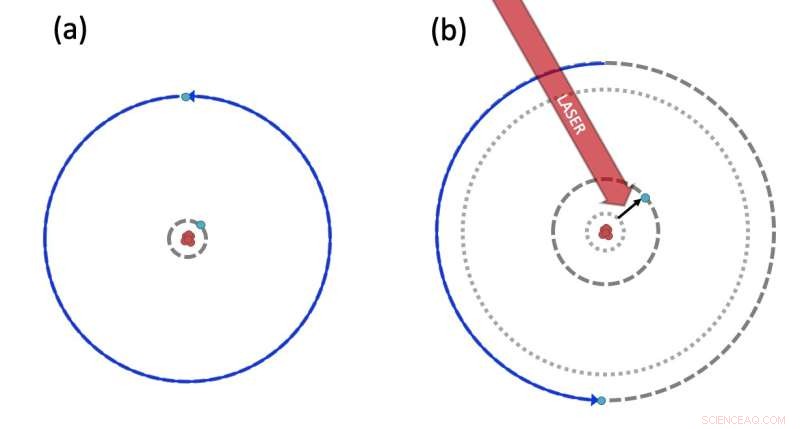

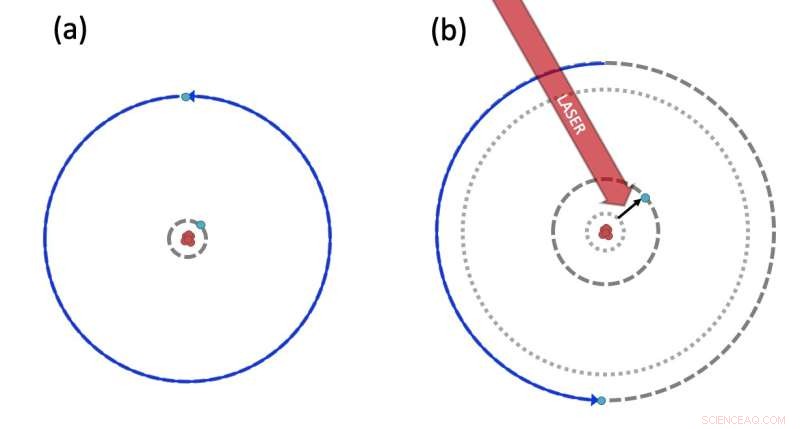

Na ausência do pulso de laser, o elétron de Rydberg orbita ao redor do núcleo em uma trajetória circular (seta azul). (b) Quando um pulso de laser transfere o elétron interno para uma órbita excitada, a força eletrostática empurra o elétron de Rydberg para uma órbita maior, onde ele gira mais lentamente. Crédito:Eva-Katharina Dietsche

Os átomos de Rydberg são átomos excitados que contêm um ou mais elétrons com um número quântico principal alto. Devido ao seu grande tamanho, interações dipolo-dipolo de longo alcance e forte acoplamento a campos externos, esses átomos provaram ser sistemas promissores para o desenvolvimento de tecnologias quânticas.

Apesar de suas vantagens, os físicos descobriram que os estados de Rydberg opticamente acessíveis tendem a ter uma vida útil curta, o que limita seu desempenho na tecnologia quântica. Uma possível solução para este problema poderia ser o uso de estados circulares de Rydberg, com tempos de vida mais longos, mas até agora sua detecção óptica tem se mostrado difícil.

Pesquisadores da ENS-University PSL, Sorbonne Université, Université Paris-Saclay e Universidade Federal de São Carlos demonstraram recentemente a manipulação coerente de um estado circular de Rydberg usando pulsos ópticos. Seus resultados, descritos em um artigo publicado na

Nature Physics , poderia abrir novas possibilidades para o desenvolvimento de uma plataforma híbrida de micro-ondas óptico para tecnologias quânticas.

"Os átomos alcalinos-terrosos são interessantes para a física de Rydberg, porque uma vez que o primeiro elétron está no estado de Rydberg, eles têm um segundo elétron que ainda pode ser usado para manipular o átomo com lasers", Sébastien Gleyzes, um dos pesquisadores que realizou o estudo, disse Phys.org. "No entanto, um problema é que, se a 'trajetória' do elétron de Rydberg (ou seja, sua função de onda) for muito elíptica, quando o segundo elétron é excitado com o laser, os dois elétrons podem colidir, o que leva à auto-ionização do átomo."

