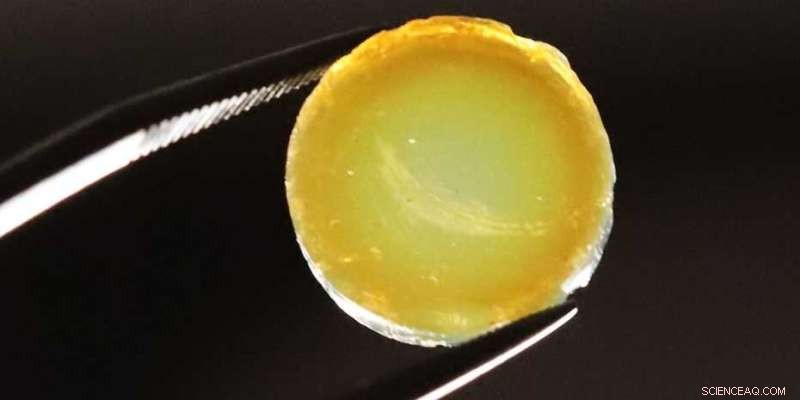

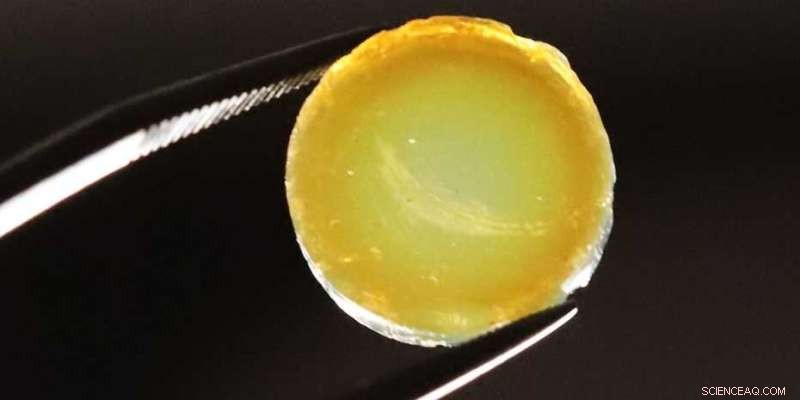

Um aerogel em forma de comprimido composto por paládio e nanopartículas de TiO2 dopadas com nitrogênio. Crédito:Markus Niederberger / ETH Zurique

Os aerogéis são materiais extraordinários que estabeleceram o Guinness World Records mais de uma dúzia de vezes, inclusive como os sólidos mais leves do mundo.

O professor Markus Niederberger, do Laboratório de Materiais Multifuncionais da ETH Zurich, vem trabalhando com esses materiais especiais há algum tempo. Seu laboratório é especializado em aerogéis compostos de nanopartículas semicondutoras cristalinas. "Somos o único grupo no mundo capaz de produzir esse tipo de aerogel com tamanha qualidade", afirma.

Um uso para aerogéis baseados em nanopartículas é como fotocatalisador. Eles são empregados sempre que uma reação química precisa ser ativada ou acelerada com a ajuda da luz solar – um exemplo é a produção de hidrogênio.

O material de escolha para fotocatalisadores é o dióxido de titânio (TiO

2 ), um semicondutor. Mas TiO

2 tem uma grande desvantagem:ele pode absorver apenas a porção UV da luz solar – apenas cerca de 5% do espectro. Para que a fotocatálise seja eficiente e útil industrialmente, o catalisador deve ser capaz de utilizar uma faixa mais ampla de comprimentos de onda.

Ampliando o espectro com dopagem de nitrogênio É por isso que o estudante de doutorado de Niederberger, Junggou Kwon, está procurando uma nova maneira de otimizar um aerogel feito de TiO

2 nanopartículas. E ela teve uma ideia brilhante:se o TiO

2 O aerogel de nanopartículas é "dopado" (para usar o termo técnico) com nitrogênio, de modo que os átomos de oxigênio individuais no material são substituídos por átomos de nitrogênio, o aerogel pode então absorver mais porções visíveis do espectro. O processo de dopagem deixa a estrutura porosa do aerogel intacta. O estudo sobre este método foi publicado recentemente na revista

Applied Materials &Interfaces .

Kwon produziu o aerogel pela primeira vez usando TiO

2 nanopartículas e pequenas quantidades do metal nobre paládio, que desempenha um papel fundamental na produção fotocatalítica de hidrogênio. Ela então colocou o aerogel em um reator e o infundiu com gás de amônia. Isso fez com que átomos de nitrogênio individuais se incorporassem na estrutura cristalina do TiO

2 nanopartículas.

