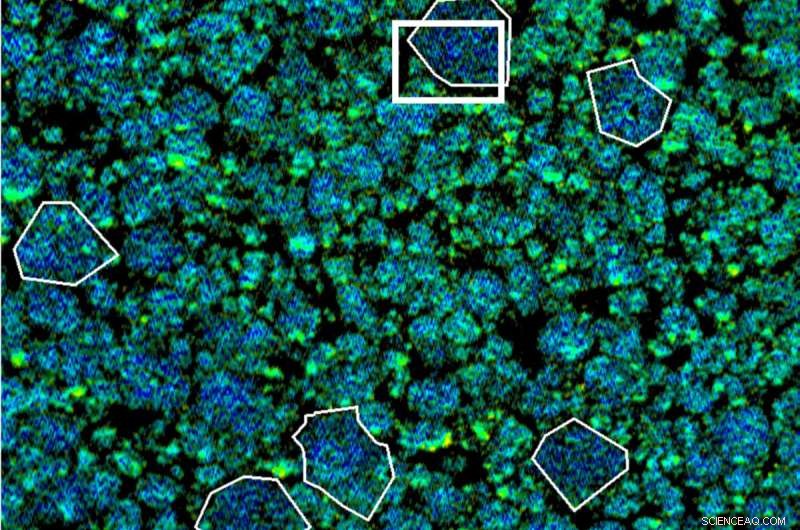

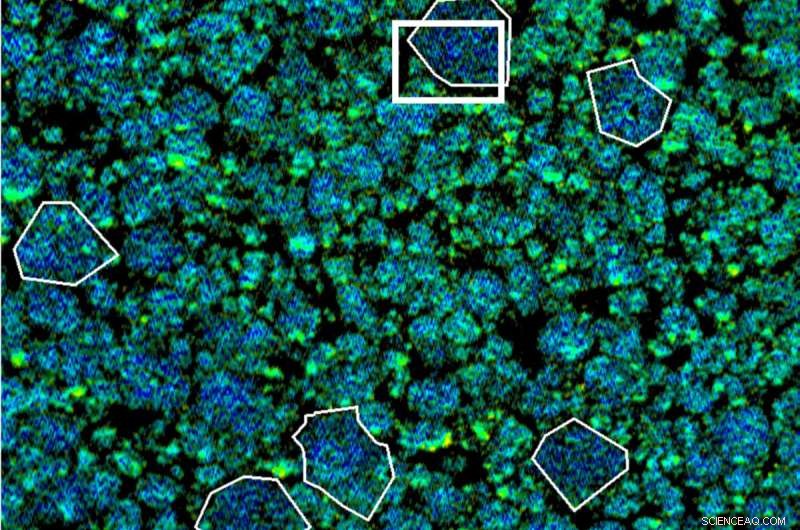

Medições detalhadas de raios-X na Fonte de Luz Avançada ajudaram uma equipe de pesquisa co-liderada pelo Berkeley Lab, SLAC e Universidade de Stanford a revelar como o oxigênio escoa dos bilhões de nanopartículas que compõem os eletrodos da bateria de íons de lítio. Crédito:Berkeley Lab

Durante um período de três meses, o carro médio nos EUA produz uma tonelada métrica de dióxido de carbono. Multiplique isso por todos os carros movidos a gasolina na Terra, e como isso se parece? Um problema insuperável.

Mas novos esforços de pesquisa dizem que há esperança se nos comprometermos com emissões líquidas de carbono zero até 2050 e substituir veículos que consomem gasolina por veículos elétricos, entre muitas outras soluções de energia limpa.

Para ajudar nossa nação a atingir esse objetivo, cientistas como William Chueh e David Shapiro estão trabalhando juntos para criar novas estratégias para projetar baterias mais seguras e de longa distância feitas de materiais sustentáveis e abundantes na Terra.

