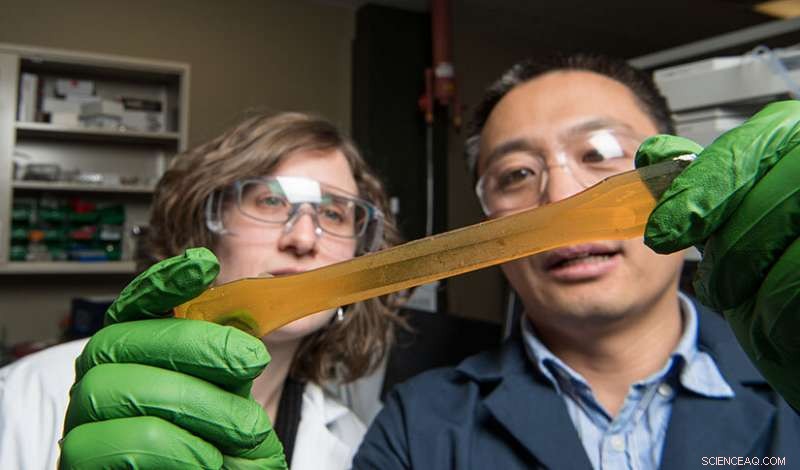

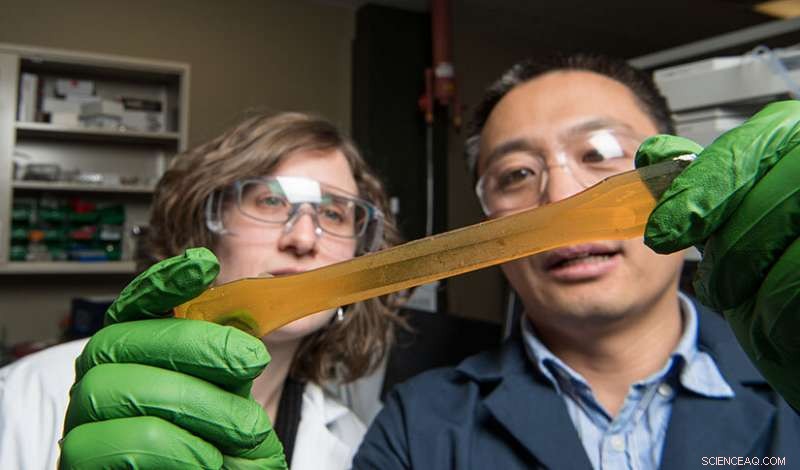

p Uma fórmula renovável inovadora - o pesquisador do NREL Tao Dong (à direita) e a ex-estagiária Stephanie Federle (à esquerda) examinam de base biológica, resina de poliuretano não tóxica, uma alternativa promissora ao poliuretano convencional. Crédito:Dennis Schroeder, NREL

p Uma fórmula renovável inovadora - o pesquisador do NREL Tao Dong (à direita) e a ex-estagiária Stephanie Federle (à esquerda) examinam de base biológica, resina de poliuretano não tóxica, uma alternativa promissora ao poliuretano convencional. Crédito:Dennis Schroeder, NREL

p Sem isso, o mundo pode ser um pouco menos macio e um pouco menos quente. Nossas roupas recreativas podem derramar menos água. As palmilhas de nossos tênis podem não fornecer o mesmo suporte terapêutico para o arco. O grão da madeira em móveis acabados pode não "estalar". p De fato, poliuretano - um plástico comum em aplicações que variam de espumas pulverizáveis a adesivos e fibras sintéticas de roupas - tornou-se um grampo do século 21, adicionando conveniência, conforto, e até mesmo a beleza em vários aspectos da vida cotidiana.

p A versatilidade do material, que atualmente é feito em grande parte de derivados de petróleo, fez do poliuretano o plástico preferido para uma variedade de produtos. Hoje, mais de 16 milhões de toneladas de poliuretano são produzidas globalmente a cada ano.

