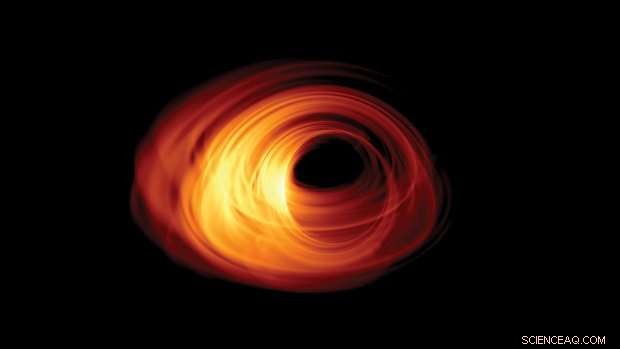

A sombra de um buraco negro rodeado por um anel de fogo em uma simulação genérica. Crédito:T. Bronzwaer, M. Moscibrodzka, H. Falcke Radboud University

Nas regiões sombrias dos buracos negros colidem duas teorias fundamentais que descrevem nosso mundo. Esses problemas podem ser resolvidos e os buracos negros realmente existem? Primeiro, podemos ter que ver um e os cientistas estão tentando fazer exatamente isso.

De todas as forças da física, há uma que ainda não entendemos:a gravidade.

A gravidade é onde a física fundamental e a astronomia se encontram, e onde as duas teorias mais fundamentais que descrevem nosso mundo - a teoria quântica e a teoria do espaço-tempo e da gravidade de Einstein (também conhecida como teoria da relatividade geral) - se chocam.

As duas teorias são aparentemente incompatíveis. E na maior parte, isso não é um problema. Ambos vivem em mundos distintos, onde a física quântica descreve o muito pequeno, e a relatividade geral descreve as escalas muito maiores.

Somente quando você chega a escalas muito pequenas e extrema gravidade, as duas teorias colidem, e de alguma forma, um deles errou. Pelo menos em teoria.

Mas existe um lugar no universo onde poderíamos realmente testemunhar esse problema ocorrendo na vida real e talvez até mesmo resolvê-lo:a borda de um buraco negro. Aqui, encontramos a gravidade mais extrema. Há apenas um problema - ninguém nunca realmente "viu" um buraco negro.

Então, o que é um buraco negro?

Imagine que todo o drama do mundo físico se desenrola no teatro do espaço-tempo, mas a gravidade é a única "força" que realmente modifica o teatro em que atua.

A força da gravidade governa o universo, mas pode nem mesmo ser uma força no sentido tradicional. Einstein descreveu isso como uma consequência da deformação do espaço-tempo. E talvez simplesmente não se encaixe no modelo padrão da física de partículas.

Quando uma estrela muito grande explode no final de sua vida, sua parte mais interna entrará em colapso sob sua própria gravidade, uma vez que não há mais combustível suficiente para sustentar a pressão que trabalha contra a força da gravidade (sim, afinal, a gravidade parece uma força, não é mesmo!).

A matéria entra em colapso e nenhuma força da natureza é conhecida para ser capaz de impedir esse colapso, sempre.

Em um tempo infinito, a estrela terá colapsado em um ponto infinitamente pequeno:uma singularidade - ou para dar-lhe outro nome, um buraco negro.

Claro, em um tempo finito, o núcleo estelar terá colapsado em algo de tamanho finito e isso ainda seria uma grande quantidade de massa em uma região insanamente pequena e ainda é chamado de buraco negro!

Os buracos negros não sugam tudo ao seu redor

Interessantemente, não é verdade que um buraco negro inevitavelmente atrairá tudo para dentro.

Na verdade, se você está orbitando uma estrela ou um buraco negro formado a partir de uma estrela, não faz diferença, contanto que a massa seja a mesma. A boa e velha força centrífuga e seu momento angular irão mantê-lo seguro e impedi-lo de cair.

Somente quando você dispara seus propulsores de foguetes gigantes para frear sua rotação, você vai começar a cair para dentro.

Contudo, uma vez que você cai em direção a um buraco negro, você será acelerado a velocidades cada vez mais altas, até que você finalmente alcance a velocidade da luz.

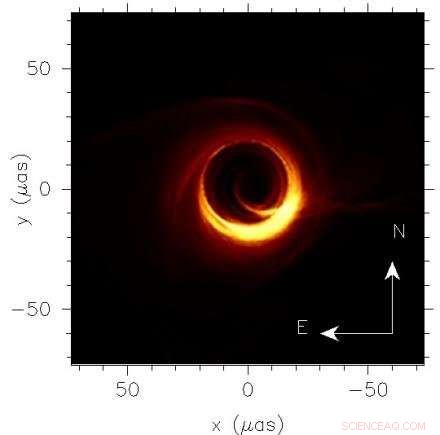

Imagem simulada conforme previsto para o preto supermassivo na galáxia M87 nas frequências observadas com o Event Horizon Telescope (230 GHz). Crédito:Moscibrodzka, Falcke, Shiokawa, Astronomia e Astrofísica, V. 586, p. 15, 2016, reproduzido com permissão © ESO

Por que a teoria quântica e a relatividade geral são incompatíveis?

