p Ilustração de Parker Solar Probe se aproximando do sol. Crédito:NASA / Johns Hopkins APL / Steve Gribben

p Ilustração de Parker Solar Probe se aproximando do sol. Crédito:NASA / Johns Hopkins APL / Steve Gribben

p No cerne da compreensão de nosso ambiente espacial está o conhecimento de que as condições em todo o espaço - do sol às atmosferas dos planetas e ao ambiente de radiação no espaço profundo - estão conectadas. p Estudar essa conexão - um campo da ciência chamado heliofísica - é uma tarefa complexa:os pesquisadores rastreiam erupções repentinas de material, radiação, e partículas contra o pano de fundo do escoamento onipresente de material solar.

p Uma confluência de eventos no início de 2020 criou um laboratório baseado no espaço quase ideal, combinando o alinhamento de alguns dos melhores observatórios da humanidade, incluindo Parker Solar Probe, durante seu quarto sobrevoo solar - com um período de silêncio na atividade do sol, quando é mais fácil estudar essas condições de fundo. Essas condições forneceram uma oportunidade única para os cientistas examinarem como o sol influencia as condições em pontos por todo o espaço, com múltiplos ângulos de observação e a diferentes distâncias do sol.

p O sol é uma estrela ativa cujo campo magnético se espalha por todo o sistema solar, carregada pelo fluxo constante de material do sol, chamado de vento solar. Afeta naves espaciais e molda os ambientes dos mundos em todo o sistema solar. Observamos o sol, espaço perto da Terra e outros planetas, e até mesmo as bordas mais distantes da esfera de influência do sol por décadas. E 2018 marcou o lançamento de um novo, observatório revolucionário:Parker Solar Probe, com um plano de voar a cerca de 3,83 milhões de milhas da superfície visível do sol.

p Parker já teve quatro encontros imediatos com o sol. (Os dados dos primeiros encontros de Parker com o sol já revelaram uma nova imagem de sua atmosfera.) Durante seu quarto encontro solar, abrangendo partes de janeiro e fevereiro de 2020, a espaçonave passou diretamente entre o sol e a Terra. Isso deu aos cientistas uma oportunidade única:o vento solar que a Parker Solar Probe mediu quando estava mais próximo do sol iria, dias depois, chegar na Terra, onde o próprio vento e seus efeitos podem ser medidos tanto por espaçonaves quanto por observatórios terrestres. Além disso, observatórios solares na Terra e próximos a ela teriam uma visão clara dos locais no sol que produziram o vento solar medido pela Parker Solar Probe.

p "Sabemos pelos dados da Parker que existem certas estruturas originadas na superfície solar ou perto dela. Precisamos olhar para as regiões de origem dessas estruturas para entender completamente como elas se formam, evoluir, e contribuir para a dinâmica do plasma no vento solar, "disse Nour Raouafi, cientista do projeto para a missão Parker Solar Probe no Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory em Laurel, Maryland. "Observatórios baseados em terra e outras missões espaciais fornecem observações de apoio que podem ajudar a desenhar o quadro completo do que Parker está observando."

