Um jogo online de montagem em prateleira, desenvolvido como prova de conceito. Crédito:Universidade do Sul da Califórnia

À medida que os robôs unem cada vez mais forças para trabalhar com humanos – de asilos a armazéns e fábricas – eles devem ser capazes de oferecer suporte proativamente. Mas primeiro, os robôs precisam aprender algo que sabemos instintivamente:como antecipar as necessidades das pessoas.

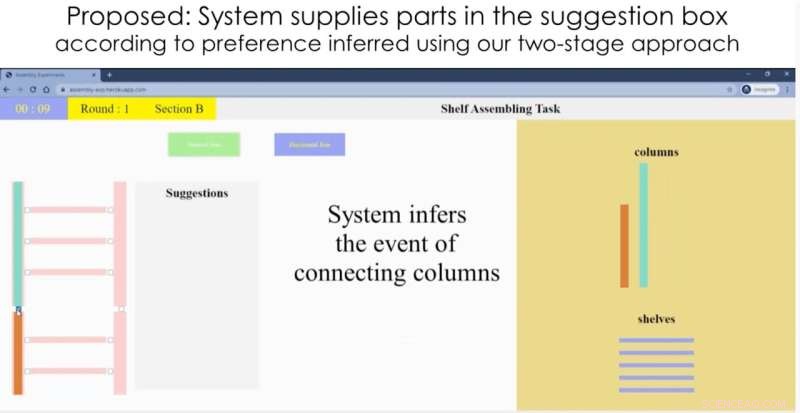

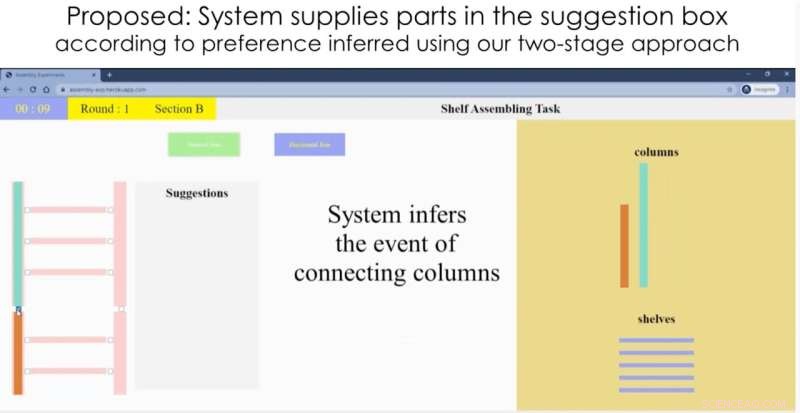

Com esse objetivo em mente, pesquisadores da USC Viterbi School of Engineering criaram um novo sistema robótico que prevê com precisão como um humano construirá uma estante IKEA e, em seguida, dá uma mão - fornecendo a prateleira, parafuso ou parafuso necessário para concluir a tarefa . A pesquisa foi apresentada na Conferência Internacional de Robótica e Automação em 30 de maio de 2021.

“Queremos que o humano e o robô trabalhem juntos – um robô pode ajudá-lo a fazer as coisas mais rápido e melhor, realizando tarefas de apoio, como buscar coisas”, disse o principal autor do estudo, Heramb Nemlekar. “Os humanos ainda realizarão as ações primárias, mas podem descarregar ações secundárias mais simples para o robô”.

Nemlekar, um Ph.D. estudante de ciência da computação, é supervisionado por Stefanos Nikolaidis, professor assistente de ciência da computação, e co-autor do artigo com Nikolaidis e SK Gupta, professor de aeroespacial, engenharia mecânica e ciência da computação que detém o Smith International Professorship in Mechanical Engineering.

Crédito:Universidade do Sul da Califórnia Adaptação a variações Em 2018, um robô criado por pesquisadores em Cingapura aprendeu a montar uma cadeira IKEA. Neste novo estudo, a equipe de pesquisa da USC pretende se concentrar na colaboração humano-robô.

Há vantagens em combinar a inteligência humana e a força do robô. Em uma fábrica, por exemplo, um operador humano pode controlar e monitorar a produção, enquanto o robô realiza o trabalho fisicamente extenuante. Os humanos também são mais hábeis nessas tarefas complicadas e delicadas, como mexer um parafuso para ajustá-lo.

O principal desafio a ser superado:os humanos tendem a realizar ações em diferentes ordens. Por exemplo, imagine que você está construindo uma estante de livros - você lida com as tarefas fáceis primeiro ou vai direto para as difíceis? Como o robô auxiliar se adapta rapidamente às variações de seus parceiros humanos?

“Os humanos podem dizer verbalmente ao robô o que eles precisam, mas isso não é eficiente”, disse Nikolaidis. "We want the robot to be able to infer what the human wants, based on some prior knowledge."

It turns out, robots can gather knowledge much like we do as humans:by "watching" people, and seeing how they behave. While we all tackle tasks in different ways, people tend to cluster around a handful of dominant preferences. If the robot can learn these preferences, it has a head start on predicting what you might do next.

A good collaborator Based on this knowledge, the team developed an algorithm that uses artificial intelligence to classify people into dominant "preference groups," or types, based on their actions. The robot was fed a kind of "manual" on humans:data gathered from an annotated video of 20 people assembling the bookcase. The researchers found people fell into four dominant preference groups.

In an IKEA furniture assembly task, a human stayed in a “work area” and performed the assembling actions, while the robot brought the required materials from storage area. Credit:University of Southern California

For instance, do you connect all the shelves to the frame on just one side first; or do you connect each shelf to the frame on both sides, before moving onto the next shelf? Depending on your preference category, the robot should bring you a new shelf, or a new set of screws. In a real-life IKEA furniture assembly task, a human stayed in a "work area" and assembled the bookcase, while the robot—a Kinova Gen 2 robot arm—learned the human's preferences, and brought the required materials from a storage area.

"The system very quickly associates a new user with a preference, with only a few actions," said Nemlekar.

"That's what we do as humans. If I want to work to work with you, I'm not going to start from zero. I'll watch what you do, and then infer from that what you might do next."

In this initial version, the researchers entered each action into the robotic system manually, but future iterations could learn by "watching" the human partner using computer vision. The team is also working on a new test-case:humans and robots working together to build—and then fly—a model airplane, a task requiring close attention to detail.

Refining the system is a step towards having "intuitive" helper robots in our daily lives, said Nikolaidis. Although the focus is currently on collaborative manufacturing, the same insights could be used to help people with disabilities, with applications including robot-assisted eating or meal prep.

"If we will soon have robots in our homes, in our work, in care facilities, it's important for robots to infer and adapt to people's preferences," said Nikolaidis. "The robot needs to be a teammate and a good collaborator. I think having some notion of user preference and being able to learn variability is what will make robots more accepted."