p "Poucos aspectos de nossas vidas não são tocados pelo poliuretano, "refletiu Phil Pienkos, um químico que recentemente se aposentou do Laboratório Nacional de Energia Renovável (NREL) após quase 40 anos de pesquisa.

p Mas Pienkos - que construiu uma carreira pesquisando novas maneiras de produzir combustíveis e materiais de base biológica - disse que há um impulso crescente para repensar como o poliuretano é produzido.

p "Os métodos atuais dependem amplamente de produtos químicos tóxicos e petróleo não renovável, "ele disse." Queríamos desenvolver um novo plástico com todas as propriedades úteis do poli convencional, mas sem os custosos efeitos colaterais ambientais. "

p Foi possível? Os resultados do laboratório são um retumbante sim.

p Por meio de uma nova química que usa recursos não tóxicos como óleo de linhaça, graxa residual, ou mesmo algas, Pienkos e seu colega do NREL Tao Dong, um especialista em engenharia química, desenvolveram um método inovador para a produção de poliuretano renovável sem precursores tóxicos.

p É um avanço com potencial para tornar o mercado mais verde para produtos que vão desde calçados, para automóveis, para colchões, e além.

p Mas, para entender o peso total da realização, é útil olhar para trás e ver como o avanço científico aconteceu, uma história que foge dos fundamentos químicos do poliuretano convencional, para o laboratório de algas, onde uma ideia para uma nova química surgiu pela primeira vez, e abre seu caminho para novas parcerias corporativas que definem o cenário para um futuro promissor de comercialização.

p

Uma questão de química

p Quando o poliuretano se tornou comercialmente disponível pela primeira vez na década de 1950, ele cresceu rapidamente em popularidade para uso em vários produtos e aplicações. Isso foi em grande parte devido às propriedades dinâmicas e ajustáveis do material, bem como a disponibilidade e acessibilidade dos componentes à base de petróleo usados para fazê-lo.

p Por meio de um processo químico inteligente usando polióis e isocianatos - os blocos de construção básicos dos poliuretanos convencionais - os fabricantes poderiam adaptar suas formulações para produzir uma variedade impressionante de materiais de poliuretano, cada um com propriedades únicas e úteis.

p Produzindo a partir de um poliol de cadeia longa, por exemplo, pode produzir espumas flexíveis para um colchão macio. Outra formulação pode render um líquido rico que, quando espalhado na mobília, protege e revela a beleza inerente do grão da madeira. Um terceiro lote pode incluir dióxido de carbono (CO

2 ) para expandir o material, produzindo uma espuma pulverizável que seca em um isolamento rígido e poroso, perfeito para manter o calor em uma casa.

p "Essa é a beleza do isocianato, "disse Dong ao refletir sobre o poliuretano convencional, "sua capacidade de formar espumas."

p Mas Dong disse que os isocianatos trazem desvantagens significativas, também. Embora esses produtos químicos tenham taxas de reatividade rápidas, tornando-os altamente adaptáveis a muitas aplicações da indústria, eles também são altamente tóxicos, e eles são produzidos a partir de uma matéria-prima ainda mais tóxica, fosgênio. Quando inalado, os isocianatos podem levar a uma série de efeitos adversos à saúde, como pele, olho, e irritação na garganta, asma, e outros problemas pulmonares graves.

p “Se produtos contendo poliuretanos convencionais forem queimados, esses isocianatos são volatilizados e liberados na atmosfera, "Pienkos acrescentou. Mesmo simplesmente pulverizando poliuretano para uso como isolamento, Pienkos disse, pode aerossolizar isocianato, exigindo que os trabalhadores tomem precauções cuidadosas para proteger sua saúde.