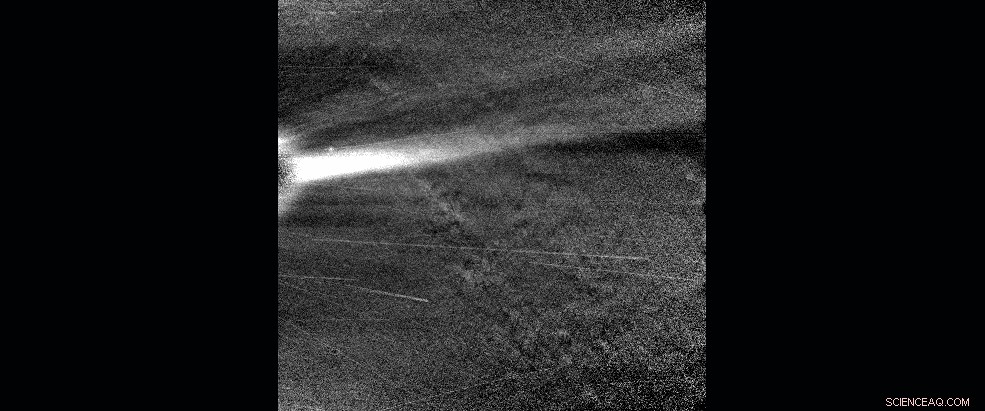

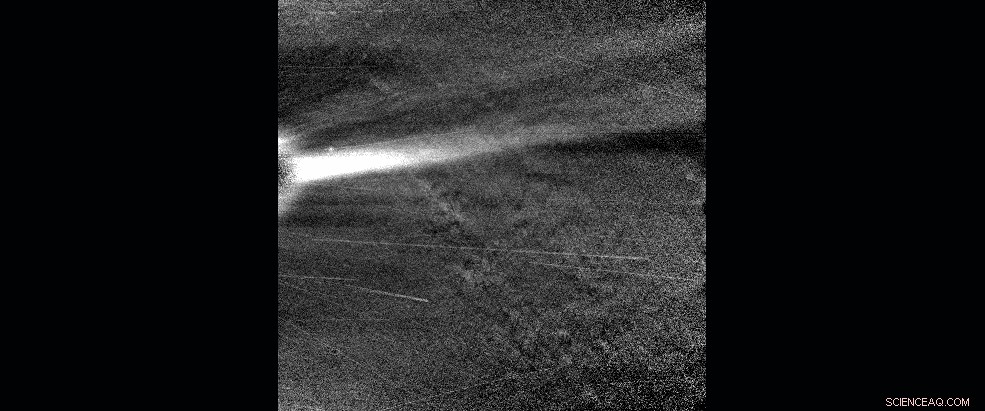

p Esta sequência animada de imagens de luz visível do instrumento WISPR da Parker Solar Probe mostra um streamer coronal, observado quando Parker Solar Probe estava perto do periélio em 28 de janeiro, 2020. Crédito:NASA / Johns Hopkins APL / Naval Research Lab / Parker Solar Probe

p Esta sequência animada de imagens de luz visível do instrumento WISPR da Parker Solar Probe mostra um streamer coronal, observado quando Parker Solar Probe estava perto do periélio em 28 de janeiro, 2020. Crédito:NASA / Johns Hopkins APL / Naval Research Lab / Parker Solar Probe

p Este alinhamento celestial seria de interesse dos cientistas em quaisquer circunstâncias, mas também coincidiu com outro período astronômico de interesse para os cientistas:o mínimo solar. Este é o ponto durante o regular do sol, ciclos de aproximadamente 11 anos de atividade quando a atividade solar está em seu nível mais baixo - erupções repentinas no sol, como erupções solares, ejeções de massa coronal e eventos de partículas energéticas são menos prováveis. E isso significa que estudar o Sol próximo ao mínimo solar é uma bênção para os cientistas que podem observar um sistema mais simples e, assim, desvendar quais eventos causam quais efeitos.

p "Este período oferece condições perfeitas para rastrear o vento solar do sol à Terra e aos planetas, "disse Giuliana de Toma, um cientista solar no High Altitude Observatory em Boulder, Colorado, que liderou a coordenação entre os observatórios para esta campanha de observação. “É um momento em que podemos seguir o vento solar com mais facilidade, já que não temos distúrbios do sol. "

p Por décadas, cientistas reuniram observações durante esses períodos de mínimo solar, um esforço co-liderado por Sarah Gibson, um cientista solar no High Altitude Observatory, e outros cientistas. Para cada um dos últimos três períodos solares mínimos, cientistas reuniram observações de uma lista cada vez maior de observatórios no espaço e no solo, esperando que a riqueza de dados sobre o vento solar não perturbado revele novas informações sobre como ele se forma e evolui. Para este período mínimo solar, os cientistas começaram a reunir observações coordenadas no início de 2019 sob o guarda-chuva Whole Heliosphere and Planetary Interactions, ou WHPI para breve.