Nesse ponto, tudo dá errado, pois de acordo com a relatividade geral, nada deve se mover mais rápido do que a velocidade da luz.

A luz é o substrato usado no mundo quântico para trocar forças e transportar informações no mundo macro. A luz determina o quão rápido você pode conectar causa e consequências.

Se você for mais rápido que a luz, você pode ver os eventos e mudar as coisas antes que aconteçam. Isso tem duas consequências:

Se isso é verdade e se e como a teoria da gravidade (ou da física quântica) precisa ser modificada é uma questão de intenso debate entre os físicos, e nenhum de nós pode dizer para que lado a discussão nos levará no final.

Os buracos negros ainda existem?

Claro, toda essa excitação só seria justificada, se buracos negros realmente existiam neste universo. Então, Eles?

No último século, surgiram fortes evidências de que certas estrelas binárias com intensas emissões de raios X são na verdade estrelas colapsadas em buracos negros.

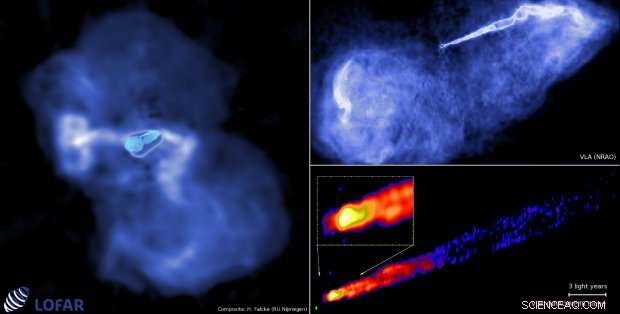

Além disso, nos centros das galáxias, muitas vezes encontramos evidências de enormes, concentrações escuras de massa. Podem ser versões supermassivas de buracos negros, possivelmente formado pela fusão de muitas estrelas e nuvens de gás que afundaram no centro de uma galáxia.

A evidência é convincente, mas circunstancial. Pelo menos as ondas gravitacionais nos permitiram 'ouvir' a fusão dos buracos negros, mas a assinatura do horizonte de eventos ainda é indescritível e, até agora, nunca realmente 'vimos' um buraco negro - eles simplesmente tendem a ser muito pequenos e muito distantes e, na maioria dos casos, sim, Preto...

Então, qual seria a aparência real de um buraco negro?

Se você pudesse olhar diretamente para um buraco negro, veria a escuridão mais escura, você pode imaginar.

Mas, os arredores imediatos de um buraco negro podem ser brilhantes à medida que os gases espiralam para dentro - diminuídos pelo arrasto dos campos magnéticos que carregam.

Devido ao atrito magnético, o gás vai aquecer até enormes temperaturas de até várias dezenas de bilhões de graus e começar a irradiar luz ultravioleta e raios-X.

Elétrons ultracaquecidos interagindo com o campo magnético do gás começarão a produzir intensa emissão de rádio. Assim, buracos negros podem brilhar e podem ser cercados por um anel de fogo que irradia em muitos comprimentos de onda diferentes.

Um anel de fogo com uma escuridão, centro escuro

Bem no centro, Contudo, o horizonte de eventos ainda espreita e, como uma ave de rapina, captura todos os fótons que se aproximam demais.

Radio images of the jet in the radio galaxy M87 – observed at lower resolution. The left frame is roughly 250, 000 light years across. Magnetic fields threading the supermassive black holes lead to the formation of a highly collimated jet that spits out hot plasma with speeds close to the speed of light . Credit:H. Falcke, Radboud university, with images from LOFAR/NRAO/MPIfR Bonn

Since space is bent by the enormous mass of a black hole, light paths will also be bent and even form into almost concentric circles around the black hole, like serpentines around a deep valley. This effect of circling light was calculated already in 1916 by the famous Mathematician David Hilbert only a few months after Albert Einstein finalised his theory of general relativity.

After orbiting the black hole multiple times, some of the light rays might escape while others will end up in the event horizon. Along this complicated light path, you can literally look into the black hole. The nothingness you see is the event horizon.

If you were to take a photo of a black hole, what you would see would be akin to a dark shadow in the middle of a glowing fog of light. Portanto, we called this feature the shadow of a black hole .

Interessantemente, the shadow appears larger than you might expect by simply taking the diameter of the event horizon. The reason is simply, that the black hole acts as a giant lens, amplifying itself.

Surrounding the shadow will be a thin 'photon ring' due to light circling the black hole almost forever. Further out, you would see more rings of light that arise from near the event horizon, but tend to be concentrated around the black hole shadow due to the lensing effect.

