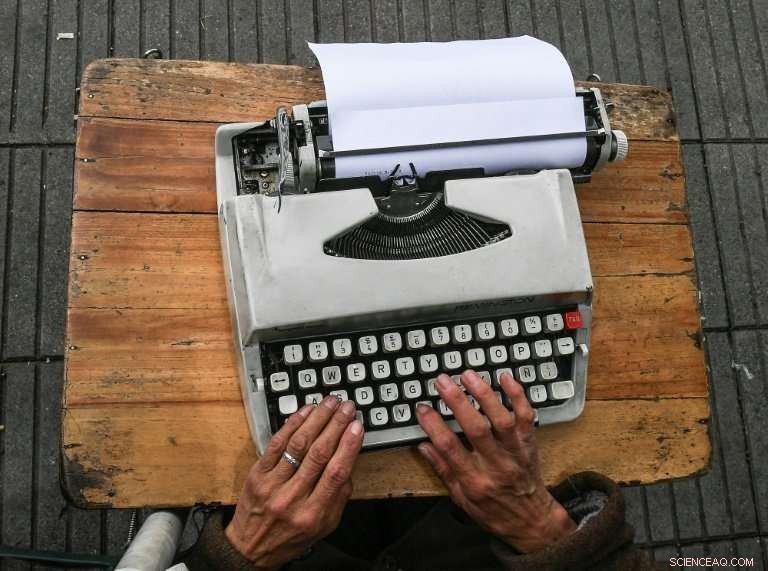

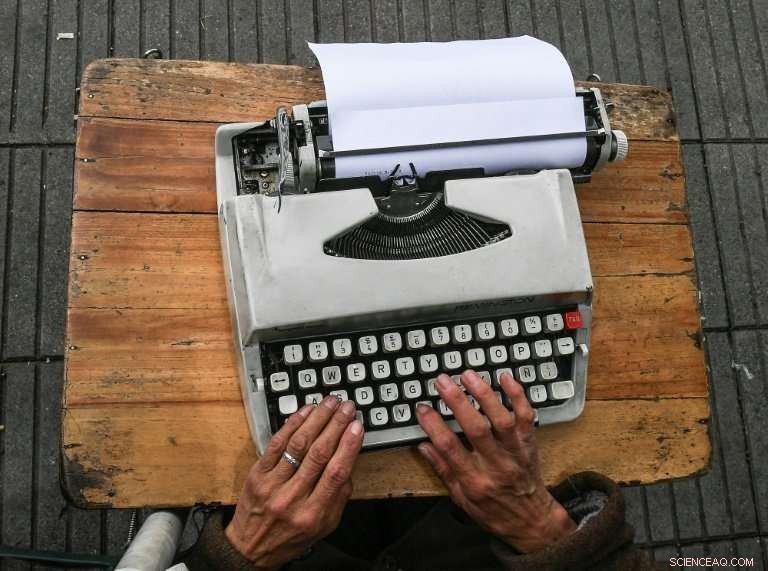

p Os balconistas de rua da Colômbia trabalham ao ar livre com suas máquinas de escrever empoleiradas em uma pequena mesa na frente deles

p Os balconistas de rua da Colômbia trabalham ao ar livre com suas máquinas de escrever empoleiradas em uma pequena mesa na frente deles

p Antes do dia de maio, Repórteres da AFP, equipes de vídeo e foto conversaram com homens e mulheres em todo o mundo cujos empregos estão se tornando cada vez mais raros, particularmente à medida que a tecnologia transforma as sociedades. p

Os últimos balconistas de rua de Bogotá

p Inserindo uma folha em branco em seu Remington Sperry, Candelaria Pinilla de Gomez começa a digitar. Um dos vendedores ambulantes de Bogotá, ela passou os últimos 40 anos digitando incontáveis milhares de documentos.

p 63 anos, ela é a única mulher entre os balconistas que montaram suas mesinhas na calçada de um moderno prédio de escritórios em Bogotá.

p Usando ternos, mas sem gravata, os escritores trabalham ao ar livre, sob um guarda-sol, sentados em uma cadeira de plástico com a máquina de escrever sobre os joelhos.

