Os alquimistas antigos tentaram transformar o chumbo e outros metais comuns em ouro e platina. Químicos modernos no laboratório de Paul Chirik em Princeton estão transformando reações que dependeram de metais preciosos que não agridem o meio ambiente, encontrar alternativas mais baratas e ecológicas para substituir a platina, ródio e outros metais preciosos na produção de drogas e outras reações.

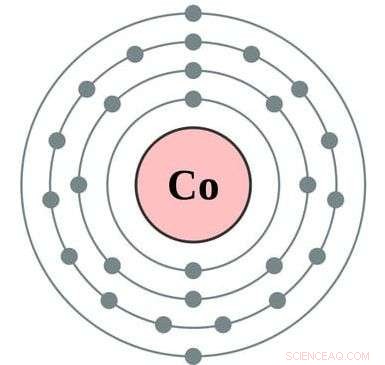

Eles descobriram uma abordagem revolucionária que usa cobalto e metanol para produzir uma droga para epilepsia que anteriormente exigia ródio e diclorometano, um solvente tóxico. A nova reação deles funciona mais rápido e mais barato, e provavelmente tem um impacto ambiental muito menor, disse Chirik, o professor de química Edwards S. Sanford. "Isso destaca um princípio importante na química verde - que a solução mais ambiental também pode ser a preferida quimicamente, "disse ele. A pesquisa foi publicada na revista Ciência em 25 de maio.

"A descoberta e o processo farmacêutico envolvem todos os tipos de elementos exóticos, "Chirik disse." Começamos este programa há talvez 10 anos, e foi realmente motivado pelo custo. Metais como ródio e platina são muito caros, mas conforme o trabalho evoluiu, percebemos que isso é muito mais do que simplesmente definir preços. ... Existem enormes preocupações ambientais, se você pensar em desenterrar platina do solo. Tipicamente, você tem que ir cerca de uma milha de profundidade e mover 10 toneladas de terra. Isso tem uma pegada enorme de dióxido de carbono. "

Chirik e sua equipe de pesquisa fizeram parceria com químicos da Merck &Co., Inc., para encontrar maneiras mais ecológicas de criar os materiais necessários para a química moderna de medicamentos. A colaboração foi possibilitada pelo programa Oportunidades de Concessão de Oportunidades para Ligação Acadêmica com a Indústria (GOALI) da National Science Foundation.

Um aspecto complicado é que muitas moléculas têm formas destras e canhotas que reagem de forma diferente, com conseqüências às vezes perigosas. A Food and Drug Administration tem requisitos rígidos para garantir que os medicamentos tenham apenas uma "mão" de cada vez, conhecidas como drogas de enantiômero único.

"Os químicos são desafiados a descobrir métodos para sintetizar apenas uma mão de moléculas de drogas, em vez de sintetizar ambas e depois separar, "disse Chirik." Catalisadores de metal, historicamente baseado em metais preciosos como o ródio, foram incumbidos de resolver este desafio. Nosso artigo demonstra que um metal mais abundante na Terra, cobalto, pode ser usado para sintetizar o medicamento para epilepsia Keppra como apenas uma mão. "

Cinco anos atrás, pesquisadores no laboratório de Chirik demonstraram que o cobalto pode fazer moléculas orgânicas de enantiômero único, mas apenas usando compostos relativamente simples e não medicamente ativos - e usando solventes tóxicos.

"Fomos inspirados a levar nossa demonstração de princípio a exemplos do mundo real e demonstrar que o cobalto pode superar os metais preciosos e trabalhar em condições mais compatíveis com o meio ambiente, ", disse ele. Eles descobriram que sua nova técnica à base de cobalto é mais rápida e mais seletiva do que a abordagem patenteada de ródio.

