Uma floresta tropical na América do Sul. Crédito:Shutterstock / BorneoRimbawan

Uma manhã em 2009, Eu sentei em um ônibus barulhento subindo uma montanha no centro da Costa Rica, tonto de fumaça de diesel enquanto eu agarrava minhas muitas malas. Eles continham milhares de tubos de ensaio e frascos de amostra, uma escova de dentes, um caderno à prova d'água e duas mudas de roupa.

Eu estava a caminho da Estação Biológica La Selva, onde eu passaria vários meses estudando o molhado, a resposta da floresta de várzea às secas cada vez mais comuns. Em ambos os lados da estrada estreita, as árvores se misturaram com a névoa como aquarelas transformando-se em papel, dando a impressão de uma floresta primitiva infinita banhada por nuvens.

Enquanto eu olhava pela janela para o cenário imponente, Eu me perguntei como eu poderia esperar entender uma paisagem tão complexa. Eu sabia que milhares de pesquisadores em todo o mundo estavam lutando com as mesmas questões, tentando entender o destino das florestas tropicais em um mundo em rápida mudança.

Nossa sociedade exige muito desses frágeis ecossistemas, que controlam a disponibilidade de água doce para milhões de pessoas e abrigam dois terços da biodiversidade terrestre do planeta. E cada vez mais, colocamos uma nova demanda nessas florestas - para nos salvar da mudança climática causada pelo homem.

As plantas absorvem CO 2 da atmosfera, transformando-o em folhas, madeira e raízes. Este milagre cotidiano gerou esperanças de que as plantas - especialmente as árvores tropicais de crescimento rápido - possam atuar como um freio natural na mudança climática, capturando muito do CO 2 emitido pela queima de combustível fóssil. Através do mundo, governos, empresas e instituições de caridade de conservação se comprometeram a conservar ou plantar um grande número de árvores.

Mas o fato é que não existem árvores suficientes para compensar as emissões de carbono da sociedade - e nunca haverá. Recentemente, conduzi uma revisão da literatura científica disponível para avaliar quanto carbono as florestas poderiam absorver de maneira viável. Se maximizássemos absolutamente a quantidade de vegetação que toda a terra na Terra poderia conter, sequestraríamos carbono suficiente para compensar cerca de dez anos de emissões de gases de efeito estufa nas taxas atuais. Depois disso, não poderia haver mais aumento na captura de carbono.

No entanto, o destino de nossa espécie está intimamente ligado à sobrevivência das florestas e à biodiversidade que elas contêm. Correndo para plantar milhões de árvores para captura de carbono, poderíamos estar inadvertidamente danificando as próprias propriedades florestais que as tornam tão vitais para o nosso bem-estar? Para responder a esta pergunta, precisamos considerar não apenas como as plantas absorvem CO 2 , mas também como eles fornecem as bases verdes robustas para os ecossistemas terrestres.

Como as plantas lutam contra as mudanças climáticas

Plantas convertem CO 2 gás em açúcares simples em um processo conhecido como fotossíntese. Esses açúcares são então usados para construir os corpos vivos das plantas. Se o carbono capturado acabar na madeira, ele pode ser trancado longe da atmosfera por muitas décadas. Conforme as plantas morrem, seus tecidos se deterioram e são incorporados ao solo.

Bonnie Waring conduzindo pesquisas na Estação Biológica La Selva, Costa Rica, 2011. Autor fornecido

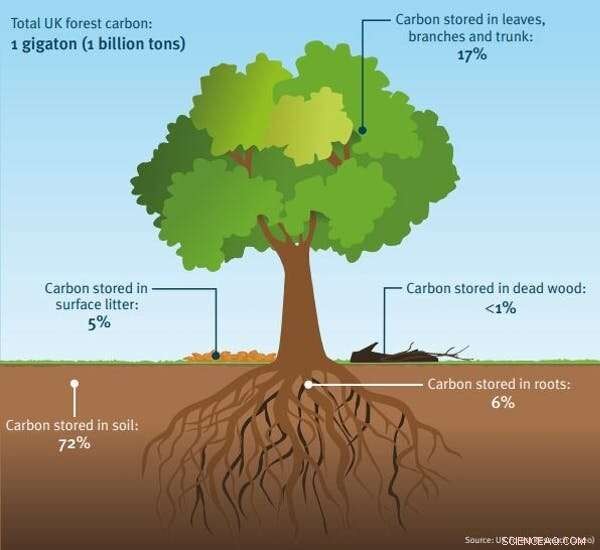

Embora este processo libere naturalmente CO 2 através da respiração (ou respiração) de micróbios que decompõem organismos mortos, alguma fração do carbono vegetal pode permanecer no subsolo por décadas ou mesmo séculos. Juntos, as plantas terrestres e os solos detêm cerca de 2, 500 gigatoneladas de carbono - cerca de três vezes mais do que é mantido na atmosfera.