p Esta campanha específica do WHPI compreendeu uma faixa mais ampla de observações:cobrindo não apenas o sol e os efeitos na Terra, mas também dados coletados em Marte e a natureza do espaço em todo o sistema solar - tudo em conjunto com o quarto e mais próximo sobrevoo do Sol de Parker Solar Probe.

p Os organizadores do WHPI reuniram observadores de todo o mundo - e além. Combinar dados de dezenas de observatórios na Terra e no espaço dá aos cientistas a chance de pintar o que pode ser a imagem mais abrangente de todos os tempos do vento solar:a partir de imagens de seu nascimento com telescópios solares, às amostras logo após deixar o sol com a Parker Solar Probe, para observações multiponto de seu estado de mudança em todo o espaço.

p Continue lendo para ver exemplos dos tipos de dados capturados durante esta colaboração internacional de observatórios do sol e do espaço.

p Dados do Observatório Solar Mauna Loa, no Havaí, mostram um jato de material sendo ejetado próximo ao pólo sul do Sol em 21 de janeiro 2020 (UTC). Esta imagem de diferença é criada subtraindo os pixels da imagem anterior da imagem atual para destacar as alterações. Crédito:Observatório Solar Mauna Loa / K-Cor

p Dados do Observatório Solar Mauna Loa, no Havaí, mostram um jato de material sendo ejetado próximo ao pólo sul do Sol em 21 de janeiro 2020 (UTC). Esta imagem de diferença é criada subtraindo os pixels da imagem anterior da imagem atual para destacar as alterações. Crédito:Observatório Solar Mauna Loa / K-Cor

p

Parker Solar Probe

p Os primeiros dados da passagem próxima da Parker Solar Probe pelo sol durante a campanha WHPI mostram um sistema de vento solar mais dinâmico do que o que é visível em observações perto da Terra. Em particular, os cientistas esperam que o conjunto completo de dados - baixado para a Terra em maio de 2020 - revele estruturas dinâmicas, como pequenas ejeções de massa coronal e cordas de fluxo magnético em seus estágios iniciais de desenvolvimento, que não pode ser visto com outros observatórios assistindo de mais longe. Conectando estruturas como esta, anteriormente muito pequeno ou muito distante para ver, com o vento solar e as medições próximas à Terra podem ajudar os cientistas a entender melhor como o vento solar muda ao longo de sua vida e como suas origens perto do sol afetam seu comportamento em todo o sistema solar.

p

Observatório Solar Mauna Loa

p As vistas de close-up da Parker Solar Probe de estruturas eólicas solares são complementadas por observatórios solares na Terra e no espaço, que possuem um campo de visão maior para captar estruturas eólicas solares.

p Dados do Observatório Solar Mauna Loa, no Havaí, mostram um jato de material sendo ejetado próximo ao pólo sul do Sol em 21 de janeiro 2020. Jatos coronais como este são uma característica do vento solar que os cientistas esperam observar mais de perto com a Parker Solar Probe, já que os mecanismos que os criam podem lançar mais luz sobre o nascimento e a aceleração do vento solar.

p "Seria extremamente feliz se a Parker Solar Probe observasse este jato, uma vez que forneceria informações sobre o plasma e o campo dentro e ao redor do jato não muito depois de sua formação, "disse Joan Burkepile, cientista-chefe do instrumento K-coronógrafo do Observatório de Magnetismo Solar Coronal no Observatório Solar de Mauna Loa, que capturou essas imagens.

