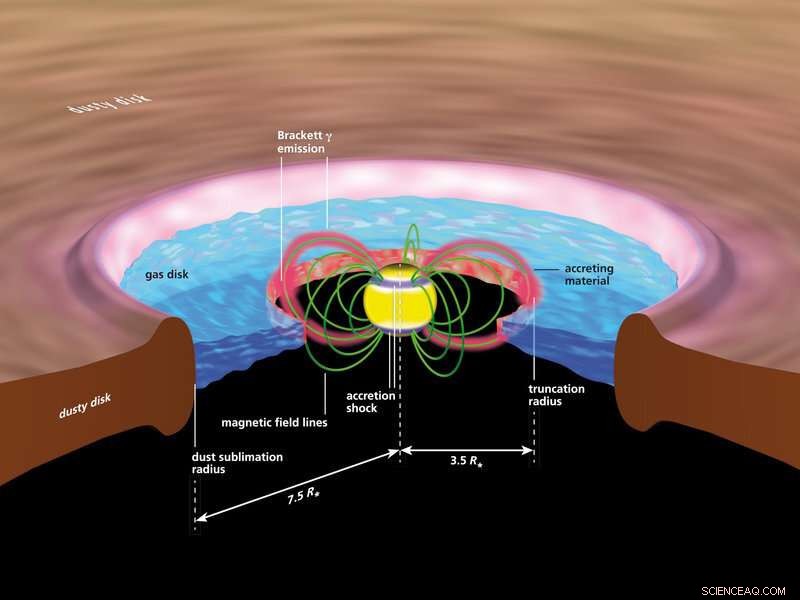

Impressão artística dos fluxos de gás quente que ajudam as estrelas jovens a crescer. Os campos magnéticos guiam a matéria do disco circunstelar circundante, o local de nascimento dos planetas, para a superfície da estrela, onde eles produzem intensas explosões de radiação. Crédito:A. Mark Garlick

Os astrônomos usaram o instrumento GRAVITY para estudar a vizinhança imediata de uma jovem estrela com mais detalhes do que nunca. Suas observações confirmam uma teoria de trinta anos sobre o crescimento de estrelas jovens:o campo magnético produzido pela própria estrela direciona o material de um disco de acreção circundante de gás e poeira para sua superfície. Os resultados, publicado hoje no jornal Natureza , ajudar os astrônomos a entender melhor como estrelas como o nosso Sol são formadas e como os planetas semelhantes à Terra são produzidos a partir dos discos que cercam esses bebês estelares.

Quando as estrelas se formam, eles começam relativamente pequenos e estão localizados nas profundezas de uma nuvem de gás. Ao longo das próximas centenas de milhares de anos, eles atraem mais e mais do gás circundante para si, aumentando sua massa no processo. Usando o instrumento GRAVITY, um grupo de pesquisadores que inclui astrônomos e engenheiros do Instituto Max Planck de Astronomia (MPIA), agora encontrou a evidência mais direta de como esse gás é canalizado para estrelas jovens:ele é guiado pelo campo magnético da estrela para a superfície em uma coluna estreita.

As escalas de comprimento relevantes são tão pequenas que mesmo com os melhores telescópios atualmente disponíveis, nenhuma imagem detalhada do processo é possível. Ainda, usando a mais recente tecnologia de observação, os astrônomos podem pelo menos colher algumas informações. Para o novo estudo, os pesquisadores usaram o poder de resolução incrivelmente alto do instrumento chamado GRAVIDADE. Ele combina quatro telescópios VLT de 8 metros do Observatório Europeu do Sul (ESO) no observatório Paranal no Chile em um telescópio virtual que pode distinguir pequenos detalhes tão bem quanto um telescópio com um espelho de 100 metros faria.

Usando GRAVITY, os pesquisadores foram capazes de observar a parte interna do disco de gás ao redor da estrela TW Hydrae. "Esta estrela é especial porque está muito perto da Terra, a apenas 196 anos-luz de distância, e o disco de matéria ao redor da estrela está diretamente voltado para nós, "diz Rebeca García López (Instituto Max Planck de Astronomia, Instituto de Estudos Avançados de Dublin e University College Dublin), autor principal e cientista principal deste estudo. "Isso o torna um candidato ideal para sondar como a matéria de um disco em formação de planeta é canalizada para a superfície estelar."