p Era uma vez, esses funcionários desempenharam um papel essencial - com escrituras públicas, documentos fiscais e contratos, todos passando por suas mãos.

p Pinilla de Gomez aprendeu o ofício com o marido quando eles chegaram à capital colombiana na década de 1960. Ele tinha uma fazenda "mas os guerrilheiros a tiraram dele, " ela diz.

p “Em Bogotá, ele me disse que eu deveria aprender a digitar ... e a soletrar. Ele me ensinou (o trabalho) e depois morreu. "

p Cesar Diaz, agora 68, orgulha-se de ser o pioneiro de um comércio que acabou por se tornar um "refúgio" para os reformados que procuram reforçar as suas mensalidades.

p Candelaria Pinilla de Gomez, 63, trabalha como balconista em Bogotá há cerca de 40 anos

p Candelaria Pinilla de Gomez, 63, trabalha como balconista em Bogotá há cerca de 40 anos

p Eles trabalham de segunda a sexta-feira e ganham menos de US $ 280, que é o salário mínimo.

p Até agora, eles conseguiram sobreviver a quase tudo - exceto, talvez, ao advento da internet.

p "Nos dias de hoje, uma mãe vai pedir a seu filho para baixar um formulário, preencha e envie pela internet, "admite Pinilla de Gomez.

p "Isso realmente estraga as coisas para nós."

p - Imagens de Luis Acosta. Vídeo de Juan Restrepo

p

Lavadeiras, seu comércio desaparecendo como sabão na água

p As mãos de Delia Veloz quase perderam as impressões digitais com o movimento rítmico constante de esfregar roupas sujas contra pedras ásperas em uma velha lavanderia pública em Quito.

p Com um esfregão de cachos cinza encaracolados, esta senhora de 74 anos é uma das poucas pessoas que restaram no Equador que ainda pratica o antigo e exigente trabalho de lavadeira - um ofício cada vez mais raro devido ao uso generalizado de máquinas de lavar domésticas.

p Wu Chi-kai dobra tubos de vidro polvilhados com pó fluorescente em forma sobre um poderoso queimador de gás

p Wu Chi-kai dobra tubos de vidro polvilhados com pó fluorescente em forma sobre um poderoso queimador de gás

p "Não gosto de máquinas de lavar, eles não lavam muito bem. Você pode esfregar as coisas melhor com a mão, “Veloz diz à AFP com orgulho enquanto derrama uma jarra de água gelada dos Andes sobre uma jaqueta.

p Há mais de cinco décadas ela trabalha na Ermita, uma lavanderia pública no centro colonial de Quito com sua pedra retangular, tanque de água e vários fios para pendurar coisas para secar.

p Para cada 12 artigos de vestuário, ela ganha $ 1,50 (1,20 euros) de seus poucos clientes - principalmente daqueles que não têm máquina de lavar ou preferem que as coisas sejam lavadas à mão.

p Em um bom dia, ela pode ganhar entre $ 3 e $ 6.

p Em Quito, ainda existem pelo menos cinco lavanderias públicas que foram construídas na primeira metade do século XX.

p Também há quem venha usar a roupa para lavar a própria roupa ou a de seu patrão - sem cobrança de taxa.

p E uma vez por mês, todos eles se reúnem para manter o local limpo e arrumado.

p - Imagens de Rodrigo Buendia

p O néon veio definir a paisagem urbana de Hong Kong, com enormes placas piscantes projetando-se horizontalmente das laterais dos edifícios

p O néon veio definir a paisagem urbana de Hong Kong, com enormes placas piscantes projetando-se horizontalmente das laterais dos edifícios

p

Waterboys começando a secar

p A falta de água encanada nos bairros mais pobres do Quênia tem, nos últimos 18 anos, significava uma vida para Samson Muli, vendedor de água na favela de Kibera, em Nairóbi.

p "Quando era criança, queria ser um homem de negócios, "diz o pai de dois filhos de 42 anos, que fornece água para açougueiros, peixarias e restaurantes no movimentado mercado Kenyatta.