Observatório de Relações Solar e Terrestre da NASA, ou ESTÉREO, tirou imagens extras com tempos de exposição mais longos para melhorar a visualização da estrutura ao vento solar. Essas imagens de diferença, de 21 a 23 de janeiro, 2020, são criados subtraindo os pixels de uma imagem anterior da imagem atual para destacar as alterações. Crédito:NASA / STEREO p

Observatório de Relações Solar e Terrestre

p Junto com as observações do vento solar da Parker Solar Probe e perto da Terra, scientists also have detailed images of the sun and its atmosphere from spacecraft like NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory and the Solar and Terrestrial Relations Observatory. NASA's Solar and Terrestrial Relations Observatory, or STEREO, has a distinct view of the sun from its vantage point about 78 degrees away from Earth.

p During this WHPI campaign, scientists took advantage of this unique viewing angle. From Jan. 21-23—when Parker Solar Probe and STEREO were aligned—the STEREO mission team increased the exposure length and frequency of images taken by its coronagraph, revealing fine structures in the solar wind as they speed out from the sun.

p These difference images are created by subtracting the pixels of a previous image from the current image to highlight changes—here, revealing a small CME that would otherwise be difficult to see.

p The Solar Dynamics Observatory, ou SDO, takes high-resolution views of the entire sun, revealing fine details on the solar surface and the lower solar atmosphere. These images were captured in a wavelength of extreme ultraviolet light at 171 Angstroms, highlighting the quiet parts of the sun's outer atmosphere, the corona. This data—along with SDO's images in other wavelengths—maps much of the sun's activity, allowing scientists to connect solar wind measurements from Parker Solar Probe and other spacecraft with their possible origins on the sun.