A observação permitiu aos astrônomos mostrar que a radiação infravermelha emitida por todo o sistema realmente se origina na região mais interna, onde o gás hidrogênio está caindo na superfície da estrela. Os resultados apontam claramente para um processo conhecido como acreção magnetosférica, isso é, matéria em queda guiada pelo campo magnético da estrela.

Nascimento estelar e crescimento estelar

Uma estrela nasce quando uma região densa dentro de uma nuvem de gás molecular entra em colapso sob sua própria gravidade, torna-se consideravelmente mais denso, aquece no processo, até que eventualmente a densidade e a temperatura na protoestrela resultante sejam tão altas que começa a fusão nuclear de hidrogênio em hélio. Para protoestrelas com até cerca de duas vezes a massa do Sol, os dez ou mais milhões de anos imediatamente antes da ignição da fusão nuclear próton-próton constituem a chamada fase T Tauri (em homenagem à primeira estrela observada deste tipo, T Tauri na constelação de Touro).

Estrelas que vemos nessa fase de desenvolvimento, conhecidas como estrelas T Tauri, brilhar muito forte, em particular na luz infravermelha. Esses chamados "objetos estelares jovens" (YSOs) ainda não atingiram sua massa final:eles estão rodeados pelos restos da nuvem da qual nasceram, em particular pelo gás que se contraiu em um disco circunstelar em torno da estrela. Nas regiões externas desse disco, poeira e gás se aglomeram e formam corpos cada vez maiores, que eventualmente se tornará planetas. Grandes quantidades de gás e poeira da região interna do disco, por outro lado, são desenhados na estrela, aumentando sua massa. Por último mas não menos importante, a intensa radiação da estrela expulsa uma porção considerável do gás como um vento estelar.

Diretrizes para a superfície:o campo magnético da estrela

Ingenuamente, pode-se pensar que o transporte de gás ou poeira em um enorme, gravitar corpo é fácil. Em vez de, acabou por não ser tão simples assim. Devido ao que os físicos chamam de conservação do momento angular, é muito mais natural para qualquer objeto - seja planeta ou nuvem de gás - orbitar uma massa do que cair direto sobre sua superfície. Uma razão pela qual alguma matéria, no entanto, consegue alcançar a superfície é o chamado disco de acreção, in which gas orbits the central mass. There is plenty of internal friction inside that continually allows some of the gas to transfer its angular momentum to other portions of gas and move further inward. Ainda, at a distance from the star of less than 10 times the stellar radius, the accretion process gets more complex. Traversing that last distance is tricky.

Thirty years ago, Max Camenzind, at the Landessternwarte Königstuhl (which has since become a part of the University of Heidelberg), proposed a solution to this problem. Stars typically have magnetic fields—those of our Sun, por exemplo, regularly accelerate electrically charged particles in our direction, leading to the phenomenon of Northern or Southern lights. In what has become known as magnetospheric accretion, the magnetic fields of the young stellar object guide gas from the inner rim of the circumstellar disk to the surface in distinct column-like flows, helping them to shed angular momentum in a way that allows the gas to flow onto the star.

In the simplest scenario, the magnetic field looks similar to that of the Earth. Gas from the inner rim of the disk would be funneled to the magnetic North and to the magnetic South pole of the star.

Checking up on magnetospheric accretion

Having a model that explains certain physical processes is one thing. Contudo, it is important to be able to test that model using observations. But the length scales in question are of the order of stellar radii, very small on astronomical scales. Até recentemente, such length scales were too small, even around the nearest young stars, for astronomers to be able to take a picture showing all relevant details.

Schematic representation of the process of magnetospheric accretion of material onto a young star. Magnetic fields produced by the young star carry gas through flow channels from the disk to the polar regions of the star. The ionized hydrogen gas emits intense infrared radiation. When the gas hits the star's surface, shocks occur that give rise to the star's high brightness. Credit:MPIA graphics department

First indication that magnetospheric accretion is indeed present came from examining the spectra of some T Tauri stars. Spectra of gas clouds contain information about the motion of the gas. For some T Tauri stars, spectra revealed disk material falling onto the stellar surface with velocities as high as several hundred kilometers per second, providing indirect evidence for the presence of accretion flows along magnetic field lines. In a few cases, the strength of the magnetic field close to a T Tauri star could be directly measured by a combining high-resolution spectra and polarimetry, which records the orientation of the electromagnetic waves we receive from an object.