p Vestido com uma sobrecapa parda, Muli usa uma mangueira para encher sua coleção de galões cilíndricos de 20 litros com água de três 10 independentes, Tanques de 000 litros. Ele carrega 15 de cada vez em um carrinho, e os transporta para seus clientes.

p The margins are tiny—Muli buys water at five shillings ($0.05) a can and sells for 15—but it can add up to 1, 000 shillings a day, enough to make a difference.

p "This job has changed my life because my children are able to go to school and I am able to afford to pay school fees for them, " ele diz.

p But Kenya's gradual development and the spreading provision of basic infrastructure, including piped water, means Muli's profitable days are numbered.

p — Pictures by Simon Maina. Video by Raphael Ambasu

p Chi-kai works without a safety visor and has been scalded and cut by glass which sometimes cracks and explodes

p Chi-kai works without a safety visor and has been scalded and cut by glass which sometimes cracks and explodes

p

Rickshaw pullers fade from India's streets

p Mohammad Maqbool Ansari puffs and sweats as he pulls his rickshaw through Kolkata's teeming streets, a veteran of a gruelling trade long outlawed in most parts of the world and slowly fading from India too.

p Kolkata is one of the last places on earth where pulled rickshaws still feature in daily life, but Ansari is among a dying breed still eking a living from this back-breaking labour.

p The 62-year-old has been pulling rickshaws for nearly four decades, hauling cargo and passengers by hand in drenching monsoon rains and stifling heat that envelops India's heaving eastern metropolis.

p Their numbers are declining as pulled rickshaws are relegated to history, usurped by tuk tuks, Kolkata's famous yellow taxis and modern conveniences like Uber.

p Ansari cannot imagine life for Kolkata's thousands of rickshaw-wallahs if the job ceased to exist.

p "If we don't do it, how will we survive? We can't read or write. We can't do any other work. Depois de começar, é isso. This is our life, " he tells AFP.

p Sweating profusely on a searing-hot day, his singlet soaked and face dripping, Ansari skilfully weaved his rickshaw through crowded markets and bumper to bumper traffic.

p Venezuelan darkroom technician Rodrigo Benavides refuses to go digital

p Venezuelan darkroom technician Rodrigo Benavides refuses to go digital

p Wearing simple shoes and a chequered sarong, the only real giveaway of his age is a long beard, snow white and frizzy, and a face weathered from a lifetime plying this trade.

p Twenty minutes later, he stops, wiping his face on a rag. The passenger offers him a glass of water—a rare blessing—and hands a bill over.

p "When it's hot, for a trip that costs 50 rupees ($0.75) I'll ask for an extra 10 rupees. Some will give, some don't, " ele diz.

p "But I'm happy with being a rickshaw puller. I'm able to feed myself and my family."

p — Pictures by Dibyangshu Sarkar. Video by Atish Patel

p

Hong Kong's neon nostalgia

p Neon sign maker Wu Chi-kai is one of the last remaining craftsmen of his kind in Hong Kong, a city where darkness never really falls thanks to the 24-hour glow of myriad lights.

p During his 30 years in the business, neon came to define the urban landscape, huge flashing signs protruding horizontally from the sides of buildings, advertising everything from restaurants to mahjong parlours.

p Although working with equipment and techniques that have virtually disappeared, he carries on as if digital photography does not exist

p Although working with equipment and techniques that have virtually disappeared, he carries on as if digital photography does not exist

p But with the growing popularity of brighter LED lights, seen as easier to maintain and more environmentally friendly, and government orders to remove some vintage signs deemed dangerous, the demand for specialists like Chi-kai has dimmed.

p Despite a waning client-base, the 50-year-old continues in the trade, working with glass tubes dusted inside with fluorescent powder and containing various gases including neon or argon, as well as mercury, to create different colours.

p He bends them into shape over a powerful gas burner at a scorching 1, 000 degrees Celsius.

p "Being able to twist straight glass materials into the shape I want, and later to make it glow—it's quite fun, "ele diz à AFP, though it is not without risks.