Como as plantas (especialmente as árvores) são excelentes depósitos naturais de carbono, faz sentido que o aumento da abundância de plantas em todo o mundo possa reduzir o CO atmosférico 2 concentrações.

As plantas precisam de quatro ingredientes básicos para crescer:luz, CO 2 , água e nutrientes (como nitrogênio e fósforo, os mesmos elementos presentes no fertilizante vegetal). Milhares de cientistas em todo o mundo estudam como o crescimento das plantas varia em relação a esses quatro ingredientes, para prever como a vegetação responderá às mudanças climáticas.

Esta é uma tarefa surpreendentemente desafiadora, dado que os humanos estão modificando simultaneamente muitos aspectos do ambiente natural aquecendo o globo, alterando os padrões de chuva, dividir grandes extensões de floresta em pequenos fragmentos e introduzir espécies exóticas onde não pertencem. Existem também mais de 350, 000 espécies de plantas com flores em terra e cada uma responde aos desafios ambientais de uma forma única.

Devido às formas complicadas pelas quais os humanos estão alterando o planeta, Há muito debate científico sobre a quantidade precisa de carbono que as plantas podem absorver da atmosfera. Mas os pesquisadores estão de acordo unânime de que os ecossistemas terrestres têm uma capacidade finita de absorver carbono.

Se garantirmos que as árvores tenham água suficiente para beber, as florestas crescerão altas e exuberantes, criando copas sombreadas que deixam as árvores menores sem luz. Se aumentarmos a concentração de CO 2 no ar, as plantas o absorvem avidamente - até que não consigam mais extrair fertilizante suficiente do solo para atender às suas necessidades. Assim como um padeiro fazendo um bolo, plantas requerem CO 2 , nitrogênio e fósforo em proporções particulares, seguindo uma receita específica para a vida.

Em reconhecimento a essas restrições fundamentais, os cientistas estimam que os ecossistemas terrestres podem conter vegetação adicional suficiente para absorver entre 40 e 100 gigatoneladas de carbono da atmosfera. Uma vez que esse crescimento adicional seja alcançado (um processo que levará várias décadas), não há capacidade de armazenamento adicional de carbono na terra.

Mas nossa sociedade está atualmente despejando CO 2 para a atmosfera a uma taxa de dez gigatoneladas de carbono por ano. Os processos naturais terão dificuldade em acompanhar o dilúvio de gases de efeito estufa gerado pela economia global. Por exemplo, Calculei que um único passageiro em um vôo de ida e volta de Melbourne a Nova York emitirá aproximadamente o dobro de carbono (1.600 kg C) do que o contido em um carvalho de meio metro de diâmetro (750 kg C).

Folha ao microscópio:pode-se observar o estoma que regula o oxigênio e o dióxido de carbono. Crédito:Shutterstock / Barbol

Perigo e promessa

Apesar de todas essas restrições físicas reconhecidas no crescimento das plantas, há uma proliferação de esforços em grande escala para aumentar a cobertura vegetal para mitigar a emergência climática - uma solução climática chamada "baseada na natureza". A grande maioria desses esforços se concentra na proteção ou expansão das florestas, já que as árvores contêm muitas vezes mais biomassa do que arbustos ou gramíneas e, portanto, representam maior potencial de captura de carbono.

No entanto, mal-entendidos fundamentais sobre a captura de carbono pelos ecossistemas terrestres podem ter consequências devastadoras, resultando em perdas de biodiversidade e um aumento de CO 2 concentrações. Isso parece um paradoxo - como o plantio de árvores pode impactar negativamente o meio ambiente?