Mais recentemente, instruments have become sufficiently advanced—more specifically:have reached sufficiently high resolution, a sufficiently good capability to discern small details—so as to allow direct observations that provide insights into magnetospheric accretion.

The instrument GRAVITY plays a key role here. It was developed by a consortium that includes the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, led by the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics. In operation since 2016, GRAVITY links the four 8-meter-telescopes of the VLT, located at the Paranal observatory of the European Southern Observatory (ESO). The instrument uses a special technique known as interferometry. The result is that GRAVITY can distinguish details so small as if the observations were made by a single telescope with a 100-m mirror.

Catching magnetic funnels in the act

In the Summer of 2019, a team of astronomers led by Jerome Bouvier of the University of Grenobles Alpes used GRAVITY to probe the inner regions of the T Tauri Star with the designation DoAr 44. It denotes the 44th T Tauri star in a nearby star forming region in the constellation Ophiuchus, catalogued in the late 1950s by the Georgian astronomer Madona Dolidze and the Armenian astronomer Marat Arakelyan. The system in question emits considerable light at a wavelength that is characteristic for highly excited hydrogen. Energetic ultraviolet radiation from the star ionizes individual hydrogen atoms in the accretion disk orbiting the star.

The magnetic field then influences the electrically charged hydrogen nuclei (each a single proton). The details of the physical processes that heat the hydrogen gas as it moves along the accretion current towards the star are not yet understood. The observed greatly broadened spectral lines show that heating occurs.

For the GRAVITY observations, the angular resolution was sufficiently high to show that the light was not produced in the circumstellar disk, but closer to the star's surface. Além disso, the source of that particular light was shifted slightly relative to the centre of the star itself. Both properties are consistent with the light being emitted near one end of a magnetic funnel, where the infalling hydrogen gas collides with the surface of the star. Those results have been published in an article in the journal Astronomia e Astrofísica .

Os novos resultados, which have now been published in the journal Natureza , go one step further. Nesse caso, the GRAVITY observations targeted the T Tauri star TW Hydrae, a young star in the constellation Hydra. They are based on GRAVITY observations of the T Tauri star TW Hydrae, a young star in the constellation Hydra. It is probably the best-studied system of its kind.

Too small to be part of the disk

With those observations, Rebeca García López and her colleagues have pushed the boundaries even further inwards. GRAVITY could see the emissions corresponding to the line associated with highly excited hydrogen (Brackett-γ, Brγ) and demonstrate that they stem from a region no more than 3.5 times the radius of the star across (about 3 million km, or 8 times the distance the distance between the Earth and the Moon).

This is a significant difference. According to all physics-based models, the inner rim of a circumstellar disk cannot possibly be that close to the star. If the light originates from that region, it cannot be emitted from any section of the disk. At that distance, the light also cannot be due to a stellar wind blown away by the young stellar object—the only other realistic possibility. Tomados em conjunto, what is left as a plausible explanation is the magnetospheric accretion model.

Qual é o próximo?

In future observations, again using GRAVITY, the researchers will try to get data that allows them a more detailed reconstruction of physical processes close to the star. "By observing the location of the funnel's lower endpoint over time, we hope to pick up clues as to how distant the magnetic North and South poles are from the star's axis of rotation, " explains Wolfgang Brandner, co-author and scientist at MPIA. If North and South Pole directly aligned with the rotation axis, their position over time would not change at all.

They also hope to pick up clues as to whether the star's magnetic field is really as simple as a North Pole–South Pole configuration. "Magnetic fields can be much more complicated and have additional poles, " explains Thomas Henning, Director at MPIA. "The fields can also change over time, which is part of a presumed explanation for the brightness variations of T Tauri stars."

All in all, this is an example of how observational techniques can drive progress in astronomy. Nesse caso, the new observational techniques embody in GRAVITY were able to confirm ideas about the growth of young stellar objects that were proposed as long as 30 years ago. And future observations are set to help us understand even better how baby stars are being fed.