p

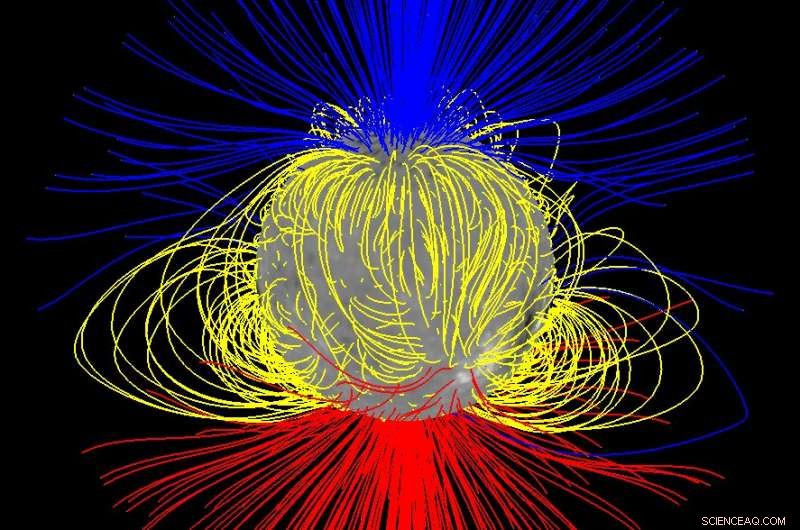

Modeling the Data

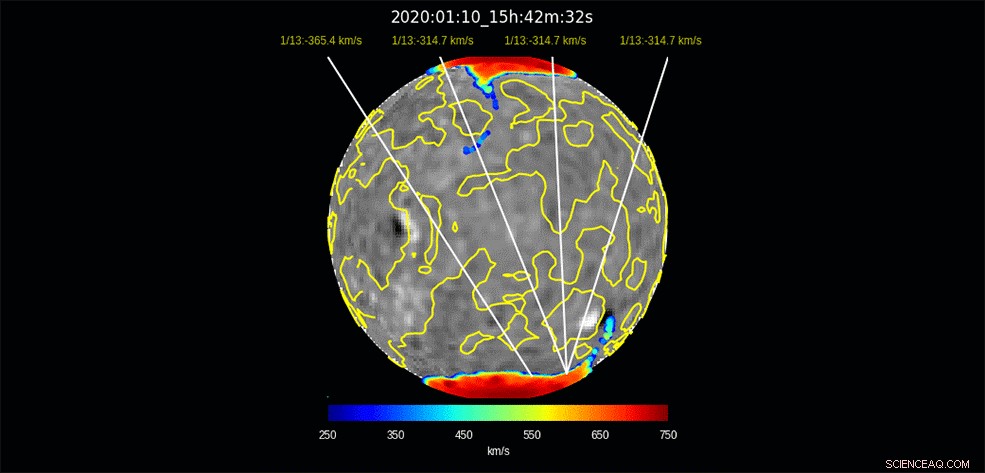

NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory keeps a constant eye on the Sun. Essas imagens, captured in a wavelength of extreme ultraviolet light, span Jan. 15 – Feb. 11, 2020. Credit:NASA/SDO p Idealmente, scientists could use these images to readily pinpoint the region on the sun that produced a particular stream of solar wind measured by Parker Solar Probe—but identifying the source of any given solar wind stream observed by a spacecraft is not simple. Em geral, the magnetic field lines that guide the solar wind's movement flow out of the Northern half of the sun point in the opposite direction than they do in the Southern half. In early 2020, Parker Solar Probe's position was right at the boundary between the two—an area known as the heliospheric current sheet.

p "For this perihelion, Parker Solar Probe was very close to the current sheet, so a little nudge one way or the other would make the magnetic footpoint shift to the south or north pole, " said Nick Arge, a solar scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. "We were on the tipping point where sometimes it went north, sometimes south."

p Predicting which side of the tipping point Parker Solar Probe was on was the responsibility of the modeling teams. Using what we know about the sun's magnetic field and the clues we can glean from distant images of the sun, they made day-by-day predictions of where, precisely, on the sun birthed the solar wind that Parker would fly through on a given day. Several modeling groups made daily attempts to answer just that question.

p Using measurements of the magnetic field at the sun's surface, each group made a daily prediction for the source region producing the solar wind that Parker Solar Probe was flying through.

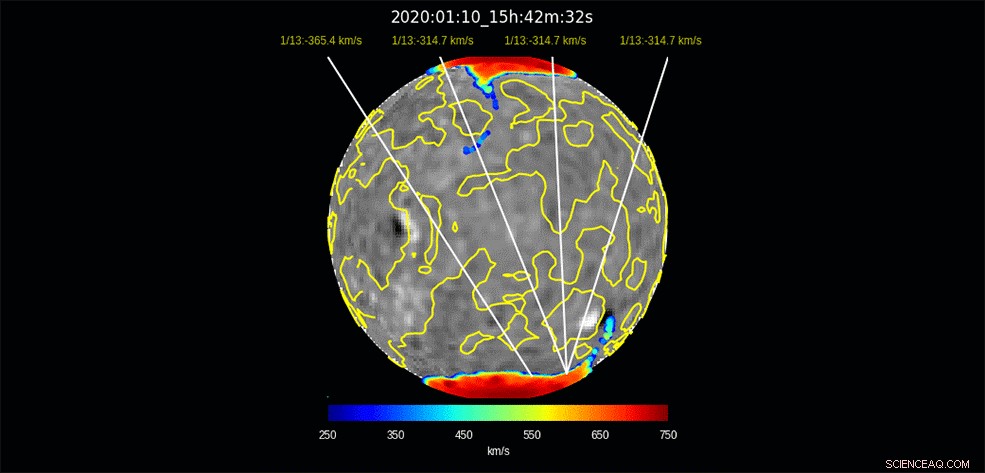

p Arge worked with Shaela Jones, a solar scientist at NASA Goddard who did daily forecasting during the WHPI campaign, using a model originally developed by Arge and colleagues Yi-Ming Wang and Neil Sheeley, called the WSA model. According to their forecasts, the predicted source of the solar wind switched between hemispheres suddenly during the observation campaign, because Earth's orbit at the time was also closely aligned with the heliospheric current sheet—that region where the direction of magnetic polarity and the source of the solar wind switches between north and south. They predicted that Parker Solar Probe, flying in a similar plane as Earth, would experience similar switches in solar wind source and magnetic polarity as it flew near the sun.

p Solar wind models rely on daily measurements of the sun's surface magnetic field—the black and white image underlaid. This particular model used measurements from the National Solar Observatory's Global Oscillation Network Group and a model that focuses on predicting how the sun's surface magnetic field will change over several days. Creating these magnetic surface maps is a complicated and imperfect process unto itself, and some of the modeling groups participating in the WHPI campaign also used magnetic measurements from multiple observatories. This, along with differences in each group's models, created a spread of predictions that sometimes placed the source of Parker Solar Probe's solar wind stream in two different hemispheres of the sun. But given the inherent uncertainty in modeling the solar wind's source, these different predictions can actually make for more robust operations.