"Nosso artigo demonstra um caso raro em que um metal de transição abundante na Terra pode superar o desempenho de um metal precioso na síntese de drogas de enantiômero único, "ele disse." Estamos começando a fazer a transição para que os catalisadores abundantes na Terra não substituam apenas os de metais preciosos, mas eles oferecem vantagens distintas, seja uma nova química que ninguém nunca viu antes ou uma reatividade aprimorada ou pegada ambiental reduzida. "

Os metais básicos não são apenas mais baratos e muito mais ecologicamente corretos do que os metais raros, mas a nova técnica opera em metanol, which is much greener than the chlorinated solvents that rhodium requires.

"The manufacture of drug molecules, because of their complexity, is one of the most wasteful processes in the chemical industry, " said Chirik. "The majority of the waste generated is from the solvent used to conduct the reaction. The patented route to the drug relies on dichloromethane, one of the least environmentally friendly organic solvents. Our work demonstrates that Earth-abundant catalysts not only operate in methanol, a green solvent, but also perform optimally in this medium.

"This is a transformative breakthrough for Earth-abundant metal catalysts, as these historically have not been as robust as precious metals. Our work demonstrates that both the metal and the solvent medium can be more environmentally compatible."

Methanol is a common solvent for one-handed chemistry using precious metals, but this is the first time it has been shown to be useful in a cobalt system, noted Max Friedfeld, the first author on the paper and a former graduate student in Chirik's lab.

Cobalt's affinity for green solvents came as a surprise, said Chirik. "For a decade, catalysts based on Earth-abundant metals like iron and cobalt required very dry and pure conditions, meaning the catalysts themselves were very fragile. By operating in methanol, not only is the environmental profile of the reaction improved, but the catalysts are much easier to use and handle. This means that cobalt should be able to compete or even outperform precious metals in many applications that extend beyond hydrogenation."

The collaboration with Merck was key to making these discoveries, noted the researchers.

Chirik said:"This is a great example of an academic-industrial collaboration and highlights how the very fundamental—how do electrons flow differently in cobalt versus rhodium?—can inform the applied—how to make an important medicine in a more sustainable way. I think it is safe to say that we would not have discovered this breakthrough had the two groups at Merck and Princeton acted on their own."

The key was volume, said Michael Shevlin, an associate principal scientist at the Catalysis Laboratory in the Department of Process Research &Development at Merck &Co., Inc., and a co-author on the paper.

"Instead of trying just a few experiments to test a hypothesis, we can quickly set up large arrays of experiments that cover orders of magnitude more chemical space, " Shevlin said. "The synergy is tremendous; scientists like Max Friedfeld and [co-author and graduate student] Aaron Zhong can conduct hundreds of experiments in our lab, and then take the most interesting results back to Princeton to study in detail. What they learn there then informs the next round of experimentation here."

Chirik's lab focuses on "homogenous catalysis, " the term for reactions using materials that have been dissolved in industrial solvents.

"Homogenous catalysis is usually the realm of these precious metals, the ones at the bottom of the periodic table, " Chirik said. "Because of their position on the periodic table, they tend to go by very predictable electron changes—two at a time—and that's why you can make jewelry out of these elements, because they don't oxidize, they don't interact with oxygen. So when you go to the Earth-abundant elements, usually the ones on the first row of the periodic table, the electronic structure—how the electrons move in the element—changes, and so you start getting one-electron chemistry, and that's why you see things like rust for these elements.

Chirik's approach proposes a radical shift for the whole field, said Vy Dong, a chemistry professor at the University of California-Irvine who was not involved in the research. "Traditional chemistry happens through what they call two-electron oxidations, and Paul's happens through one-electron oxidation, " she said. "That doesn't sound like a big difference, but that's a dramatic difference for a chemist. That's what we care about—how things work at the level of electrons and atoms. When you're talking about a pathway that happens via half of the electrons that you'd normally expect, it's a big deal. ... That's why this work is really exciting. You can imagine, once we break free from that mold, you can start to apply it to other things, também."

"We're working in an area of the periodic table where people haven't, por muito tempo, so there's a huge wealth of new fundamental chemistry, " said Chirik. "By learning how to control this electron flow, the world is open to us."