A resposta está nas sutis complexidades da captura de carbono em ecossistemas naturais. Para evitar danos ambientais, devemos nos abster de estabelecer florestas onde elas naturalmente não pertencem, evitar "incentivos perversos" para cortar a floresta existente a fim de plantar novas árvores, e considere como as mudas plantadas hoje podem se sair nas próximas décadas.

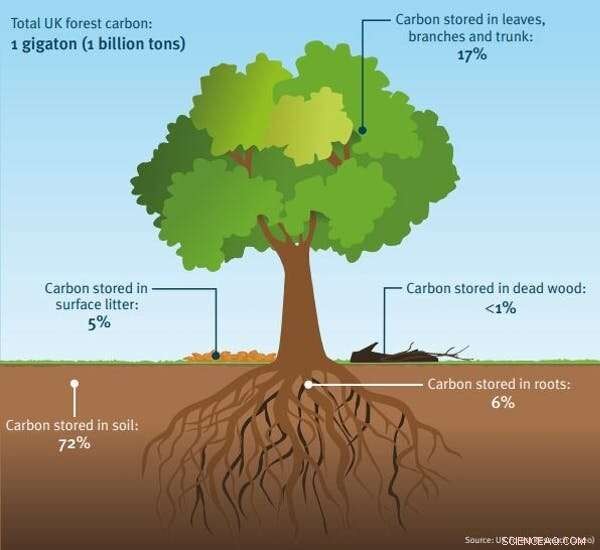

Antes de empreender qualquer expansão do habitat florestal, devemos garantir que as árvores sejam plantadas no lugar certo, porque nem todos os ecossistemas da terra podem ou devem suportar árvores. Plantar árvores em ecossistemas que normalmente são dominados por outros tipos de vegetação muitas vezes não resulta no sequestro de carbono a longo prazo.

Um exemplo particularmente ilustrativo vem das turfeiras escocesas - vastas áreas de terra onde a vegetação baixa (principalmente musgos e gramíneas) cresce constantemente encharcada, solo úmido. Como a decomposição é muito lenta nos solos ácidos e alagados, plantas mortas se acumulam por longos períodos de tempo, criando turfa. Não é apenas a vegetação que é preservada:as turfeiras também mumificam os chamados "corpos das turfeiras" - os restos quase intactos de homens e mulheres que morreram há milênios. Na verdade, As turfeiras do Reino Unido contêm 20 vezes mais carbono do que as encontradas nas florestas do país.

Mas no final do século 20, alguns pântanos escoceses foram drenados para o plantio de árvores. A secagem dos solos permitiu que mudas de árvores se estabelecessem, mas também fez com que a decomposição da turfa se acelerasse. A ecologista Nina Friggens e seus colegas da Universidade de Exeter estimaram que a decomposição da turfa em secagem liberou mais carbono do que as árvores em crescimento poderiam absorver. Claramente, as turfeiras podem proteger melhor o clima quando são deixadas por conta própria.

O mesmo é verdadeiro para pastagens e savanas, onde os incêndios são uma parte natural da paisagem e muitas vezes queimam árvores que são plantadas onde não pertencem. Este princípio também se aplica às tundras árticas, onde a vegetação nativa é coberta por neve durante todo o inverno, refletindo luz e calor de volta para o espaço. Plantando alto, árvores de folhas escuras nessas áreas podem aumentar a absorção de energia térmica, e levar ao aquecimento local.

Mas mesmo o plantio de árvores em habitats florestais pode levar a resultados ambientais negativos. Do ponto de vista do sequestro de carbono e da biodiversidade, todas as florestas não são iguais - as florestas estabelecidas naturalmente contêm mais espécies de plantas e animais do que as florestas plantadas. Eles costumam conter mais carbono, também. Mas as políticas destinadas a promover o plantio de árvores podem, sem querer, incentivar o desmatamento de habitats naturais bem estabelecidos.

Where carbon is stored in a typical temperate forest in the UK. Credit:UK Forest Research, CC BY

A recent high-profile example concerns the Mexican government's Sembrando Vida program, which provides direct payments to landowners for planting trees. O problema? Many rural landowners cut down well established older forest to plant seedlings. This decision, while quite sensible from an economic point of view, has resulted in the loss of tens of thousands of hectares of mature forest.

This example demonstrates the risks of a narrow focus on trees as carbon absorption machines. Many well meaning organizations seek to plant the trees which grow the fastest, as this theoretically means a higher rate of CO 2 "drawdown" from the atmosphere.