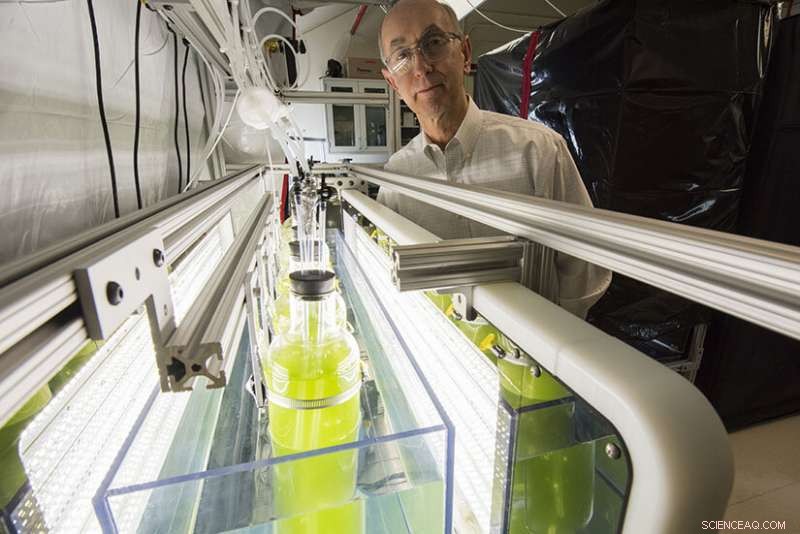

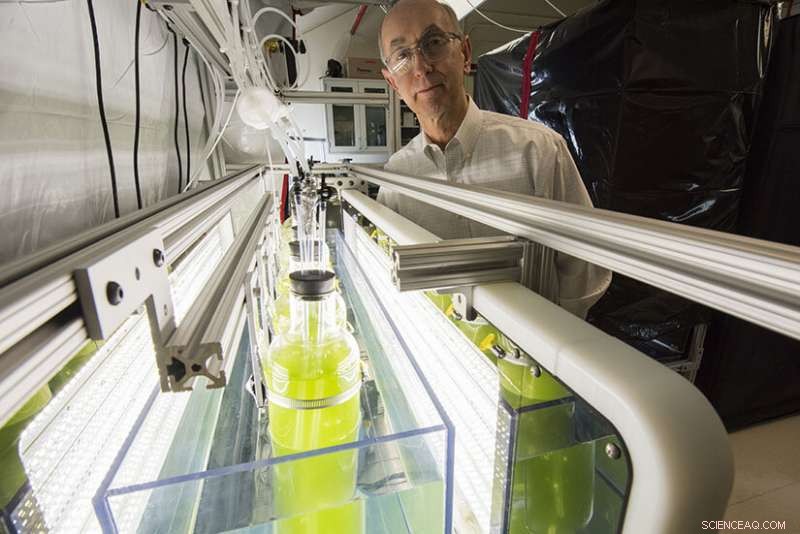

p Aposentado recentemente, Phil Pienkos (na foto) fundou uma nova empresa, Polaris Renewables, para ajudar a acelerar a comercialização do novo poliuretano, uma ideia que surgiu originalmente de sua pesquisa de biocombustíveis de algas no NREL. Crédito:Dennis Schroeder, NREL

p Aposentado recentemente, Phil Pienkos (na foto) fundou uma nova empresa, Polaris Renewables, para ajudar a acelerar a comercialização do novo poliuretano, uma ideia que surgiu originalmente de sua pesquisa de biocombustíveis de algas no NREL. Crédito:Dennis Schroeder, NREL

p To try and tackle these and other issues—such as reliance on petrochemicals—scientists from labs around the world have begun looking for new ways to synthesize polyurethane using bio-based resources. But these efforts have largely had mixed results. Some lacked the performance needed for industry applications. Others were not completely renewable.

p The challenge to improve polyurethane, então, remained ripe for innovation.

p "We can do better than this, " thought Pienkos five years ago when he first encountered the predicament. Energized by the opportunity, he joined with Dong and Lieve Laurens, also of NREL, on a search for a better polyurethane chemistry.

p

Rethinking the Building Blocks of Polyurethane

p The idea grew from a seemingly unrelated laboratory problem:lowering the cost of algae biofuels. As with many conventional petrochemical refining processes, biofuel refiners look for ways to use the coproducts of their processes as a source of revenue.

