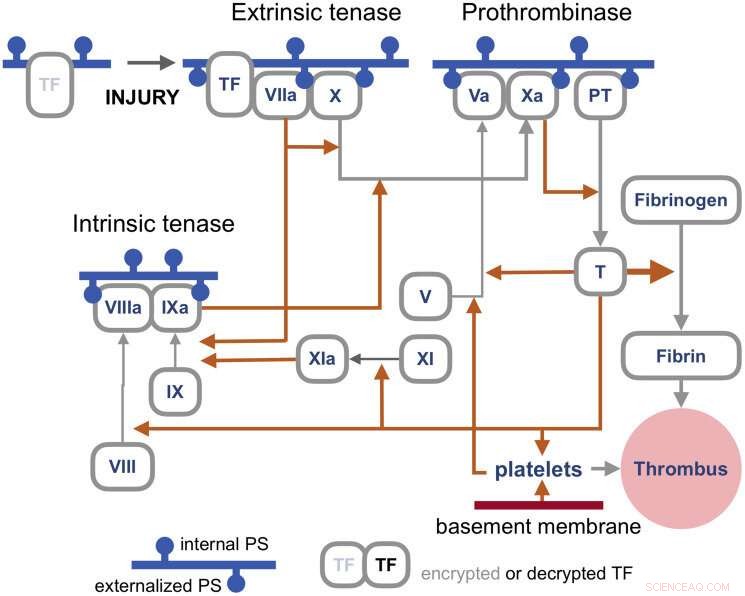

But enough of this fear-mongering. Researchers have identified a set of already approved drugs that prevent spike-induced cell fusion and inhibit TMEM16F, a critical protein for syncytium formation. TMEM16F has the dual role of being a calcium-activated ion channel that regulates chloride secretion, as well as a lipid scramblase that relocates phosphatidylserine (PS) to the cell surface. This PS externalization is required for cell fusion in many systems, including spike-induced syncytia. Incidentally, scramblases also control the rate-limiting steps of the blood coagulation cascade, and may be the mechanism behind spike-induced thrombosis.

The blood coagulation pathways are a whole separate complex can of worms, but suffice it to say here that the primary trigger of coagulation induced by viral infections is the so-called extrinsic 'tenase.' Tenases are enzymes that process Factor X, or FX, (hence ten-ase), in the Tissue Factor (TF) activation pathway, which essentially act as the fuse for thrombus generation. The resulting complexes are assembled on externalized PS in the presence of calcium ions. TF is, in a sense, encrypted and so is unable to activate its downstream target factor FVIIa until it is de-encrypted by externalized PS.

Coagulation pathways. Credit:Y. Lazebnik 2021

The realization that some fusogenic viral, or even retroviral proteins, which are fortuitously expressed in particular regions of the body may likely contribute to thrombotic events is of tremendous practical importance. One need look no further than Moderna's ample proposed pipeline for therapeutic mRNA-delivered amenities based on these proteins for all manner of viral insults to have some pause for inspection. There is certainly no shortage of methods currently employed for building antigenic spike proteins for vaccinations. Depending of how much of the spike code is used, which cleavage sequences are included, and which parts are stabilized, very different proteins can be made. It is probably fair to say that full-length spikes in large questionable vectors or inactivated viral particles have been largely de-emphasized in favor of smaller but more immunogenic concoctions.

Lungs and blood vessels are certainly critical areas of concern in any SARS-CoV-2 infection, but what our precious neurons—can spike fuse them as well? Clearly it can fuse neurons in brain organoids, but then again, what can't researchers do with these instant research publication miracles. In looking more braodly at other kinds of viruses, the fusion of neurons, glial cells, and even axons seems to be par for the course in causing a myriad constellation of potential neurological issues. For example, the pseudorabies virus bridges synapses to electrically couple the activity of neurons by fusing their axons. Fusions with glia have similarly been detected and linked with lasting neuropathic pain after the acute phase of herpes zoster (shingles). As of this Wednesday, we all are further aware that SARS-CoV-2 can utilize the protein vimentin as a way to infect endothelial cells. It should escape no one's notice, or at least that of the neuroscientists, that vimentin is the prime marker used for identifying glial cells.

Additionally, the rapidly expanding body of work looking at endogenous retrovirus re-activation in neurodegenerative disease further suggests to the rational mind that cell fusion may also be involved in this kind of pathology.