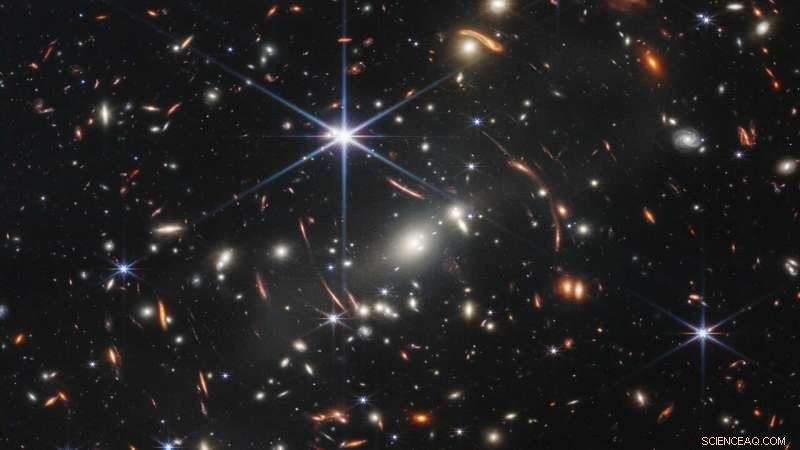

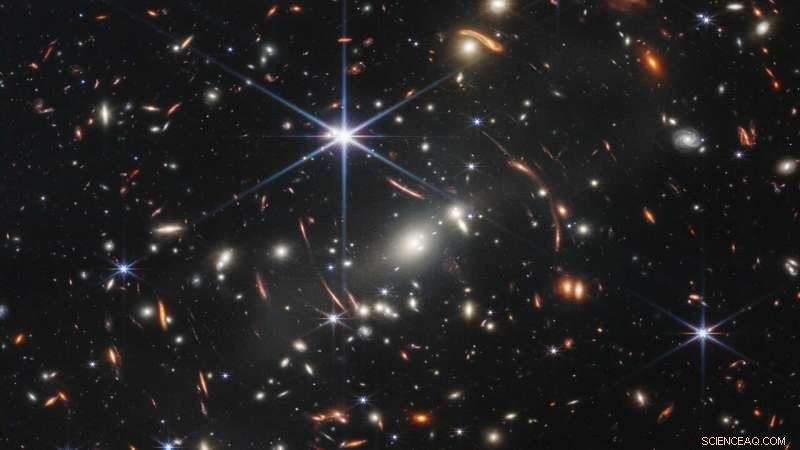

Esta imagem – a primeira divulgada pelo Telescópio Espacial James Webb da NASA – mostra o aglomerado de galáxias SMACS 0723. Algumas das galáxias aparecem manchadas ou esticadas devido a um fenômeno chamado lente gravitacional. Esse efeito pode ajudar os cientistas a mapear a presença de matéria escura no universo. Crédito:NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

Poderia um dos maiores quebra-cabeças da astrofísica ser resolvido reformulando a teoria da gravidade de Albert Einstein? Um novo estudo de co-autoria de cientistas da NASA diz que ainda não.

O universo está se expandindo em ritmo acelerado, e os cientistas não sabem por quê. Esse fenômeno parece contradizer tudo o que os pesquisadores entendem sobre o efeito da gravidade no cosmos:é como se você jogasse uma maçã no ar e ela continuasse subindo, cada vez mais rápido. A causa da aceleração, apelidada de energia escura, permanece um mistério.

Um novo estudo do Dark Energy Survey internacional, usando o Telescópio de 4 metros Victor M. Blanco no Chile, marca o mais recente esforço para determinar se tudo isso é simplesmente um mal-entendido:que as expectativas de como a gravidade funciona na escala de todo o universo são falhos ou incompletos. Esse mal-entendido em potencial pode ajudar os cientistas a explicar a energia escura. Mas o estudo – um dos testes mais precisos já feitos da teoria da gravidade de Albert Einstein em escalas cósmicas – descobre que o entendimento atual ainda parece estar correto.

Os resultados, de autoria de um grupo de cientistas que inclui alguns do Laboratório de Propulsão a Jato da NASA, foram apresentados quarta-feira, 23 de agosto, na Conferência Internacional de Física de Partículas e Cosmologia (COSMO'22), no Rio de Janeiro. O trabalho ajuda a preparar o terreno para dois próximos telescópios espaciais que investigarão nossa compreensão da gravidade com precisão ainda maior do que o novo estudo e talvez finalmente resolvam o mistério.

Mais de um século atrás, Albert Einstein desenvolveu sua Teoria da Relatividade Geral para descrever a gravidade e, até agora, previu com precisão tudo, desde a órbita de Mercúrio até a existência de buracos negros. Mas se essa teoria não pode explicar a energia escura, alguns cientistas argumentam, então talvez eles precisem modificar algumas de suas equações ou adicionar novos componentes.

Para descobrir se esse é o caso, os membros do Dark Energy Survey procuraram evidências de que a força da gravidade variou ao longo da história do universo ou em distâncias cósmicas. Uma descoberta positiva indicaria que a teoria de Einstein está incompleta, o que pode ajudar a explicar a expansão acelerada do universo. Eles também examinaram dados de outros telescópios além do Blanco, incluindo o satélite Planck da ESA (Agência Espacial Européia), e chegaram à mesma conclusão.

Este vídeo explica o fenômeno chamado lente gravitacional, que pode fazer com que imagens de galáxias pareçam distorcidas ou manchadas. This distortion is caused by gravity, and scientists can use the effect to detect dark matter, which does not emit or reflect light. Credit:NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center The study finds Einstein's theory still works. So no explanation for dark energy yet. But this research will feed into two upcoming missions:ESA's Euclid mission, slated for launch no earlier than 2023, which has contributions from NASA; and NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, targeted for launch no later than May 2027. Both telescopes will search for changes in the strength of gravity over time or distance.

Blurred Vision How do scientists know what happened in the universe's past? By looking at distant objects. A light-year is a measure of the distance light can travel in a year (about 6 trillion miles, or about 9.5 trillion kilometers). That means an object one light-year away appears to us as it was one year ago, when the light first left the object. And galaxies billions of light-years away appear to us as they did billions of years ago. The new study looked at galaxies stretching back about 5 billion years in the past. Euclid will peer 8 billion years into the past, and Roman will look back 11 billion years.

The galaxies themselves don't reveal the strength of gravity, but how they look when viewed from Earth does. Most matter in our universe is dark matter, which does not emit, reflect, or otherwise interact with light. While scientists don't know what it's made of, they know it's there, because its gravity gives it away:Large reservoirs of dark matter in our universe warp space itself. As light travels through space, it encounters these portions of warped space, causing images of distant galaxies to appear curved or smeared. This was on display in one of first images released from NASA's James Webb Space Telescope.

Dark Energy Survey scientists search galaxy images for more subtle distortions due to dark matter bending space, an effect called weak gravitational lensing. The strength of gravity determines the size and distribution of dark matter structures, and the size and distribution in turn determine how warped those galaxies appear to us. That's how images can reveal the strength of gravity at different distances from Earth and distant times throughout the universe's history. The group has now measured the shapes of over 100 million galaxies, and so far, the observations match what's predicted by Einstein's theory.

"There is still room to challenge Einstein's theory of gravity, as measurements gets more and more precise," said study co-author Agnès Ferté, who conducted the research as a postdoctoral researcher at JPL. "But we still have so much to do before we're ready for Euclid and Roman. So it's essential we continue to collaborate with scientists around the world on this problem as we've done with the Dark Energy Survey."

+ Explorar mais NASA's Roman mission will test competing cosmic acceleration theories