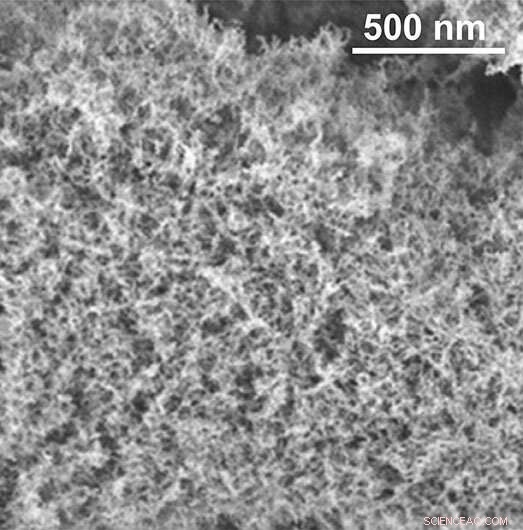

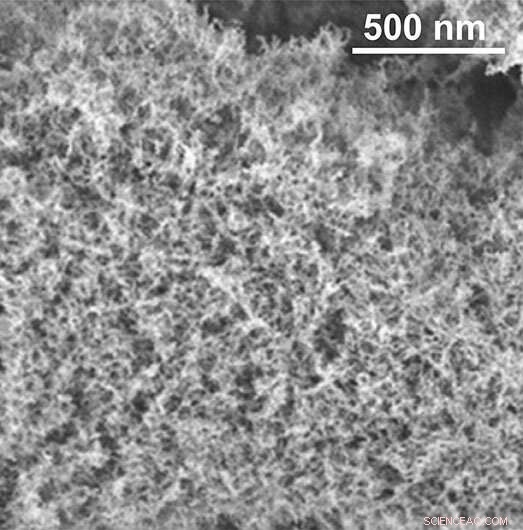

A estrutura interna esponjosa do aerogel. Crédito:Laboratório de Materiais Multifuncionais / ETH Zurich

Aergel modificado torna a reação mais eficiente Para testar se um aerogel modificado dessa maneira realmente aumenta a eficiência de uma reação química desejada – neste caso, a produção de hidrogênio a partir de metanol e água – Kwon desenvolveu um reator especial no qual colocou diretamente o monólito de aerogel. Ela então introduziu um vapor de água e metanol no aerogel no reator antes de irradiá-lo com duas luzes LED. The gaseous mixture diffuses through the aerogel's pores, where it is converted into the desired hydrogen on the surface of the TiO

2 and palladium nanoparticles.

Kwon stopped the experiment after five days, but up to that point, the reaction was stable and proceeded continuously in the test system. "The process would probably have been stable for longer," Niederberger says. "Especially with regard to industrial applications, it's important for it to be stable for as long as possible." The researchers were satisfied with the reaction's results as well. Adding the noble metal palladium significantly increased the conversion efficiency:using aerogels with palladium produced up to 70 times more hydrogen than using those without.

Increasing the gas flow This experiment served the researchers primarily as a feasibility study. As a new class of photocatalysts, aerogels offer an exceptional three-dimensional structure and offer potential for many other interesting gas-phase reactions in addition to hydrogen production. Compared to the electrolysis commonly used today, photocatalysts have the advantage that they could be used to produce hydrogen using only light rather than electricity.

Whether the aerogel developed by Niederberger's group will ever be used on a large scale is still uncertain. For example, there is still a question of how to accelerate the gas flow through the aerogel; at the moment, the extremely small pores hinder the gas flow too much. "To operate such a system on an industrial scale, we first have to increase the gas flow and also improve the irradiation of the aerogels," Niederberger says. He and his group are already working on these issues.

Aerogels are exceptional materials. They are extremely light and porous, and boast a huge surface area:one gram of the material can have a surface area of up to 1,200 square meters. Due to their transparency, aerogels have the appearance of "frozen smoke." They are excellent thermal insulators and so are used in aerospace applications and, increasingly, in the thermal insulation of buildings as well. However, their manufacture still requires a huge amount of energy, so the materials are expensive. The first aerogel was produced from silica by the chemist Samuel Kistler in 1931.

+ Explorar mais Novel strategy to fabricate 3D-MXene-based electrocatalyst for nitrogen reduction to ammonia