Os dinossauros machos e fêmeas eram diferentes? Uma nova técnica estatística está ajudando a responder à pergunta

Como os pesquisadores podem dizer se os dinossauros machos e fêmeas, como o estegossauro, eram diferentes? Crédito:Susannah Maidment et al. &Museu de História Natural, Londres, CC BY

Na maioria das espécies animais, machos e fêmeas diferem. Isso é verdade para pessoas e outros mamíferos, assim como muitas espécies de pássaros, peixes e répteis. Mas e os dinossauros? Em 2015, propus que a variação encontrada nas placas traseiras icônicas dos dinossauros estegossauros se devia a diferenças sexuais.

Fiquei surpreso com o quanto alguns de meus colegas discordaram, argumentando que as diferenças entre os sexos, chamadas de dimorfismo sexual, não existiam nos dinossauros.

Sou paleontólogo, e o debate desencadeado pelo meu artigo de 2015 me fez reconsiderar como os pesquisadores que estudam animais antigos usam estatísticas.

O registro fóssil limitado torna difícil declarar se um dinossauro era sexualmente dimórfico. Mas eu e alguns outros em meu campo estão começando a se afastar do pensamento estatístico tradicional em preto ou branco que se baseia em valores p e significância estatística para definir uma descoberta verdadeira. Em vez de procurar apenas respostas sim ou não, estamos começando a considerar a magnitude estimada da variação sexual em uma espécie, o grau de incerteza nessa estimativa e como essas medidas se comparam a outras espécies. Essa abordagem oferece uma análise mais sutil para questões desafiadoras na paleontologia, bem como em muitos outros campos da ciência.

Diferenças entre homens e mulheres O dimorfismo sexual é quando machos e fêmeas de uma determinada espécie diferem em média em uma característica particular – não incluindo sua anatomia reprodutiva. Exemplos clássicos são como os cervos machos têm chifres e os pavões machos têm penas de cauda chamativas, enquanto as fêmeas não têm essas características.

O dimorfismo também pode ser sutil e pouco chamativo. Muitas vezes a diferença é de grau, como diferenças no tamanho médio do corpo entre machos e fêmeas – como nos gorilas. Nesses casos modestos, os pesquisadores usam estatísticas para determinar se uma característica difere em média entre homens e mulheres.

Em muitas espécies, como esses patos mandarim, machos (esquerda) e fêmeas (direita) parecem muito diferentes. Crédito:Francis C. Franklin via WikimediaCommons, CC BY-SA

O dilema dos dinossauros Estudar o dimorfismo sexual em animais extintos é repleto de incertezas. Se você e eu desenterrarmos fósseis semelhantes da mesma espécie, eles inevitavelmente serão ligeiramente diferentes. Essas diferenças podem ser devidas ao sexo, mas também podem ser causadas pela idade – pássaros jovens são felpudos, pássaros adultos são elegantes. Eles também podem ser devidos à genética não relacionada ao sexo, como a cor dos olhos em humanos.

Se os paleontólogos tivessem milhares de fósseis para estudar de todas as espécies, as muitas fontes de variação biológica não teriam tanta importância. Unfortunately, the ravages of time have left the fossil record painfully incomplete, often with less than a dozen good specimens for large, extinct vertebrate species. Additionally, there is currently no way to identify the sex of an individual fossil except in rare cases where obvious clues exist, like eggs preserved within the body cavity.

So where does all this leave the debate on whether male and female dinosaurs had differences within traits? On the one hand, birds—which are direct descendants of dinosaurs—commonly show sexual dimorphism. So do crocodilians, dinosaurs' next closest living relatives. Evolutionary theory also predicts that, since dinosaurs reproduced with sperm and egg, there would be a benefit to sexual dimorphism.

These things all suggest that dinosaurs likely were sexually dimorphic. But in science you need to be quantitative. The challenge is that there is little in the way of statistically significant analyses of the fossil record to support dimorphism.

It’s possible that variation among individual dinosaurs of the same species could be due to sexual dimorphism, but there are rarely good enough samples to assert so using traditional statistics. Credit:James Ormiston, CC BY-ND