Fantasy or reality?

Is this pure fantasy that can only be simulated in a computer? Or can it actually be seen in practice? The answer is that it probably can.

There are two relatively nearby supermassive black holes in the universe which are so large and close, that their shadows could be resolved with modern technology.

These are the black holes in the center of our own Milky Way at a distance of 26, 000 lightyears with a mass of 4 million times the mass of the sun, and the black hole in the giant elliptical galaxy M87 (Messier 87) with a mass of 3 to 6 billion solar masses.

M87 is a thousand times further away, but also a thousand times more massive and a thousand times larger, so that both objects are expected to have roughly the same shadow diameter projected onto the sky.

Like seeing a grain of mustard in New York from Europe

Coincidentally, simple theories of radiation also predict that for both objects the emission generated near the event horizon would be emitted at the same radio frequencies of 230 GHz and above.

Most of us come across these frequencies only when we have to pass through a modern airport scanner but some black holes are continuously bathed in them.

The radiation has a very short wavelength of about one millimetre and is easily absorbed by water. For a telescope to observe cosmic millimetre waves it will therefore have to be placed high up, on a dry mountain, to avoid absorption of the radiation in the Earth's troposphere.

Effectively, you need a millimetre-wave telescope that can see an object the size of a mustard seed in New York from as far away as Nijmegen in the Netherlands. That is a telescope a thousand times sharper than the Hubble Space Telescope and for millimetre-waves this requires a telescope the size of the Atlantic Ocean or larger.

A virtual Earth-sized telescope

Felizmente, we do not need to cover the Earth with a single radio dish, but we can build a virtual telescope with the same resolution by combining data from telescopes on different mountains across the Earth.

The technique is called Earth rotation synthesis and very long baseline interferometry (VLBI). The idea is old and has been tested for decades already, but it is only now possible at high radio frequencies.

Layout of the Event Horizon Telescope connecting radio telescopes around the world (JCMT &SMA in Hawaii, AMTO in Arizona, LMT in Mexico, ALMA &APEX in Chile, SPT on the South Pole, IRAM 30m in Spain). The red lines are to a proposed telescope on the Gamsberg in Namibia that is still being planned. Credit:ScienceNordic / Forskerzonen. Compiled from images provided by the author

The first successful experiments have already shown that event horizon structures can be probed at these frequencies. Now high-bandwidth digital equipment and large telescopes are available to do this experiment on a large scale.

Work is already underway

I am one of the three Principal Investigators of the BlackHoleCam project. BlackHoleCam is an EU-funded project to finally image, measure and understand astrophysical black holes. Our European project is part of a global collaboration known as the Event Horizon Telescope consortium – a collaboration of over 200 scientists from Europe, the Americas, Asia, e a África. Together we want to take the first picture of a black hole.

In April 2017 we observed the Galactic Center and M87 with eight telescopes on six different mountains in Spain, Arizona, Havaí, México, Chile, and the South Pole.

All telescopes were equipped with precise atomic clocks to accurately synchronise their data. We recorded multiple petabytes of raw data, thanks to surprisingly good weather conditions around the globe at the time.

We are all excited about working with this data. Claro, even in the best of all cases, the images will never look as pretty as the computer simulations. Mas, at least they will be real and whatever we see will be interesting in its own right.

To get even better images telescopes in Greenland and France are being added. Além disso, we have started raising funds for additional telescopes in Africa and perhaps elsewhere and we are even thinking about telescopes in space.

A 'photo' of a black hole

If we actually succeed in seeing an event horizon, we will know that the problems we have in rhyming quantum theory and general relativity are not abstract problems, but are very real. And we can point to them in the very real shadowy regions of black holes in a clearly marked region of our universe.

This is perhaps also the place where these problems will eventually be solved.

We could do this by obtaining sharper images of the shadow, or maybe by tracing stars and pulsars as they orbit around black holes, through measuring spacetime ripples as black holes merge, or as is most likely, by using all of the techniques that we now have, juntos, to probe black holes.

A once exotic concept is now a real working laboratory

As a student, I wondered what to study:particle physics or astrophysics? After reading many popular science articles, my impression was that particle physics had already reached its peak. This field had established an impressive standard model and was able to explain most of the forces and the particles governing our world.

Astronomy though, had just started to explore the depths of a fascinating universe. There was still a lot to be discovered. And I wanted to discover something.

No fim, I chose astrophysics as I wanted to understand gravity. And since you find the most extreme gravity near black holes, I decided to stay as close to them as possible.

Hoje, what used to be an exotic concept when I started my studies, promises to become a very real and very much visible physics laboratory in the not too distant future.

Esta história foi republicada por cortesia da ScienceNordic, a fonte confiável de notícias científicas em inglês dos países nórdicos. Leia a história original aqui.