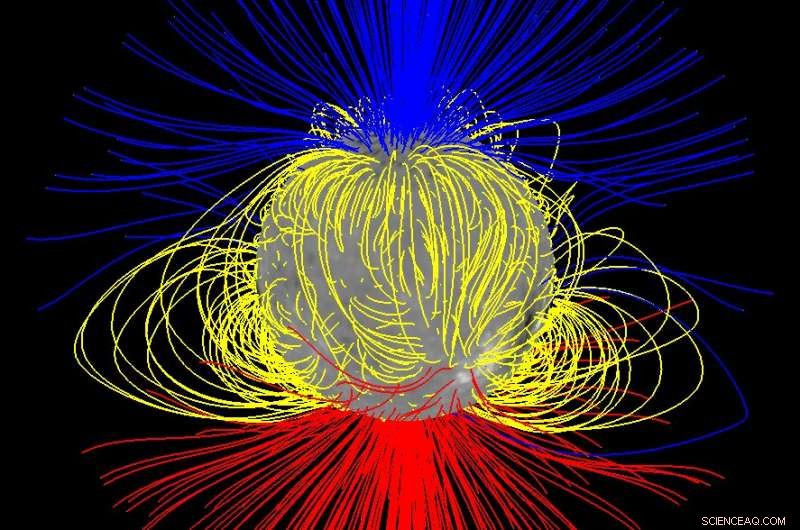

p The sun's "open" magnetic field — shown in this model in blue and red, with looped or closed field shown in yellow — primarily comes from near the Sun's north and south poles during solar minimum, but it spreads out to fill space converging near the Sun's equator. Credit:NASA/Nick Arge

p The sun's "open" magnetic field — shown in this model in blue and red, with looped or closed field shown in yellow — primarily comes from near the Sun's north and south poles during solar minimum, but it spreads out to fill space converging near the Sun's equator. Credit:NASA/Nick Arge

p "If you can observe the sun in two different places with two telescopes, you have a better chance to get the right spot, "disse Jones.

p

Poker Flat Incoherent Scatter Radar

p The solar wind carries with it both an enormous amount of energy and the embedded magnetic field of the sun. When it reaches Earth, it can ring our planet's natural magnetic field like a bell, making it bend and deform—which produces a measurable change in magnetic field strength at certain points on Earth's surface. We track those changes because magnetic field oscillations can lead to a host of space weather effects that interfere with spacecraft or even, occasionally, utility grids on the ground.

p A host of ground-based magnetometers have tracked these effects since the 1850s, and they're one of the many sets of data scientists are gathering in connection with this campaign. Other ground-based instruments can reveal the invisible effects of space weather in our atmosphere. One such system is the Poker Flat Incoherent Scatter Radar, or PFISR—a radar system based at the Poker Flat Research Range near Fairbanks, Alaska.

p This radar is specially tuned to detect one of most reliable indicators of a disturbance in Earth's magnetic field:electrons in Earth's upper atmosphere. These electrons are created when particles trapped in the magnetosphere are sent zooming into Earth's atmosphere by a complex series of events, a set of circumstances known as a magnetospheric substorm.

p On Jan. 16, PFISR measured the changing electrons in Earth's upper atmosphere during one such substorm. During a substorm, particles cascade into the upper atmosphere, not only creating the shower of electrons measured by the radar, but driving a more visible effect:the aurora. PFISR uses multiple beams of radar oriented in different directions, which allowed scientists to build up a three-dimensional picture of how electrons in the atmosphere changed throughout the substorm.