p The question becomes much the same for algae biorefining. Can the waste lipids and amino acids from the process become ingredients for a prized recipe for polyurethane that is both renewable and nontoxic?

p For Dong, answering the question at the basic chemical level was the easy part—of course they could. Scientists in the 1950s had shown it was possible to synthesize polyurethane from non-isocyanate pathways.

p The real challenge, Dong said, was figuring out how to speed up that reaction to compete with conventional processes. He needed to produce polymers that performed at least as well as conventional materials, a major technical barrier to commercializing bio-based polyurethanes.

p "The reactivity of the non-isocyanate, bio-based processes described in the literature is slower, " Dong explained. "So we needed to make sure we had reactivity comparable to conventional chemistry."

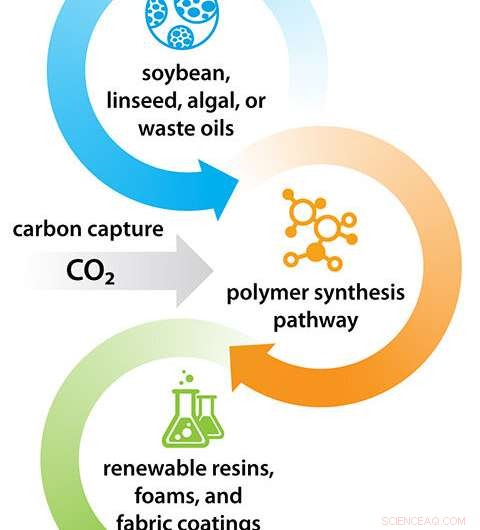

p NREL's process overcomes the barrier by developing bio-based formulas through a clever chemical process. It begins with an epoxidation process, which prepares the base oil—anything from canola oil or linseed oil to algae or food waste—for further chemical reactions. By reacting these epoxidized fatty acids with CO

2 from the air or flue gas, carbonated monomers are produced. Por último, Dong combines the carbonated monomers with diamines (derived from amino acids, another bio-based source) in a polymerization process that yields a material that cures into a resin—non-isocyanate polyurethane.

p By replacing petroleum-based polyols with select natural oils, and toxic isocyanates with bio-based amino acids, Dong had managed to synthesize polymers with properties comparable to conventional polyurethane. Em outras palavras, he had developed a viable renewable, nontoxic alternative to conventional polyurethane.

p And the chemistry had an added environmental benefit, também.

p "As much of 30% by weight of the final polymer is CO

2 , " Pienkos said, adding that the numbers are even more impressive when considering the CO

2 absorbed by the plants or algae used to create the oils and amino acids in the first place.

p CO

2 , a ubiquitous greenhouse gas, is often considered an unfortunate waste product of various industrial processes, prompting many companies to look for ways to absorb it, eliminate it, or even put it to good use as a potential source of profit. By incorporating CO

2 into the very structure of their polyurethane, Pienkos and Dong had provided a pathway for boosting its value.

p "That means less raw material per pound of polymer, custo mais baixo, and a lower overall carbon footprint, " Pienkos continued. "It looks to us that this offers remarkable sustainability opportunities."

p

A Sought-After Renewable Solution Finds Its Commercial Feet

p The next step was to see if the process could be commercialized, scaled up to meet the demands of the market.