Yet from a climate perspective, what matters is not how quickly a tree can grow, but how much carbon it contains at maturity, and how long that carbon resides in the ecosystem. As a forest ages, it reaches what ecologists call a "steady state"—this is when the amount of carbon absorbed by the trees each year is perfectly balanced by the CO 2 released through the breathing of the plants themselves and the trillions of decomposer microbes underground.

This phenomenon has led to an erroneous perception that old forests are not useful for climate mitigation because they are no longer growing rapidly and sequestering additional CO 2 . The misguided "solution" to the issue is to prioritize tree planting ahead of the conservation of already established forests. This is analogous to draining a bathtub so that the tap can be turned on full blast:the flow of water from the tap is greater than it was before—but the total capacity of the bath hasn't changed. Mature forests are like bathtubs full of carbon. They are making an important contribution to the large, but finite, quantity of carbon that can be locked away on land, and there is little to be gained by disturbing them.

What about situations where fast growing forests are cut down every few decades and replanted, with the extracted wood used for other climate-fighting purposes? While harvested wood can be a very good carbon store if it ends up in long lived products (like houses or other buildings), surprisingly little timber is used in this way.

De forma similar, burning wood as a source of biofuel may have a positive climate impact if this reduces total consumption of fossil fuels. But forests managed as biofuel plantations provide little in the way of protection for biodiversity and some research questions the benefits of biofuels for the climate in the first place.

Fertilize a whole forest

Scientific estimates of carbon capture in land ecosystems depend on how those systems respond to the mounting challenges they will face in the coming decades. All forests on Earth—even the most pristine—are vulnerable to warming, changes in rainfall, increasingly severe wildfires and pollutants that drift through the Earth's atmospheric currents.

Some of these pollutants, Contudo, contain lots of nitrogen (plant fertilizer) which could potentially give the global forest a growth boost. By producing massive quantities of agricultural chemicals and burning fossil fuels, humans have massively increased the amount of "reactive" nitrogen available for plant use. Some of this nitrogen is dissolved in rainwater and reaches the forest floor, where it can stimulate tree growth in some areas.

Implications of large-scale tree planting in various climatic zones and ecosystems. Credit:Stacey McCormack/Köppen climate classification, Autor fornecido

As a young researcher fresh out of graduate school, I wondered whether a type of under-studied ecosystem, known as seasonally dry tropical forest, might be particularly responsive to this effect. There was only one way to find out:I would need to fertilize a whole forest.

Working with my postdoctoral adviser, the ecologist Jennifer Powers, and expert botanist Daniel Pérez Avilez, I outlined an area of the forest about as big as two football fields and divided it into 16 plots, which were randomly assigned to different fertilizer treatments. For the next three years (2015-2017) the plots became among the most intensively studied forest fragments on Earth. We measured the growth of each individual tree trunk with specialised, hand-built instruments called dendrometers.

We used baskets to catch the dead leaves that fell from the trees and installed mesh bags in the ground to track the growth of roots, which were painstakingly washed free of soil and weighed. The most challenging aspect of the experiment was the application of the fertilizers themselves, which took place three times a year. Wearing raincoats and goggles to protect our skin against the caustic chemicals, we hauled back-mounted sprayers into the dense forest, ensuring the chemicals were evenly applied to the forest floor while we sweated under our rubber coats.

Infelizmente, our gear didn't provide any protection against angry wasps, whose nests were often concealed in overhanging branches. Mas, our efforts were worth it. Depois de três anos, we could calculate all the leaves, wood and roots produced in each plot and assess carbon captured over the study period. We found that most trees in the forest didn't benefit from the fertilizers—instead, growth was strongly tied to the amount of rainfall in a given year.

This suggests that nitrogen pollution won't boost tree growth in these forests as long as droughts continue to intensify. To make the same prediction for other forest types (wetter or drier, younger or older, warmer or cooler) such studies will need to be repeated, adding to the library of knowledge developed through similar experiments over the decades. Yet researchers are in a race against time. Experiments like this are slow, painstaking, sometimes backbreaking work and humans are changing the face of the planet faster than the scientific community can respond.