Chueh é professor associado de ciência e engenharia de materiais na Universidade de Stanford com o objetivo de redesenhar a bateria moderna de baixo para cima. Ele conta com ferramentas de última geração nas instalações de usuários científicos do Departamento de Energia dos EUA, como a Fonte de Luz Avançada (ALS) do Berkeley Lab e a Fonte de Luz de Radiação Síncrotron Stanford do SLAC - instalações síncrotron que geram feixes brilhantes de luz de raios X - para revelar a dinâmica molecular de materiais de bateria no trabalho.

Por quase uma década, Chueh colaborou com Shapiro, um cientista sênior da ALS e um dos principais especialistas em síncrotron - e juntos, seu trabalho resultou em novas técnicas impressionantes, revelando pela primeira vez como os materiais da bateria funcionam em ação, em tempo real , em escalas sem precedentes invisíveis a olho nu.

Eles discutem seu trabalho pioneiro nesta sessão de perguntas e respostas.

P:O que despertou seu interesse na pesquisa de armazenamento de bateria/energia? Chueh:Meu trabalho é quase inteiramente orientado pela sustentabilidade. Envolvi-me na pesquisa de materiais energéticos quando era estudante de pós-graduação no início dos anos 2000 – estava trabalhando na tecnologia de células de combustível. Quando entrei em Stanford em 2012, ficou óbvio para mim que o armazenamento de energia escalável e eficiente é crucial.

Hoje, estou muito animado ao ver que a transição energética dos combustíveis fósseis está se tornando uma realidade e que está sendo implementada em uma escala incrível.

Tenho três objetivos:Primeiro, estou fazendo uma pesquisa fundamental que estabelece as bases para permitir a transição energética, especialmente em termos de desenvolvimento de materiais. Em segundo lugar, estou treinando cientistas e engenheiros de classe mundial que irão ao mundo real para resolver esses problemas. E, em terceiro lugar, estou pegando a ciência fundamental e traduzindo-a para uso prático por meio do empreendedorismo e da transferência de tecnologia.

Espero que isso dê a você uma visão abrangente do que me motiva e do que eu acho que é preciso para fazer a diferença:é o conhecimento, as pessoas e a tecnologia.

Shapiro:Minha formação é em óptica e espalhamento coerente de raios-X, então quando comecei a trabalhar na ALS em 2012, as baterias não estavam realmente no meu radar. Fui encarregado de desenvolver novas tecnologias para microscopia de raios X de alta resolução espacial, mas isso rapidamente levou às aplicações e a tentar descobrir o que os pesquisadores do Berkeley Lab e outros estão fazendo e quais são suas necessidades.

Na época, por volta de 2013, havia muito trabalho no ALS usando várias técnicas que exploram a sensibilidade química dos raios X suaves para estudar as transformações de fase em materiais de bateria, fosfato de ferro-lítio (LiFePO4), em particular, entre outros.

Fiquei realmente impressionado com o trabalho de Will, bem como com Wanli Yang, Jordi Cabana (ex-cientista da área de tecnologias de energia do Berkeley Lab (ETA) que agora é professor associado da Universidade de Illinois Chicago), e outros cujo trabalho também construiu fora do trabalho dos pesquisadores da ETA Robert Kostecki e Marca Doeff.

Eu não sabia nada sobre baterias na época, mas o impacto científico e social dessa área de pesquisa rapidamente se tornou aparente para mim. A sinergia da pesquisa no Berkeley Lab também me pareceu muito profunda, e eu queria descobrir como contribuir para isso. So I started to reach out to people to see what we could do together.

As it turned out, there was a great need to improve the spatial resolution of our battery materials measurements and to look at them during cycling—and Will and I have been working on that for nearly a decade now.

Q:Will, as a battery scientist, what would you say is the biggest challenge to making better batteries? Chueh:Batteries have on the order of 10 metrics that you have to co-optimize at the same time. It's easy to make a battery that's good on maybe five out of the 10, but to make a battery that's good in every metric is very immensely challenging.

For example, let's say you want a battery that is energy dense so you can drive an electric car for 500 miles per charge. You may want a battery that charges in 10 minutes. And you may want a battery that lasts 20 years. You also want a battery that never explodes. But it's hard to meet all of these metrics at once.

What we're trying to do is understand how we can create a single battery technology that is safe, long-lasting, and can be charged in 10 minutes.

