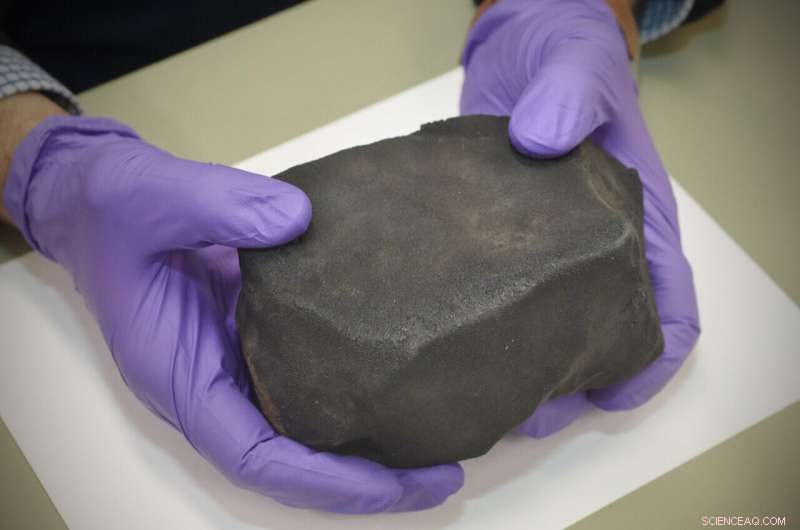

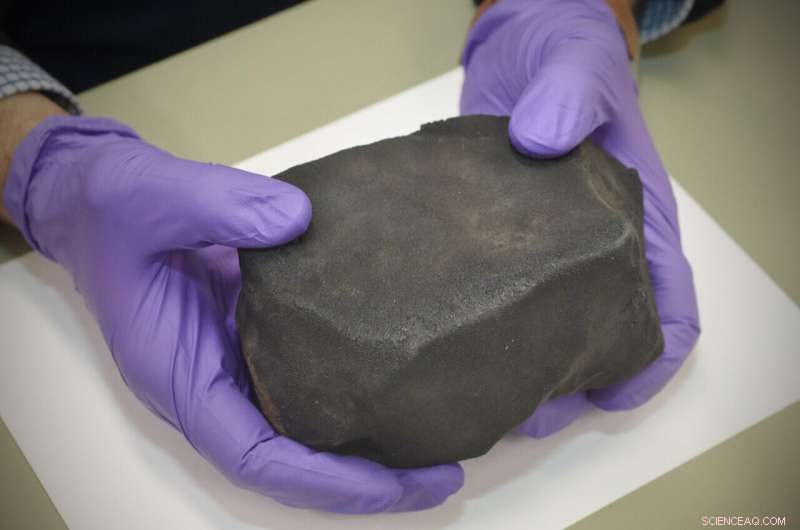

A massa principal do meteorito Aguas Zarcas no Museu do Campo. Crédito:John Weinstein, Museu Field

Em 2019, a espaçonave OSIRIS-REx da NASA enviou imagens de um fenômeno geológico que ninguém havia visto antes:seixos estavam voando da superfície do asteroide Bennu. O asteróide parecia estar disparando enxames de rochas do tamanho de mármore. Os cientistas nunca tinham visto esse comportamento de um asteroide antes, e é um mistério exatamente por que isso acontece. Mas em um novo artigo em

Nature Astronomy , pesquisadores mostram a primeira evidência desse processo em um meteorito.

“É fascinante ver algo que acabou de ser descoberto por uma missão espacial em um asteroide a milhões de quilômetros da Terra e encontrar um registro do mesmo processo geológico na coleção de meteoritos do museu”, diz Philipp Heck, curador do Robert A. Pritzker de Meteoritics no Field Museum de Chicago e autor sênior do livro

Nature Astronomy estudar.

Meteoritos são pedaços de rocha que caem do espaço sideral para a Terra; eles podem ser feitos de pedaços de luas e planetas, mas na maioria das vezes, eles são pedaços quebrados de asteróides. O meteorito Aguas Zarcas recebeu o nome da cidade costarriquenha onde caiu em 2019; chegou ao Field Museum como uma doação de Terry e Gail Boudreaux. Heck e seu aluno, Xin Yang, estavam preparando o meteorito para outro estudo quando notaram algo estranho.

"Estávamos tentando isolar minerais muito pequenos do meteorito congelando-o com nitrogênio líquido e descongelando-o com água morna, para quebrá-lo", diz Yang, estudante de pós-graduação do Field Museum e da Universidade de Chicago e o primeiro pesquisador do artigo. autor. "Isso funciona para a maioria dos meteoritos, mas este foi meio estranho - encontramos alguns fragmentos compactos que não se desfaziam."

