Altruísmo em pássaros? As pegas enganaram os cientistas ajudando uns aos outros a remover dispositivos de rastreamento

Crédito:Shutterstock

Quando anexamos minúsculos dispositivos de rastreamento semelhantes a mochilas a cinco pegas australianas para um estudo piloto, não esperávamos descobrir um comportamento social totalmente novo raramente visto em pássaros.

Nosso objetivo era aprender mais sobre o movimento e a dinâmica social dessas aves altamente inteligentes e testar esses dispositivos novos, duráveis e reutilizáveis. Em vez disso, os pássaros nos enganaram.

Como explica nosso novo trabalho de pesquisa, as pegas começaram a mostrar evidências de comportamento cooperativo de "resgate" para ajudar umas às outras a remover o rastreador.

Embora estejamos familiarizados com o fato de as pegas serem criaturas inteligentes e sociais, esta foi a primeira vez que conhecemos que mostrou esse tipo de comportamento aparentemente altruísta:ajudar outro membro do grupo sem obter uma recompensa imediata e tangível.

Testando novos dispositivos empolgantes Como cientistas acadêmicos, estamos acostumados a experimentos que dão errado de uma forma ou de outra. Substâncias expiradas, equipamentos com defeito, amostras contaminadas, falta de energia não planejada – tudo isso pode atrasar meses (ou até anos) de pesquisas cuidadosamente planejadas.

Para aqueles de nós que estudam animais, e especialmente comportamento, a imprevisibilidade faz parte da descrição do trabalho. Esta é a razão pela qual muitas vezes exigimos estudos-piloto.

Um dos rastreadores que anexamos a cinco pegas, que pesa menos de um grama. Crédito:Dominique Potvin, Autor fornecido

Nosso estudo piloto foi um dos primeiros desse tipo – a maioria dos rastreadores é grande demais para caber em pássaros médios a pequenos, e aqueles que o fazem tendem a ter capacidade muito limitada de armazenamento de dados ou vida útil da bateria. Eles também tendem a ser de uso único.

Um aspecto novo de nossa pesquisa foi o design do arnês que segurava o rastreador. Criamos um método que não exigia que os pássaros fossem capturados novamente para baixar dados preciosos ou reutilizar os pequenos dispositivos.

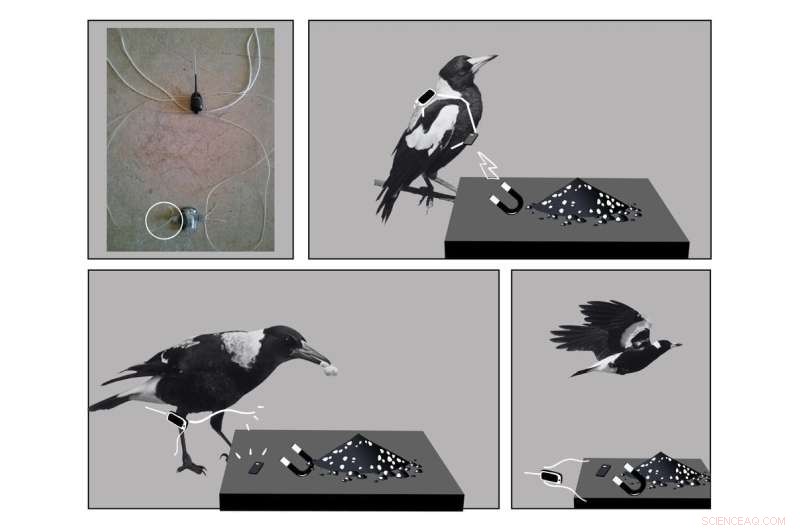

Treinamos um grupo de pegas locais para chegar a uma "estação" externa de alimentação terrestre que poderia carregar sem fio a bateria do rastreador, baixar dados ou liberar o rastreador e o chicote usando um ímã.

O arnês era resistente, com apenas um ponto fraco onde o ímã poderia funcionar. Para remover o arnês, era necessário aquele ímã ou uma tesoura muito boa. Ficamos entusiasmados com o design, pois abriu muitas possibilidades de eficiência e permitiu que muitos dados fossem coletados.

Queríamos ver se o novo design funcionaria conforme o planejado e descobrir que tipo de dados poderíamos coletar. Até onde as pegas foram? Eles tinham padrões ou horários ao longo do dia em termos de movimento e socialização? Como a idade, sexo ou posição dominante afetaram suas atividades?

All this could be uncovered using the tiny trackers—weighing less than one gram—we successfully fitted five of the magpies with. All we had to do was wait, and watch, and then lure the birds back to the station to gather the valuable data.

Magpies playing together. It was not to be Many animals that live in societies cooperate with one another to ensure the health, safety and survival of the group. In fact, cognitive ability and social cooperation has been found to correlate. Animals living in larger groups tend to have an increased capacity for problem solving, such as hyenas, spotted wrasse, and house sparrows.

Australian magpies are no exception. As a generalist species that excels in problem solving, it has adapted well to the extreme changes to their habitat from humans.

Australian magpies generally live in social groups of between two and 12 individuals, cooperatively occupying and defending their territory through song choruses and aggressive behaviors (such as swooping). These birds also breed cooperatively, with older siblings helping to raise young.

During our pilot study, we found out how quickly magpies team up to solve a group problem. Within ten minutes of fitting the final tracker, we witnessed an adult female without a tracker working with her bill to try and remove the harness off of a younger bird.

Within hours, most of the other trackers had been removed. By day 3, even the dominant male of the group had its tracker successfully dismantled.

We don't know if it was the same individual helping each other or if they shared duties, but we had never read about any other bird cooperating in this way to remove tracking devices.

Our new tracker design was innovative, allowing a magnet to release the harness. Credit:Dominique Potvin, Author provided

The birds needed to problem solve, possibly testing at pulling and snipping at different sections of the harness with their bill. They also needed to willingly help other individuals, and accept help.

The only other similar example of this type of behavior we could find in the literature was that of Seychelles warblers helping release others in their social group from sticky Pisonia seed clusters. This is a very rare behavior termed "rescuing."

Saving magpies So far, most bird species that have been tracked haven't necessarily been very social or considered to be cognitive problem solvers, such as waterfowl and raptors. We never considered the magpies may perceive the tracker as some kind of parasite that requires removal.

Tracking magpies is crucial for conservation efforts, as these birds are vulnerable to the increasing frequency and intensity of heatwaves under climate change.

In a study published this week, Perth researchers showed the survival rate of magpie chicks in heatwaves can be as low as 10%.

Importantly, they also found that higher temperatures resulted in lower cognitive performance for tasks such as foraging. This might mean cooperative behaviors become even more important in a continuously warming climate.

Just like magpies, we scientists are always learning to problem solve. Now we need to go back to the drawing board to find ways of collecting more vital behavioral data to help magpies survive in a changing world.