Humans need healthy forests

Supporting natural ecosystems is an important tool in the arsenal of strategies we will need to combat climate change. But land ecosystems will never be able to absorb the quantity of carbon released by fossil fuel burning. Rather than be lulled into false complacency by tree planting schemes, we need to cut off emissions at their source and search for additional strategies to remove the carbon that has already accumulated in the atmosphere.

Does this mean that current campaigns to protect and expand forest are a poor idea? Emphatically not. The protection and expansion of natural habitat, particularly forests, is absolutely vital to ensure the health of our planet. Forests in temperate and tropical zones contain eight out of every ten species on land, yet they are under increasing threat. Nearly half of our planet's habitable land is devoted to agriculture, and forest clearing for cropland or pasture is continuing apace.

Enquanto isso, the atmospheric mayhem caused by climate change is intensifying wildfires, worsening droughts and systematically heating the planet, posing an escalating threat to forests and the wildlife they support. What does that mean for our species? Again and again, researchers have demonstrated strong links between biodiversity and so-called "ecosystem services"—the multitude of benefits the natural world provides to humanity.

Dendrometer devices wrapped around tree trunks to measure growth. Autor fornecido

Carbon capture is just one ecosystem service in an incalculably long list. Biodiverse ecosystems provide a dizzying array of pharmaceutically active compounds that inspire the creation of new drugs. They provide food security in ways both direct (think of the millions of people whose main source of protein is wild fish) and indirect (for example, a large fraction of crops are pollinated by wild animals).

Natural ecosystems and the millions of species that inhabit them still inspire technological developments that revolutionize human society. Por exemplo, take the polymerase chain reaction ("PCR") that allows crime labs to catch criminals and your local pharmacy to provide a COVID test. PCR is only possible because of a special protein synthesized by a humble bacteria that lives in hot springs.

As an ecologist, I worry that a simplistic perspective on the role of forests in climate mitigation will inadvertently lead to their decline. Many tree planting efforts focus on the number of saplings planted or their initial rate of growth—both of which are poor indicators of the forest's ultimate carbon storage capacity and even poorer metric of biodiversity. Mais importante, viewing natural ecosystems as "climate solutions" gives the misleading impression that forests can function like an infinitely absorbent mop to clean up the ever increasing flood of human caused CO 2 emissões.

Felizmente, many big organizations dedicated to forest expansion are incorporating ecosystem health and biodiversity into their metrics of success. A little over a year ago, I visited an enormous reforestation experiment on the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, operated by Plant-for-the-Planet—one of the world's largest tree planting organizations. After realizing the challenges inherent in large scale ecosystem restoration, Plant-for-the-Planet has initiated a series of experiments to understand how different interventions early in a forest's development might improve tree survival.

But that is not all. Led by Director of Science Leland Werden, researchers at the site will study how these same practices can jump-start the recovery of native biodiversity by providing the ideal environment for seeds to germinate and grow as the forest develops. These experiments will also help land managers decide when and where planting trees benefits the ecosystem and where forest regeneration can occur naturally.

Viewing forests as reservoirs for biodiversity, rather than simply storehouses of carbon, complicates decision making and may require shifts in policy. I am all too aware of these challenges. I have spent my entire adult life studying and thinking about the carbon cycle and I too sometimes can't see the forest for the trees. One morning several years ago, I was sitting on the rainforest floor in Costa Rica measuring CO 2 emissions from the soil—a relatively time intensive and solitary process.

As I waited for the measurement to finish, I spotted a strawberry poison dart frog—a tiny, jewel-bright animal the size of my thumb—hopping up the trunk of a nearby tree. Intrigado, I watched her progress towards a small pool of water held in the leaves of a spiky plant, in which a few tadpoles idly swam. Once the frog reached this miniature aquarium, the tiny tadpoles (her children, as it turned out) vibrated excitedly, while their mother deposited unfertilised eggs for them to eat. As I later learned, frogs of this species (Oophaga pumilio) take very diligent care of their offspring and the mother's long journey would be repeated every day until the tadpoles developed into frogs.

It occurred to me, as I packed up my equipment to return to the lab, that thousands of such small dramas were playing out around me in parallel. Forests are so much more than just carbon stores. They are the unknowably complex green webs that bind together the fates of millions of known species, with millions more still waiting to be discovered. To survive and thrive in a future of dramatic global change, we will have to respect that tangled web and our place in it.

Este artigo foi republicado de The Conversation sob uma licença Creative Commons. Leia o artigo original.