p This model run — produced by Nick Arge and Shaela Jones using the WSA model — illustrates the predicted origin for solar wind that will impact Earth days later, spanning Jan. 10 – Feb. 3, 2020. The colored regions near the sun's north and south poles show the regions from which the solar wind flows out, with red regions showing a faster flow and blue regions showing a slower flow. The yellow lines on the sun divide areas of opposite magnetic polarity. The white lines indicate the predicted points of origin for the solar wind arriving at Earth at the given date. The black and white underlaid image shows a map of the magnetic field at the sun's surface, the basis for the model's predictions. The black regions are where the magnetic field points inward, toward the sun, and white regions are where the field points outward, away from the sun. Credit:NASA/Nick Arge/Shaela Jones

p This model run — produced by Nick Arge and Shaela Jones using the WSA model — illustrates the predicted origin for solar wind that will impact Earth days later, spanning Jan. 10 – Feb. 3, 2020. The colored regions near the sun's north and south poles show the regions from which the solar wind flows out, with red regions showing a faster flow and blue regions showing a slower flow. The yellow lines on the sun divide areas of opposite magnetic polarity. The white lines indicate the predicted points of origin for the solar wind arriving at Earth at the given date. The black and white underlaid image shows a map of the magnetic field at the sun's surface, the basis for the model's predictions. The black regions are where the magnetic field points inward, toward the sun, and white regions are where the field points outward, away from the sun. Credit:NASA/Nick Arge/Shaela Jones

p Because this substorm took place so early in the observation campaign—only one day after data collection began—it's unlikely that it was caused by conditions on the sun observed during the campaign. Mas mesmo assim, the connection between magnetospheric substorms and the broader, global-scale effects created by the solar wind—called geomagnetic storms—isn't entirely understood.

p "This substorm didn't happen during a geomagnetic storm time, " said Roger Varney, principal investigator for PFISR at SRI International in Menlo Park, Califórnia. "The solar wind during this event is fluctuating, but not particularly strongly—it's basically background noise. But solar wind is basically never steady; it's constantly putting some energy into the magnetosphere."

p This deposit of energy into Earth's magnetic system has far-reaching effects:for one, changes in the composition and density of Earth's upper atmosphere can garble communications and navigation signals, an effect often characterized by total electron content. Changes in density can also affect the orbits of satellites to great degree, introducing uncertainty about precise position.

p

MAVEN

p Earth isn't the only planet where the solar wind has measurable effects—and studying other worlds in our solar system can help scientists understand some of the solar wind's effects on Earth and how it influenced the evolution of Earth and other worlds throughout the solar system's history.

p At Mars, the solar wind coupled with Mars' lack of a global magnetic field may be a major factor in the dry, barren world the Red Planet is today. Though Mars was once much like Earth—warm, with liquid water and a thick atmosphere—the planet has changed drastically over the course of its four-billion-year history, with most of its atmosphere being stripped away to space. With similar processes observed here on Earth, scientists leverage understanding of solar-planetary interactions at Mars to determine how processes leading to atmospheric escape has the ability to change whether a planet is habitable or not. Hoje, the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution mission, or MAVEN, studies these processes at Mars. MAVEN observations at Mars are available for this latest WHPI campaign.

The Poker Flat Incoherent Scatter Radar in Poker Flat, Alasca, makes 3-D measurements of electrons in Earth's upper atmosphere. These electrons are produced by the same process that produces aurora, seen here by the Poker Flat All-Sky Camera, which images aurora over Alaska, on Jan. 16, 2020. Credit:Poker Flat Incoherent Scatter Radar (NSF)/Poker Flat All-Sky Camera (University of Alaska Fairbanks)/Don Hampton p Over the coming months, heliophysicists around the world will begin to study data from these observatories in depth, hoping to draw connections that reveal new knowledge about the sun and its changes that influence Earth and space across the solar system.

p Parker Solar Probe is part of the NASA Heliophysics Living with a Star program to explore aspects of the sun-Earth system that directly affect life and society. O programa Living with a Star é administrado pelo Goddard Space Flight Center da agência em Greenbelt, Maryland, para o Diretório de Missões Científicas da NASA em Washington. The Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, projetado, built and operates the spacecraft and manages the mission for NASA.