And those are the fundamental insights that our experiments at Berkeley Lab's Advanced Light Source are trying to do:To uncover those unexplained tradeoffs so that we can go beyond today's design rules, which would enable us to identify new materials and new mechanisms so that we can free ourselves from those restrictions.

Q:What unique capabilities does the ALS offer that have helped to push the boundaries of battery or energy storage research? Chueh:In order to understand what's going on, we need to see it. We need to make observations. A key philosophy of my group is to embrace the dynamics and the heterogeneity of battery materials. A battery material is not like a rock. It's not static. You are charging and discharging it every day for your phones and every week for your electric cars. You're not going to understand how a car works by not driving it.

The second part is that heterogeneous battery materials are extremely length spanning. A battery cell is typically a few centimeters tall, but in order to understand what's going on inside the battery—and I have beautiful images for this—you want to see all the way down to the nanoscale and to the atomic scale. That's about 10 orders of magnitude of length.

What the Advanced Light Source empowers scientists like me to be able to do is to embrace the heterogeneity and dynamics of a battery in very unprecedented ways:We can measure very slow processes. We can measure very fast processes. We can measure things at the scale of many hundreds of microns (millionths of a meter). We can measure things at the nanoscale (billionth of a meter). All with one amazing tool at Berkeley Lab.

Shapiro:Scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM) is a very popular synchrotron-based method. Most synchrotrons around the world have at least one STXM instrument while the ALS has three—and a fourth is on the way through the ALS Upgrade (ALS-U) project.

I think a few things make our program unique. First, we have a portfolio of instruments with specializations. One is optimized for light element spectroscopy so an element like oxygen, which is a critical ingredient in battery chemistry, can be precisely characterized.

Another instrument specializes in mapping chemical composition at very high spatial resolution. We have the highest spatial resolution X-ray microscopy in the world. This is very powerful for zooming in on the chemical reactions happening within a battery's individual nanoparticles and interfaces.

Our third instrument specializes in "operando" measurements of battery chemistry, which you need in order to really understand the physical and chemical evolution that occurs during battery cycling.

We have also worked hard to develop synergies with other facilities at Berkeley Lab. For instance, our high-resolution microscope uses the same sample environments as the electron microscopes at the Molecular Foundry, Berkeley Lab's nanoscience user facility—so it has become feasible to probe the same active battery environment with both X-rays and electrons. Will has used this correlative approach to study relationships between chemical states and structural strain in battery materials. This has never been done before at the length scales we have access to, and it provides new insight.

Q:How will the ALS Upgrade project advance next-gen energy storage technologies? What will the upgraded ALS offer battery/energy-storage researchers that will be unique to Berkeley Lab? Shapiro:The upgraded ALS will be unique for a few reasons as far as microscopy is concerned. First, it will be the brightest soft X-ray source in the world, providing 100 times more X-rays on th sample than what we have today. Scanning microscopy techniques will benefit from such high brightness.

This is both a huge opportunity and a huge challenge. We can use this brightness to measure the data we get today—but doing this 100 times faster is the challenging part.

Such new capabilities will give us a much more statistically accurate look at battery structure and function by expanding to larger length scales and smaller time scales. Alternatively, we could also measure data at the same rate as today but with about three times finer spatial resolution, taking us from about 10 nanometers to just a few nanometers. This is a very important length scale for materials science, but today it's just not accessible by X-ray microscopy.

Another thing that will make the upgraded ALS unique is its proximity to expertise at the Molecular Foundry; other science areas such as the Energy Technologies Area; and current and future energy research hubs based at Berkeley Lab. This synergy will continue to drive energy storage research.

Chueh:In battery research, one of the challenges we have right now is that we have so many interesting problems to solve, but it takes hours and days to do just one measurement. The ALS-U project will increase the throughput of experiments and allow us to probe materials at higher resolution and smaller scales. Altogether, that adds up to enabling new science. Years ago, I contributed to making the case for ALS-U, so I couldn't be prouder to be part of that—I'm very excited to see the upgraded ALS come online so we can take advantage of its exciting new capabilities to do science that we cannot do today.