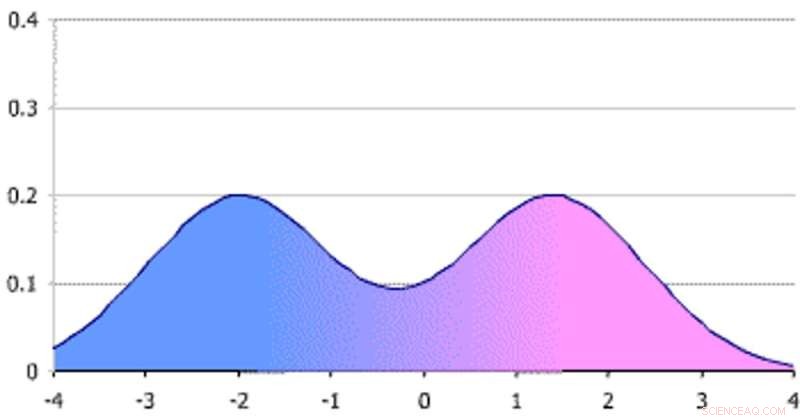

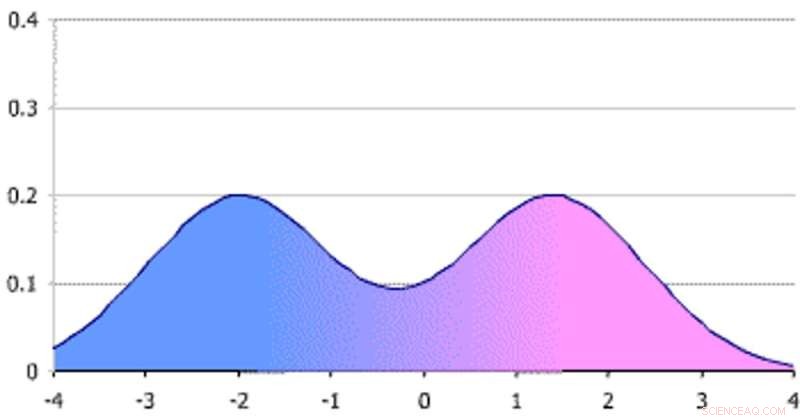

Statistical shifts There are a couple of ways paleontologists could test for sexual dimorphism. They could look to see if there are statistically significant differences between fossils from presumed males and females, but there are very few specimens where researchers know the sex. Another method is to see whether there are two distinct groupings of a trait, called a bimodal distribution, which could suggest a difference between males and females.

To tell whether a perceived difference between two groups is true, scientists have traditionally used a tool called the p-value. P-values quantify the probability of a result being due to random chance. If a p-value is low enough, the result is deemed "statistically significant" and considered unlikely to have happened by chance.

But p-values can be heavily influenced by sample size and the design of the study, in addition to the actual degree of sexual dimorphism. Because of the very small sample size of fossils, relying on this statistical technique makes it exceedingly difficult to categorically proclaim what dinosaur species were dimorphic.

The weakness of the black-or-white approach that focuses solely on whether a result is statistically significant has led to hundreds of scientists calling to abandon significance testing with p-values in favor of something called effect size statistics. Using this approach, researchers would simply report the measured difference between two groups and the uncertainty in that measurement.

Very large sex differences can create a bimodal distribution that looks like two distinct groupings of a certain measurement. Credit:Maksim via WikimediaCommons, CC BY

Effect size statistics I have begun to apply effect size statistics in my research on dinosaurs. My colleagues and I compared sexual dimorphism in body size between three different dinosaurs:the duck-billed Maiasaura, Tyrannosaurus rex and Psittacosaurus, a small relative of Triceratops. None of these species would be expected to show statistically significant size differences between males and females according to p-values. But that approach does not capture the nature of the variation within these species.

When we instead used effect size statistics, we were able to estimate that male and female Maiasaura demonstrate a greater difference in body mass compared to the other two species and that we had a higher confidence in this estimate as well. A few of the characteristics within the data helped reduce the uncertainty. First, we had a large number of Maiasaura fossils, from individuals of various ages. These bones very nicely fit with trajectories of how size changes as an individual grows from juvenile to adult, so we could control for differences due to age and instead focus on differences due to sex.

Additionally, the Maiasaura fossils all come from a single bone bed of individuals that died in the same place at the same time. This means that variation between individuals is likely not due to them being different species from different regions or time periods.

If my colleagues and I had approached the problem expecting a yes or no answer on whether males and females differed in size, we would have completely missed all of these intricacies. Effect size statistics allow researchers to produce much more nuanced and, I think, informative results. It is almost as much a difference in the philosophical approach to science as it is a mathematical one.

Using effect size statistics, researchers were able to determine that the duck-billed dinosaur Maiasaura showed a larger amount of dimorphism with the least uncertainty in that estimate compared to other dinosaurs. Credit:Daderot via WikimediaCommons

Studying dinosaur dimorphism is not the only place p-values create issues. Many fields of science, including medicine and psychology, are having similar debates about issues in statistics and a worrying problem of unrepeatable studies.

Embracing uncertainty in data—rather than looking for black-or-white answers to questions like whether male and female dinosaurs were sexually dimorphic—can help elucidate dinosaur biology. But this shift in thinking may be felt far and wide across the sciences. A careful consideration of problems within statistics could have deep impacts across many fields.