Em seus experimentos, Gleyzes e seus colegas usaram estados circulares de Rydberg, estados nos quais a trajetória/função de onda de um átomo de Rydberg está "a um círculo de distância" do núcleo iônico. Devido a essa organização circular, quando um segundo elétron dentro do átomo é excitado, há uma chance muito pequena de colidir com o primeiro.

"Nosso objetivo inicial era demonstrar que poderíamos excitar o segundo elétron sem que o átomo se ionizasse", disse Gleyzes. "No entanto, durante o experimento, observamos que a frequência de transição entre dois estados circulares de Rydberg era diferente dependendo se o segundo elétron estava em um estado excitado ou não."

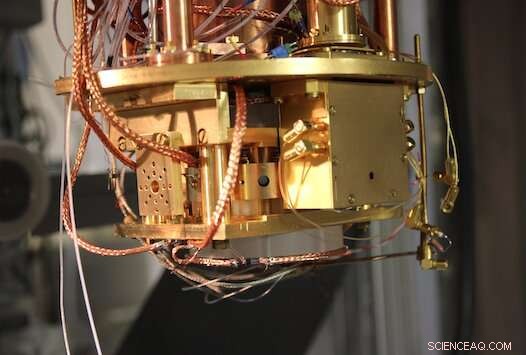

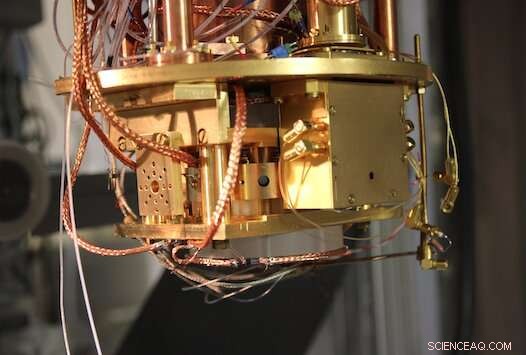

Imagem da montagem experimental antes de ser selada dentro do criostato e resfriada com hélio líquido. Crédito:Eva-Katharina Dietsche.

Essentially, the researchers found that even though the two valence electrons inside a Rydberg atom remain far away from each other in circular Rydberg states, they can still 'feel each other's presence' through the electrostatic force. They then showed that this 'electrostatic coupling' between the two electrons could be used to coherently manipulate the circular Rydberg state using optical pulses.

"In a classical picture, the frequency at which the Rydberg electron rotates depends on the state of the ionic core electron (let's call it 'up' or 'down')," Gleyzes explained. "We prepared the electron at given position on the orbit and waited for a time T such that the Rydberg electron makes an integer number of rotation if the ionic core is in 'down'. To optically change the state of the Rydberg electron, we transiently send the ionic core electron into other state ('up') with a laser pulse."

By sending the ionic core electron into the second desired state, the researchers slowed down the motion of the electron, which ultimately ends up on the other side of the orbit at the end of the waiting time (i.e., T). In other words, they were able to control the state of the Rydberg electron (which fluctuated between one side and the other of the orbit) by applying or removing a laser pulse.

"We thought that the alkaline earth Rydberg atoms would be interesting because one electron would be used for the quantum processes and the other electron would be used to control the motion of the atom (cool the atom or trap the atom)," Gleyzes said. "Before our study, though, we thought that they would work independently."

The technique to optically manipulate alkaline-earth circular Rydberg states introduced by this team of researchers could open interesting possibilities for the development of quantum technology. In fact, their work is the first to show that the two valence electrons inside alkaline-earth Rydberg atoms are not entirely independent, thus scientists could use one of them to manipulate the other or to detect the other's states.

"The possibility of conditioning the fluorescence of the ionic core electron to the state of the Rydberg electron is extremely promising, for instance if one wants to measure the state of the Rydberg electron non-destructively," Gleyzes added. "Our team's long-term goal is to build a quantum simulator based on the circular states of alkaline-earth atoms."

+ Explorar mais First successful laser trapping of circular Rydberg atoms

© 2022 Science X Network