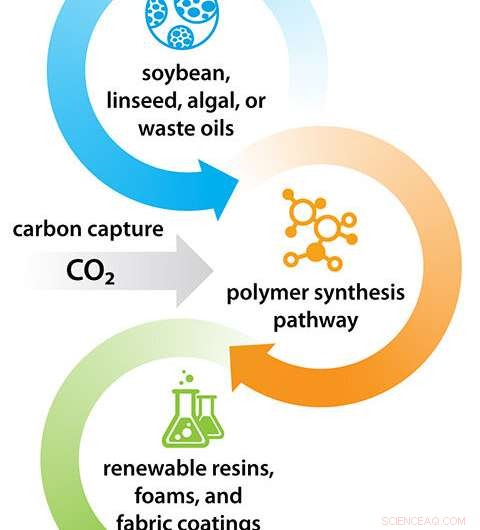

p The building blocks of poly—NREL's chemistry reacts natural oils with readily available carbon dioxide to produce renewable, nontoxic polyurethanes—a pathway for creating a variety of green materials and products. Crédito:Laboratório Nacional de Energia Renovável

p The building blocks of poly—NREL's chemistry reacts natural oils with readily available carbon dioxide to produce renewable, nontoxic polyurethanes—a pathway for creating a variety of green materials and products. Crédito:Laboratório Nacional de Energia Renovável

p Afinal, renewable or not, polyurethane needs to demonstrate the properties that consumers expect from brand-name products. The process to create it must also match companies' manufacturing processes, allowing them to "drop in" the new material without prohibitively costly upgrades to facilities or equipment.

p "That's why we need to work with industry partners, " Dong explained, "to make sure our research aligns with their manufacturing processes."

p In the two short years since Pienkos and Dong first demonstrated the viability of producing fully renewable, nontoxic polyurethane, several companies have already contributed resources and research partnerships in the push for its commercialization.

p A 2020 U.S. Department of Energy Technology Commercialization Fund award, por exemplo, brought in $730, 000 of federal funding to help develop the technology, as well as matching "in kind" cost share from the outdoor clothing company Patagonia, the mattress company Tempur Sealy, and a start-up biotechnology company called Algix.

p And Pienkos says companies from other industries have shown preliminary interest, também. "These companies believe there is promise in this, " ele disse.

p Their interest could partly be due to the tunability of Pienkos and Dong's approach, which lets them, much like conventional methods, create polymers that match industry standards.

p "We've demonstrated that the chemistry is tunable, " Dong said. "We can control the final performance through our approach."

p By controlling the epoxidation process or amount of carbonization, por exemplo, the process can be suited to meet the performance needs of a product. That may give the outsoles of a pair of running shoes enough flexibility and strength to endure many miles pounding into hot or cold asphalt. Or it may give a mattress a balance of stiffness and support.

p "It's got regulation push. It's got market pull. It's got the potential to compete with non-renewables on the basis of cost. It's got a lower carbon footprint. It's got everything, " Pienkos said of the opportunities for commercialization. "This became the most exciting aspect of my career at NREL. Então, when I retired, I decided that I want to make this real. I want to see this technology actually make it into the marketplace."

p After retiring last April, Pienkos went on to establish a company, Polaris Renewables, to help accelerate the commercialization of the novel polyurethane. Então, while he continues with his responsibilities as an NREL emeritus researcher, he is also doing outreach to industry to find additional corporate partners, especially in the fashion industry through the international sustainability initiative Fashion for Good.

p "In the fashion industry, customers are demanding sustainability, " he explained. "They will pay something of a green premium if you can demonstrate a lower carbon footprint, better end of life disposition."

p De fato, for both Pienkos and Dong, the breakthrough in renewable, nontoxic polyurethane has become more than an exciting scientific venture. It offers the world a pathway for products that leave a lighter mark on the environment.

p "I think this is a great opportunity to solve the plastic pollution problem, " Dong said. "We need to save our environment, and part of that begins with making plastic renewable."

p Pienkos, também, thinks that a commercial success in this venture could be a catalyst that spurs further growth and further success in bringing renewable, greener products to the market.

p "This could be a success story for NREL, " he said. "A success here means a great deal to the world."

p Nesse caso, success might be measured in more than the affordability of the production process or the carbon uptake of the polyurethane chemistry. In a world with NREL's renewable, nontoxic polyurethane, success might be something we can truly feel in the durability of our clothing, in the comfort our shoes provide, or in the rejuvenation we feel after sleeping on a memory foam mattress.