p Chi-kai works without a safety visor and has been scalded and cut by glass which sometimes cracks and explodes.

p "The painful experiences are the memorable ones, " he adds philosophically.

p His father used to scale Hong Kong's famous bamboo scaffolding while installing neon signs across the city.

p Believing the installation work too dangerous for his son, he instead encouraged him to learn to make the signs as a teenager. Chi-kai became one of only around 30 masters of the craft in Hong Kong, even in neon's heyday.

p Using his bathroom as a makeshift lab, he develops negatives, turning them into black and white prints

p Using his bathroom as a makeshift lab, he develops negatives, turning them into black and white prints

p Although demand is now significantly lower than at neon's peak in the 1980s, ele diz, there has been renewed interest and nostalgia for its gentler glow, immortalised in the atmospheric movies of award-winning Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai.

p Some of Chi-kai's clients are now requesting pieces for indoor decoration.

p "I've been working with neon lights all my life. I can't think of anything else I'd be better suited for, " ele diz.

p — Pictures by Philip Fong. Video by Diana Chan

p

Developing film as if digital didn't exist

p With an ancient 50-year-old Olympus camera and an enlarger that he bought in 1980, Venezuelan photographer Rodrigo Benavides works his "magic" inside a tiny improvised darkroom at home.

p Although working with equipment and techniques that have virtually disappeared, he carries on as if digital photography doesn't exist.

p "Doesn't interest me at all, " ele diz.

p Era uma vez, these clerks played an essential role—with public deeds, tax documents and contracts all passing through their hands

p Era uma vez, these clerks played an essential role—with public deeds, tax documents and contracts all passing through their hands

p Using his bathroom as a makeshift lab, he develops negatives, turning them into black and white prints. And it still fascinates him every time as the image slowly emerges on coming in to contact with the chemicals.

p "I have always tried to be economical with my resources, always have done, always will do, " ele diz, extolling the wonders of his Olympus 35 SP which uses a reel of film, doesn't need batteries and is completely manual.

p Born in Caracas 58 years ago, he still remembers the excitement when, at the age of 19, he bought the enlarger in London.

p And it was there that he became a keen follower of Group f/64, an influential movement of photographers who championed sharp-focused, unretouched images of natural subjects.

p He thinks technology has "upended" photography, turning it into a work of "fiction."

p "We have become desensitised to reality, which is much more interesting than fiction, " ele diz.

p Some 400 of his pictures taken over 30 years have been compiled into a book on the Venezuelan plains. Others are stacked up in his living room, forming a towering pile, some two meters high.

p "They are like my children, " says Benavides, who describes himself as a documentary photographer practising a trade on the verge of extinction.

-

p Delia Veloz, 74, is one of the few people left in Ecuador who still practises the ancient and demanding work of a washerwoman

p Delia Veloz, 74, is one of the few people left in Ecuador who still practises the ancient and demanding work of a washerwoman

-

p Washerwomen rub dirty clothes against rough stones at an old public laundry in Quito

p Washerwomen rub dirty clothes against rough stones at an old public laundry in Quito

-

p In Quito, there are still at least five public laundries which were built in the first half of the 20th century

p In Quito, there are still at least five public laundries which were built in the first half of the 20th century

-

p The lack of running water in Kenya's poorest neighbourhoods has meant a living for Samson Muli, a water seller in Nairobi's Kibera slum

p The lack of running water in Kenya's poorest neighbourhoods has meant a living for Samson Muli, a water seller in Nairobi's Kibera slum

-

p Waterboys supply water to butchers, fishmongers and restaurants in the crowded Kenyatta market

p Waterboys supply water to butchers, fishmongers and restaurants in the crowded Kenyatta market

-

p Kolkata is one of the last places on earth where pulled rickshaws still feature in daily life

p Kolkata is one of the last places on earth where pulled rickshaws still feature in daily life

-

p Mohammad Ashgar is one of the remaining Indian rickshaw pullers undertaking the gruelling trade

p Mohammad Ashgar is one of the remaining Indian rickshaw pullers undertaking the gruelling trade

p © 2018 AFP