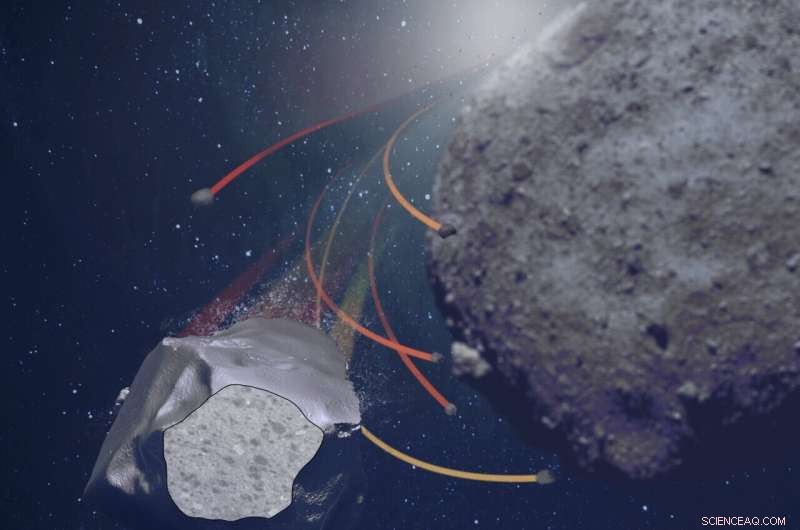

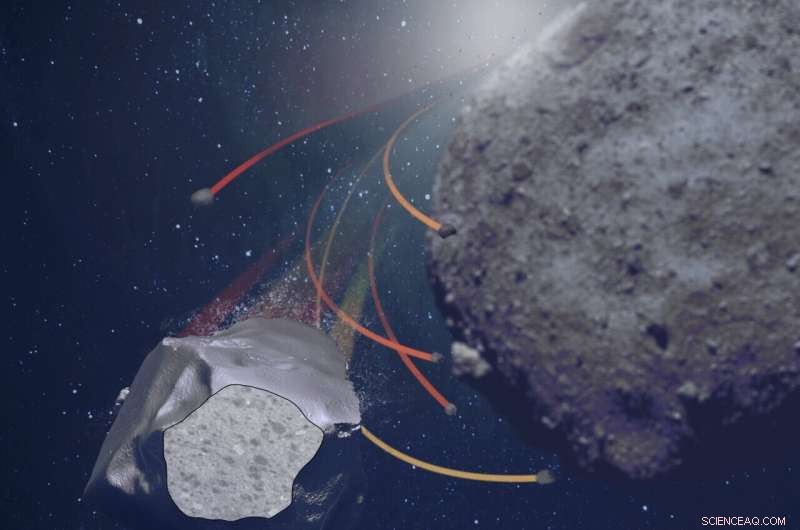

Representação artística do processo de mistura de seixos da matriz Aguas Zarcas. Fragmentos do tamanho de seixos são ejetados e redepositados na superfície do asteroide. Crédito:April I. Neander. Imagem do asteroide:NASA/Goddard/Universidade do Arizona.

Heck diz que encontrar pedaços de meteorito que não se desintegram não é algo inédito, mas os cientistas geralmente apenas dão de ombros e quebram o almofariz e o pilão. "Xin tinha uma mente muito aberta, ele disse:'Eu não vou esmagar essas pedrinhas em areia, isso é interessante'", diz Heck. Em vez disso, os pesquisadores elaboraram um plano para descobrir o que eram essas pedrinhas e por que elas eram tão resistentes à quebra.

“Fizemos tomografias computadorizadas para ver como os seixos se comparam às outras rochas que compõem o meteorito”, diz Heck. "O que chamou a atenção é que esses componentes foram todos esmagados - normalmente, seriam esféricos - e todos tinham a mesma orientação. Todos foram deformados na mesma direção, por um processo." Algo tinha acontecido com os seixos que não aconteceu com o resto da rocha ao redor deles.

Pebbles ejected off the surface of asteroid Bennu were observed frequently by NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft. This observation inspired this study. Credit:NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona/Lockheed Martin.

"This was exciting, we were very curious about what it meant," says Yang.

The scientists had a clue, though, from the 2019 OSIRIS-REx findings. From there, they put together a hypothesis, which they supported with physical models. The asteroid underwent a high-speed collision, and the area of impact got deformed. That deformed rock eventually broke apart due to the huge temperature differences the asteroid experiences when it rotates, since the side facing the sun is more than 300° F warmer than the side facing away. "This constant thermal cycling makes the rock brittle, and it breaks apart into gravel," says Heck.

These pebbles are then ejected from the asteroid's surface. "We don't yet know what the process is that ejects the pebbles," says Heck— they might be dislodged by smaller impacts other space collisions, or they might just get released by the thermal stress the asteroid undergoes. But once the pebbles are disturbed, Heck says, "you don't need much to eject something— the escape velocity is very low." A recent study of Bennu revealed that its surface is loosely bound and behaves like popcorn in a bucket.

Sampling of the Aguas Zarcas meteorite at the Field Museum of Natural History. Credit:Drew Carhart, Field Museum

The pebbles then entered a very slow orbit around the asteroid, and eventually, they fell back down to its surface further away where there was no deformation. Then, Heck and Yang say, the asteroid underwent

another collision, the loose mixed pebbles on the surface got transformed into a solid rock. "It basically packed everything together, and this loose gravel became a cohesive rock," says Heck. The same impact may have dislodged the new rock, sending it careening into space. Eventually, that chunk fell to Earth as the Aguas Zarcas meteorite, carrying evidence of the pebble mixing.

This could explain the pebbles present in Aguas Zarcas, making the meteorite the first physical evidence of the geological process observed by OSIRIS-REx on Bennu. "It provides a new way of explaining the way that minerals on the surfaces of asteroids get mixed," says Yang.

That's a big deal, Heck says, because for a long time, scientists assumed that the main way that the minerals on the surfaces of asteroids get rearranged is through big crashes, which don't happen very often. "From OSIRIS-REx we know that these particle ejection events are much more frequent than these high-velocity impacts," says Heck, "so they probably play a more important role in determining the makeup of asteroids and meteorites."

Aguas Zarcas is the first meteorite to show signs of this behavior, but it's probably not the only one. "We would expect this in other meteorites," says Heck. "People just haven't looked for it yet."

+ Explorar mais 'Fireball' meteorite contains pristine extraterrestrial organic compounds